He Wanted the Moon (20 page)

Read He Wanted the Moon Online

Authors: Mimi Baird,Eve Claxton

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Psychology, #Psychopathology, #Bipolar Disorder, #Medical

Three years later I graduated from Colby-Sawyer College. I went to work in Cambridge as a secretary at the dean’s office of the Harvard Graduate School of Education. This was a happy time for me—I enjoyed my job and newfound independence, sharing an apartment on Marlborough Street with three girlfriends. Various friends were beginning to pair off and get married, and I knew that soon I would do the same. There was a feeling for all of us that life was just beginning.

Then, in May 1959, a year after my college graduation, I received a telephone call from my mother.

“Your father has died,” she informed me, without preamble. “You are to travel to Texas for the funeral right away.”

Stunned by her announcement, I did as I was told. I hung up the telephone and began my preparations, grabbing clothing from hangers and packing various items in my suitcase. I sensed that this activity would be easier than trying to comprehend the loss of a father I had always missed—but who now was truly gone—and whose funeral I had just been inexplicably commanded to attend.

The following day, my sister, who was still in college, met me at Logan Airport and we flew to Dallas together. We spent the duration of the flight in uncomprehending silence. My mother’s aunt, our great-aunt Martha, who lived in Dallas, met us at the airport and took us to her apartment. The next morning, we drove to church to attend our father’s funeral.

His obituary appeared that week in the local newspaper, although I didn’t see it until many years later:

Dr. Perry C. Baird Funeral Rites Slated Thursday

Funeral services for Dr. Perry Cossart Baird Jr., 55, a Dallas native and at one time an internationally known dermatologist, will be held at 11:30 a.m. Thursday.

Dr. Baird died Monday in a Detroit, Mich. hotel. He moved to Detroit six weeks ago to enter business.

He attended Dallas public schools and Southern Methodist University, and graduated from the University of Texas with honors, including Phi Beta Kappa. He later attended Harvard Medical School, graduating with the highest honors ever awarded a graduate at that time.

In addition to his private practice he served on the staff of Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston, Mass., and as dermatologist consultant and teacher at Harvard. He lived in Boston about 20 years. Persons throughout the world consulted him during his years in Boston.

Dr. Baird returned to Dallas about 10 years ago after his retirement. He was a member of numerous service and private clubs in Boston.

Survivors are two daughters, Miss Mimi Baird and Miss Catherine Baird, both of Boston, Mass.; two brothers, James G. Baird of Minden, La., and Lewis P. Baird of Dallas; one sister, Mrs. W. O. Williamson Jr. of Atlanta, Ga.; and his mother, Mrs. Perry C. Baird of Dallas.

The funeral service was held at a small chapel, but I have few other memories of our two days in Dallas, except that, despite the sad occasion, our Texan relatives were overjoyed to see us. We had been estranged from our father’s family since the divorce fifteen years ago and over the next few days, we spent our time continually being introduced to relatives that we didn’t know. Despite our bewilderment, my grandparents and aunts and uncles treated us with unguarded love and enthusiasm. Everywhere we went people gathered around us and photographs were taken.

By then, my grandmother—who was known to all as Momma B.—was frail and elderly, but she was particularly delighted to see us, repeatedly wrapping us in hugs. The reunion evidently meant a great deal to her, and I wish I’d had the maturity at the time to understand the reason. Perry had been her dearest son, and the appearance of her long-lost granddaughters at his funeral must have been a source of much consolation. This could have been the beginning of a new relationship with our grandmother, but in fact, it was the last time we saw her. Three months after my father’s passing, she followed him, dying brokenhearted.

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

After the funeral, my sister and I flew back to Boston. The following day, I returned to my usual routine, and my sister resumed her studies. In the ensuing weeks, I put away the confusing matter of our father’s death, diverting my attentions to my job and social life.

Soon after, I became engaged. It was 1960, and my ambitions were those of so many young women at that time: I wanted to be a wife; I wanted to have a family.

A few weeks before my wedding day, my mother took me to one side.

“You don’t need to worry,” she informed me. “Your father’s trouble can’t be inherited. Your children will be fine.”

I stared at her in disbelief. It had never occurred to me that my father’s illness might be inherited. I had no understanding of manic depression—it had never been talked about or adequately explained to me. I certainly never thought to look it up in a medical dictionary; the subject was completely taboo.

“Thank you, mother,” I responded. End of conversation.

