Hacking Politics: How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists, and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet (24 page)

Authors: and David Moon Patrick Ruffini David Segal

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: POL035000

I forced my CompSci Phd roommate to spend a Saturday and Sunday cobbling together a slapdash site to which we appended a call-to-arms video that we’d filmed with Wyden earlier that week. We emailed Demand Progress members to alert them to the senator’s offer, and the idea took off. And it was heartening to see some of the more established progressive online activist groups like MoveOn—which we’d been leaning on for months—use this as their first foray into the SOPA/PIPA battle.

For better or worse, the bill died before Wyden had a chance to make good on his promise to read those names. I’d always envisioned him using the list to scold pro-PIPA senators by reading off the names of their states’ residents: Katherine of Essex Junction, Jimmy of Brattleboro, Arthur of Provo, Melanie of Park City—an hour of floor time and he could’ve read the names of two-thirds of Patrick Leahy and Orrin Hatch’s constituents. But I doubt that would’ve happened: For all of the talk of a Washington that’s embittered to unprecedented extremes, the Senate is so faux-collegial that watching C-SPAN 2 gives me toothaches.

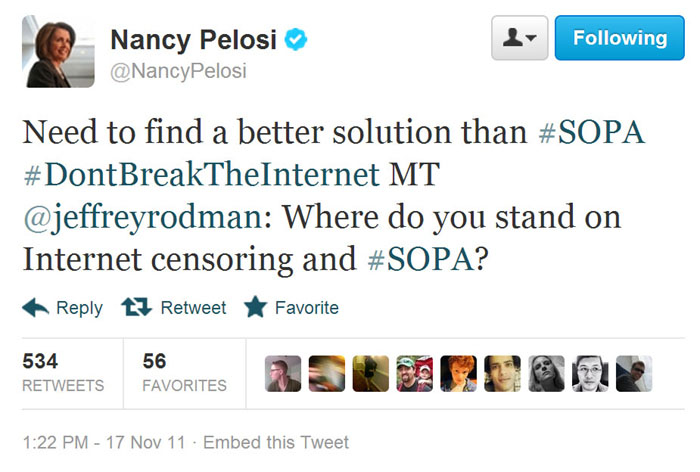

So there were cracks in the armor now: Nancy Pelosi, the leader of the House Democrats, had made her opposition to the bill known on American Censorship Day—via Twitter, no less. We’d collectively steered in a few million more emails to Congress. There was increased resonance among the public.

Well before the January 18, 2012 website blackouts, U.S. House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi was already opposed to SOPA. Above you can see Pelosi’s response to a constituent about SOPA.

But Lamar Smith was still pressing forward, insisting that he would mark up the bill before New Year’s and get it voted out of the Judiciary Committee, which he chairs.

PATRICK RUFFINI

Throughout the summer, the bill’s drafters on the House Judiciary Committee made public statements indicating they had heard the tech community’s concerns, and that the House bill would work to resolve many of them. In the second half of October, it was clear that nothing of the sort had occurred. Rumors began to emerge that SOPA would be worse than anything we’d seen to date, with Demand Progress, Don’t Censor the Net, the EFF and Public Knowledge sounding early alarms. PIPA’s changes from COICA had been a mixed bag—it removed a dreadful “blacklist” provision to encourage domain registrars and Internet service providers to block an informally cobbled-together list of “rogue” sites, while adding in the right-to-sue and search engine liability. The authors of SOPA not only refused to walk back any of PIPA’s most egregious provisions, but doubled down with new provisions bludgeoning the Digital Millennium Copyright Act’s safe harbors for third parties like Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook.

The DMCA required any website, including social networks and search engines (termed “intermediaries” as they routed most of the link-clicks on the Internet), to take down specific links to offending content at the rights-holder’s request. SOPA would go much further: takedowns of entire domains if owners were aware that their sites were being used to upload pirated content (alongside legitimate content), and continued to provide an avenue for that activity. This would create massive legal uncertainty for social platforms large and small, as it was a virtual certainty that any social or mobile startup would have users who would post pirated content at some point in time.

Looking back, while numerous players agreed that the December markup hearing in the House Judiciary Committee was the moment the legislative push effectively died, its introduction on October 26, 2011 definitively set in motion the chain of events that led to the Internet rising en masse in opposition.

