Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh (32 page)

Read Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh Online

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #World, #Ancient

Gebel Silsila, forty miles to the north of Aswan, was both the location of sandstone quarries and a cult centre for the worship of the Nile in flood. Senenmut's shrine, which is of uncertain use and which has been variously described as a grotto, cenotaph, temple and tomb, is one of a number of such edifices built on the West Bank by the highest-ranking civil servants of the 18th Dynasty, including Hapuseneb, the first Prophet of Amen and architect of Hatchepsut's burial chamber, and Neshi, the leader of Hatchepsut's celebrated expedition to Punt. The monument therefore serves to emphasize Senenmut's prominent role amongst the great and the good (and the influential) of his time.

Senenmut's shrine (Shrine 16) is situated high on the cliff and faces east, towards the Nile. It was almost certainly designed to be reached from the river at the time of high water. The shrine consists of a framed doorway, cut into the sandstone cliff, leading into a square room housing a seated statue of Senenmut, cut from the living rock. The walls originally displayed a series of sunk relief scenes and inscriptions. These are now badly damaged, although the flat ceiling still shows traces of its original colourful pattern. Although most of the Gebel Silsila shrines incorporate a fairly consistent funerary emphasis in their texts and scenes, Senenmut'S shrine omits the customary earthly and funerary feasts and includes instead a depiction of Hatchepsut being embraced by the crocodile-headed god Sobek and Nekhbet, the vulture goddess of Upper Egypt, shown as a woman wearing a feathered vulture headdress. As other commentators have observed, ‘the peculiar status of Senenmut and the relationship between him and his monarch no doubt account for these unusual features’.

6

… I was promoted before the companions, knowing that I was distinguished with her; they set me to be chief of her house, the palace, may it live, be prosperous and be healthy, being under my supervision, being judge in the whole land, Overseer of the Granaries of Amen, Senenmut…

7

Following Hatchepsut's rise to power, Senenmut dropped a number of his lesser titles, including that of tutor to Neferure, acquired a clutch of more prestigious accolades (such as Overseer of the Granaries of Amen and Overseer of all the Works of the King [Hatchepsut] at Karnak), and settled into his principal post as Steward of Amen. Although, as far as we are aware, he never held the title of First Prophet of Amen, arguably the most powerful position that a non-royal Egyptian could aspire to, the stereotypical and self-congratulatory propaganda text quoted above confirms the wide range of his official duties. Titles in ancient Egypt were not necessarily indicative of actual employment, but rather served to place a man in the social hierarchy; for example, the exact duties of the ‘Sandal-bearer of the King’ or the ‘Royal Washerman’ are unknown, but it is highly unlikely that they involved the performance of undignified personal services for the monarch, as both posts were held by men of rank and breeding. Winlock's intriguing suggestion that, in addition to his obvious public duties, Senenmut had ‘held more intimate ones like those of the great nobles of France who were honoured in being allowed to assist in the most intimate details of the royal toilet at the king's levees’

8

appears very unlikely. Winlock based this remarkable conclusion on the fact that Senenmut bore what we now assume to be the purely honorary titles of ‘Superintendent of the Private Apartments’, ‘Superintendent of the Bathroom’, and ‘Superintendent of the Royal Bedroom’.

Senenmut's plethora of epithets should, therefore, be taken as an indication of his general importance rather than a precise listing of his actual duties, and the exact amount of time that he was actually required to devote to his official posts remains unclear. His range of titles does, however, suggest that he might by now have been a relatively elderly man. As the average life expectancy for a high-ranking court official was between thirty and forty-five years, any official who lived past forty years could reasonably expect to become a much venerated and much decorated elder statesman, if only because death had removed almost all his contemporary competitors. The longer that Senenmut lived, and of course the longer that he continued in the queen's favour, the more titles he could expect to acquire. Thus we find Ineni, an equally long-serving statesman, rejoicing in the titles of:

Hereditary Prince, Count, Chief of all Works in Karnak; the double silver-house was in his charge; the double gold house was on his seal; Sealer of all contracts in the House of Amen; Excellency, Overseer of the Double Granary of Amen.

9

Unofficially, Senenmut seems to have acted as the queen's right-hand-man and general factotum. The rapid increase in his personal wealth at this time is obvious. Not only was Senenmut now rich enough to bury his mother with appropriate pomp, he was also able to start constructing his own magnificent tomb, acquire a quartzite sarcophagus and build his Silsila shrine.

In the absence of any contemporary written description of Senenmut, we must turn to his surviving images in an attempt to find clues to his character. What did the queen see when she turned to look at her faithful servant? Possibly not what modern observers have seen when studying Senenmut's somewhat unprepossessing physiognomy:

Whatever first attracted Great Royal Wife Hatchepsut to Senenmut, it certainly was not his good looks…. portraits show a pinch-featured man with a pointed high-bridge nose and fleshy lips that seem pursed; with a weak chin tending to jowliness and eyes that might be judged a bit shifty; and with deep creases or wrinkles about the cheeks, nose and mouth, and under the jaw.

10

Winlock was also struck by Senenmut's ‘aquiline nose and nervously expressive, wrinkled face. As for the wrinkles, they surely were the feature by which Senmut was known’.

11

However beauty, or in this case a shifty eye, wrinkles and a tendency towards ‘jowliness’, lies as always in the eye of the beholder, and others have been prepared to take a kinder view of his features:

The profile has the imperious outline of the Tuthmoside family. A slight fullness of the throat, with two strokes of the brush suggesting folds, the sparingly executed lines around the eyes, and a reversed curve from the eyes past nose and mouth indicate in masterful fashion the sagging plump features of the aging man of affairs.