After my son and my daughter were born, in 1961 and 1963, I put my focus squarely on my children. I absorbed myself in their daily development, delighting in the milestones along the way. It was only when I emerged from their early childhood years that the mystery of my father began to trouble me again. I knew I had been given incomplete information about my family history and therefore, on some level, I felt myself to be incomplete. What had taken place all those years ago in the house on Clovelly Road? Where had my father gone and why had we never visited him? Surely my mother wouldn’t deny me some basic information at this point. I was an adult now, with children of my own.

But it wasn’t until the fall of 1969 that I got up the courage to call her, letting her know that I had things on my mind and that I wanted to visit to talk about my father. I made a special trip to Woodstock, Vermont, to the country home she shared with my stepfather. My mother was in her late fifties by then, and strands of gray were starting to appear in her hair, but she still found it hard to sit and listen, preferring to be in constant, nervous motion. The afternoon of my arrival, we went to sit in the outdoor porch, with its beautiful views of Mount Ascutney. The autumn air was chilled.

“Mother, I would like to ask you some questions about my father.”

Instinctively she looked around at the screen door that led to the living room, trying to ascertain if my stepfather was within earshot.

“What happened after he left us?”

“Your father was ill,” she replied, using those same words she had always rolled out. “He had manic-depressive psychosis.”

“I know. But didn’t you ever visit him? Where was he?”

“Your father was … hard to see,” she replied, slowly.

I could see my stepfather peering through the screen door to the porch, straining his neck for a better view. My mother was shuffling in her seat, as if she couldn’t wait for the interrogation to be over.

“What did his doctors say about him?” I asked.

“Really,” she said impatiently. “I don’t remember.”

Meanwhile, my stepfather appeared on the opposite side of the porch, beginning—rather unconvincingly—to rearrange the wood stacks piled up near the outdoor fireplace. I marveled at his determination to interrupt our conversation; nonetheless, I was resolved to continue.

“Mother, did you ever consider taking me to see him?”

“Maybe I did,” she replied. “It was so long ago. I don’t know how you expect me to remember.”

“I think it’s only fair that I should know.”

My stepfather turned around from the other side of the porch.

“Gretta,” he called, “it’s growing cold out here. I think you should come inside.”

That was the end of it. My mother went inside and the conversation was closed.

My mother’s reticence wasn’t only due to stubbornness; in fact, it had deep roots in her own childhood. Not only had she married a man with manic depression, my mother had been born to a father with the exact same illness.

I must have been in high school when she happened to mention, in her offhand way, that her father, Henry Gibbons, had also suffered with manic depression.

“I was ten years old when he went away,” she told me. “He spent the rest of his life in a hospital in Norristown, Pennsylvania.”

Growing up, I had always been informed that my grandfather was deceased and that my grandmother was a widow. No one spoke of him. The family simply behaved as if he didn’t exist. Only later did I learn from my mother that—for most of my childhood—my grandfather Henry had been very much alive and locked away in a psychiatric institution.

In other words, my mother and I had an extraordinary bond, however unspoken. We had both lost our fathers to mental illness. This might have brought us closer together. Instead, the opposite was true. My mother’s refusal to talk about what had happened to my father was a direct echo of the events of her own childhood. Her father, Henry, had been hidden away; therefore my father’s circumstances must also be hidden. This was simply the way things were done. Silence was an inheritance.

Even so, as the years went on, I still held out hope that I would be able to open the lines of communication with my mother. Every now and again, I would make another overture, to no avail. My sister, meanwhile, followed my mother’s lead. Catherine had little interest in talking about the past. She had been a toddler when our father was taken away. As far as she was concerned, he had simply never featured in her life, and that was that.

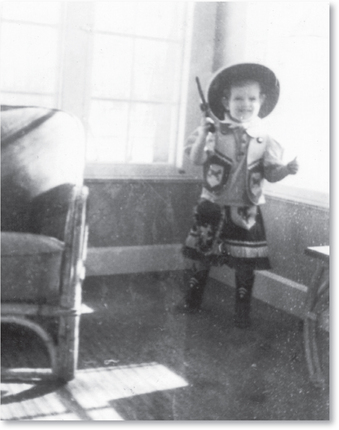

It was different for me. I could remember being with my father at his doctor’s offices on Commonwealth Avenue, the familiar scent of sterile instruments in the air. I could recall him proudly taking a photograph of me wearing a cowgirl outfit that my grandmother had given me for my birthday. In another memory, I could remember looking for my father, going upstairs to the little bathroom adjacent to my parents’ bedroom to find him stepping out of the shower, wrapping a towel around his middle. To me, he seemed as tall as the giants in my fairytale book. My memories of my father’s presence came back to me in bright flashes.