Pre-SOPA, there was a sense that PIPA, though highly problematic, was not enough of a threat to Silicon Valley as a whole to inspire the companies to move their users to action. A top House aide interviewed for this book noted the widespread belief held by Hill staff that PIPA was simply not in the same league as SOPA; though distasteful, the Senate bill was a bitter pill that many tech companies could swallow with the right amendments. At the time, the best-case scenario was an amended PIPA that might placate the content industry for a few years.

Underlining this sense of inevitability, PIPA sailed through committee with minimal comment earlier in the year. The only company truly singled out by the Senate bill was Google, which would be held liable for pirate links in search

results. Yet as the process moved on, it seemed as though the content industry had ratcheted up the pressure on Congress to deal with other avenues of content discovery, like social media. Thus, SOPA could be read to cover social sites like Twitter and Facebook, demanding they actively take steps to prevent pirated content before it was posted. Not only were newer, venture-funded social and mobile startups the darlings of the Internet economy; they were exactly the tools one would use to defeat government censorship, whether earlier in 2011 in Egypt or, now, in the United States.

It was this dynamic, triggered by SOPA but not by PIPA, which caused the Internet—led by smaller players like Tumblr and reddit, more than by established players like Google—to go on nuclear alert. The added legal burden on Internet companies would fall less on large companies—Google could afford to spend tens of millions of dollars annually on a “content ID” platform for YouTube—than it would on venture-backed startups who wouldn’t get funded in the first place because of the legal risks associated with user-generated content. It was this point that was driven home by Brad Burnham of Union Square Ventures: many venture firms, including his, would not invest in music or video startups because of the likelihood they would be eventually be sued into oblivion. SOPA would take the same chilling effect, and apply it to the rest of the venture-backed technology ecosystem.

For entrepreneurs, engineers, VCs, and technology enthusiasts, the introduction of SOPA became a gut-punch moment that clarified the stakes for millions who identified with and made a living on the Internet. That’s when this became more than an issue, but a cause

“We were very disheartened once the bill got introduced,” explained one source involved in the fight. “It took a lot of the wind out of our sails. We thought we had made a lot of progress. We thought we had convinced them policy-wise there was a better way to do this.”

From there on out, there would be no talk of a deal and no compromise. Even the Capitol Hill veterans on the anti-SOPA/PIPA team understood that this was now guerrilla warfare. And Shore and Jochum’s team understood if there was an enemy common to all legislative proposals, it was time. Hundreds (if not thousands) of bills are introduced every year to great fanfare and little opposition, yet only a handful see the President’s desk. In the vast majority of cases, bills don’t die because they are voted down; they’re simply not gotten to and fade away. Getting to a floor vote on SOPA or PIPA would have been deadly, as floor outcomes are pre-ordained. From a legislator’s point of view, SOPA had to be seen as too controversial to risk even voting on.

“If you’re the proponent, if you’re pushing legislation, your job is to get it introduced and get off the floor as quickly as possible,” said Shore, describing a death-by-a-thousand-cuts victory strategy where the delay itself could be used to sow doubts about SOPA’s viability. “What I wanted to do was create a dead elephant carcass rotting in the sun with vultures and flies—and the longer that dead elephant carcass just sat in the sun, the more I knew we could kick the can and win.”

Meanwhile, as November rolled around, it would be clear that SOPA would be no PIPA in terms of near-unanimous assent from both sides of the aisle.

On October 1st, the Tea Party Patriots had made good on a long-standing commitment to speak out on our side of the issue. Numerous reporters had been calling me, looking for something to write about the populist, Tea Party opposition angle, and overnight, this development gave us exactly the boost we needed.