12

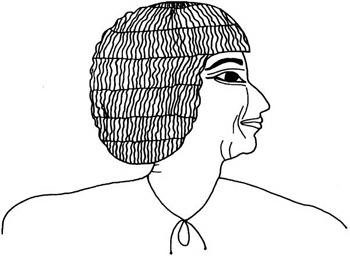

Each of these descriptions has been based on our four surviving ink sketches of Senenmut's face. Three of these portraits are on ostraca now

housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, while the fourth has survived undamaged on the wall of Tomb 353. All four show Senenmut in profile, with a single eye and eyebrow facing forwards in the conventional Egyptian style. His rather rounded face and double chin certainly suggest a man used to enjoying the finer things in life, while his crows’ feet and wrinkles confirm that he was no longer in the first flush of youth when the sketches were made. The striking similarity between these less-than-flattering sketches suggests that all four may be actual depictions of Senenmut, drawn by people who actually knew him. In contrast, our other more formal images of Senenmut, his statues and his tomb illustrations, are merely conventional representations of a ‘great Egyptian man’ with little or no attempt at accurate portrayal.

… Grant that there may be… made for me many statues from every kind of precious hard stone for the temple of Amen at Karnak and for every place wherein the majesty of this god proceeds…

13

At least twenty-five hard stone statues of Senenmut have survived the ravages of time. This is an extraordinarily large number of statues for a

Fig. 7.2 Sketch-portrait of Senenmut from the wall of Tomb 353

private individual; no other New Kingdom official has left us so many clear indications of his exalted rank and, as we must assume that most, if not all, were the gift of the queen, his highly favoured status. In ancient Egypt, statues were not simply designed to be

objets d'art

, intended to enhance rooms or beautify gardens. All images were automatically invested with magical or religious powers, and they were commissioned so that they could replace either living people or gods within the temple and the tomb. It seems likely, given his links with Amen, that the majority of Senenmut's statues would have been placed in the courtyard of the great temple of Amen at Karnak, although Senenmut appears to have dedicated statues of himself in most of the major temples around Thebes. Within the temple the statues would have been positioned in ranks facing the sanctuary, ensuring that the living Senenmut received the benefits of their proximity to the god.

The artistic inventiveness of the Senenmut figures confirms the innovative nature and general technical excellence of small-scale sculpture throughout Hatchepsut's reign. They depict Senenmut in his various roles, most typically holding the infant Neferure in his arms, a pose designed to stress Senenmut's importance rather than his tender feelings towards his young charge. Some show him squatting with the child's body wrapped in, and almost obscured by, his cloak, while one shows Senenmut sitting with Neferure – stiff and unchild-like – held at right angles in his lap, a position hitherto reserved for women nursing children. The majority of the remaining statues show Senenmut kneeling to present a religious symbol such as a sistrum or a shrine. At least one statue, a 1.55 m (5 ft 1 in) high granite representation of Senenmut presenting a sistrum to the goddess Mut, originally housed in the temple of Mut at Karnak, was so admired by its subject that it was reproduced in black diorite on a smaller scale, presumably so that it could be placed in a less public shrine and used for private worship.

Not all contemporary representations of Senenmut were intended to flatter, as crude graffiti from an unfinished Middle Kingdom tomb show. This chamber, situated in the cliffs above Deir el-Bahri, was used as a resting place by the gangs of workmen engaged in building Hatchepsut's mortuary temple. Here the builders idled away their rest breaks

by doodling and scribbling on the walls. Included amongst the doodles are a number of mildly pornographic scenes including depictions of naked, well-endowed young men. One sketch shows a tall, fully clothed, unnamed male who has variously been identified as both Senenmut and Hatchepsut, and who is apparently being approached by a smaller naked male with an improbably large erection. Although it is possible that the two figures represent entirely separate and unconnected doodles, they are close enough together for us to speculate whether Senenmut/Hatchepsut is about to become the subject of a homosexual encounter.

Homosexual intercourse for pleasure in ancient Egypt is not well attested. Instead, homosexuality was generally regarded as a means of gaining revenge on a defeated enemy. By implanting his semen the aggressor not only humiliated his victim by forcing him to take the part of a woman, but also gained a degree of power over him. If Senenmut is really being approached in this way, he is about to be thoroughly degraded. No disgrace ever attached to the aggressor performing the homosexual rape; the shame belonged entirely to the victim. Thus, in the New Kingdom story which tells of the seduction of the young god Horus by his uncle Seth, it is Horus who feels the shame of a woman. Seth is merely acting like any red-blooded male:

Now when evening had come a bed was prepared for them and they lay down together. At night Seth let his member become stiff, and he inserted it between the thighs of Horus. And Horus placed his hand between his thighs, and caught the semen of Seth.

14

By catching the semen before it enters his body and subsequently throwing it into the marsh, Horus has effectively thwarted his uncle's evil plan to discredit him in the eyes of other males. Later, with the help of his mother, he is able to turn the tables on Seth. He sprinkles his own semen over the lettuces growing in the palace garden which he knows that Seth will eat. When the two gods are called to give an account of their deeds, although Seth claims to have done ‘a man's deed’ to Horus, the semen of Horus is discovered within Seth's own body and Seth is totally humiliated.

Nearby on the tomb wall (

Fig. 7.3

) are shown a couple, naked but for their idiosyncratic headgear, who are indulging in a form of sexual