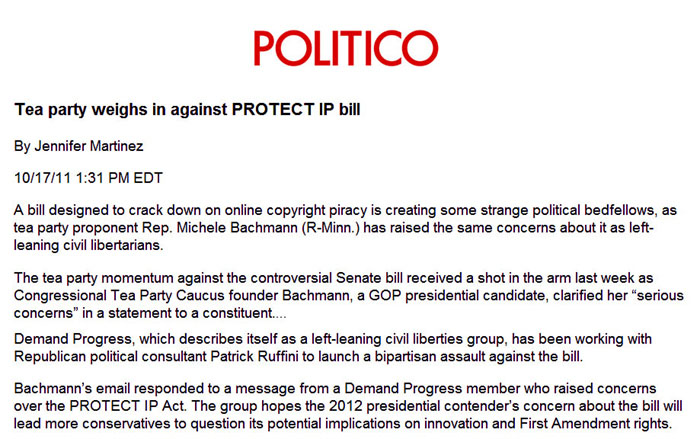

Two weeks later, seemingly out of nowhere, Tea Partier (and presidential candidate) Michele Bachmann added fuel to the fire with a constituent letter opposing the Senate bill. “I have serious concerns about government getting involved in regulation of the Internet,” wrote Bachmann. “And about ambiguities in this legislation which could lead to an explosion of destructive, innovation-stalling lawsuits.”

An anonymous constituent of Rep. Michele Bachmann contacted Demand Progress through Facebook and provided a response he/she had received to an anti-PIPA email they sent using Demand Progress’ website. We quickly alerted the media about the development, and at this fairly early point in the battle, it was seen as evidence that the Tea Party was on our side. The news article above noted the strange bedfellows alliance between the

Hacking Politics

editors

.

Following the bill’s introduction, Smith had scheduled a quick hearing on the bill for November 16th, and it was clear it would be a show trial. Of the six witnesses invited, only one would come from a group not supportive of the bill, Google’s copyright counsel Katherine Oyama. By deliberately ignoring Internet engineers, public interest groups, and the startup community, and singling out the biggest commercial player, Smith hoped to portray the opposition as one driven entirely by Google. Numerous others who volunteered to testify were shut out.

This moment was recalled by politicos and technologists alike as a turning point. Congressional hearings were supposed to be dispassionate fact-finding missions, but a bill with drastic effects on the architecture of the Internet featured not one engineer. “It was like an inquisition court for the MPAA,” recalled a senior House staffer, who was appalled at the damage this could do the public’s perception of the institution. The notion that Congress wouldn’t even listen to technical concerns probably radicalized Silicon Valley to the point where something big, like a blackout, was seen as the only way to get a point across.

Ahead of the hearing, ten House members—among them Ron Paul, Jared Polis, Issa, and Lofgren—sent a letter to Smith and ranking Democrat John Conyers warning that SOPA would target domestic websites and urging them to go slow. While Silicon Valley was heavily represented on the letter, the signatures also began to tell the story of the coalition’s broadening reach, with representatives from tech corridors in Austin, Boulder, and Pittsburgh signing on. The letter also meant that there would be a divided house on SOPA right off the blocks—the opposition numbered a dozen members, to the twenty-four who had signed on as SOPA co-sponsors as of November 15th. While not numerically even, it was better than the 40-to-1 split that persisted in the Senate. And it would mean that there would be substantial opposition in both parties, raising the specter of chaos on the House floor.

It was in late October, once the opposition had something concrete to rally against, that the lobbying effort kicked into high gear. And “high gear” for

technology companies still meant they were vastly outnumbered on Capitol Hill by their counterparts from the entertainment industry.

One lobbyist involved in the anti-SOPA effort described the scene early one morning in the cafeteria at the Rayburn House Office Building at the height of the debate. Their team would convene at around 7:30 a.m. for member and staff meetings, and had so much ground to cover with that no more than one person was ever in meeting with a member or staffer at once; usually, in-house lobbyists and consultants teamed up. They also noticed the entertainment lobby was out in full force, with around fifty lobbyists convened at eight or nine tables pushed together. The anti-SOPA lobbyists set forth for their first wave of meetings, and reconvened at 9 a.m.

When they returned, they noticed something odd: few, if any, of the pro-SOPA lobbyists appeared to have moved from their seats in an hour and a half. After their next round of meetings, they returned to compare notes and found the scene almost unchanged, with dozens of the same lobbyists still milling about in the cafeteria. The organizations that supported SOPA had spent $94 million on lobbying activity up to that point in 2011 (and $185.5 million the year before)—compared to $15.1 million across the entire technology industry. By all accounts, the proponents were running a professional, by-the-book lobbying operation, and doing so at massive scale. Yet, the lobbying colossus we all feared was starting to look like a sleeping giant.