Gulag (53 page)

In fact, the anecdotal evidence of suicide is great, and many memoirists remember them. One describes the suicide of a boy whose sexual favors were “won” by a criminal prisoner in a card game.

19

Another tells of a suicide of a Soviet citizen of German origins, who left a note for Stalin: “My death is a conscious act of protest against the violence and lawlessness directed against us, Soviet Germans, by the organs of the NKVD.”

20

One Kolyma survivor has written that in the 1930s, it became relatively common for prisoners to walk, quickly and purposefully, toward the “death zone,” the no-man’s-land beside the camp fence, and then to stand there, waiting to be shot.

21

Evgeniya Ginzburg herself cut the rope from which her friend Polina Melnikova hung, and wrote admiringly of her: “She had asserted her rights to be a person by acting as she had, and she had made an efficient job of it.”

22

Todorov again also writes that many survivors of both the Gulag and of the Nazi camps saw suicide as an opportunity to exercise free will: “By committing suicide, one alters the course of events—if only for the last time in one’s life—instead of simply reacting to them. Suicides of this kind are acts of defiance, not desperation.”

23

To the camp administration, it was all the same how prisoners died. What mattered to most was keeping the death rates secret, or at least semi-secret:

Lagpunkt

commanders whose death rates were found to be “too high” risked punishment. Although the rules were irregularly enforced, and although some did advocate the view that more prisoners ought to die, commanders of some particularly lethal camps did occasionally lose their jobs.

24

This was why, as some ex-prisoners have described, doctors were known to physically conceal corpses from camp inspectors, and why in some camps it was common practice to release dying prisoners early. That way, they did not appear in the camp’s mortality statistics.

25

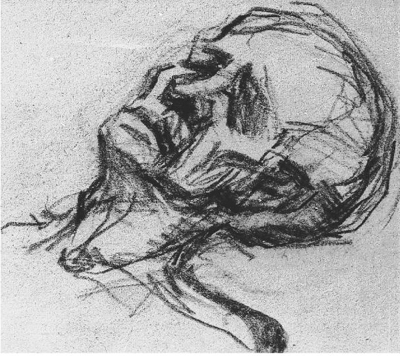

A Dying

Zek: a portrait by Sergei Reikhenberg, Magadan, date unknown

Even when deaths were recorded, the records were not always honest. One way or another, camp commanders made sure that doctors writing out prisoner death certificates did not write “starvation” as the primary cause of death. The surgeon Isaac Vogelfanger was, for example, explicitly ordered to write “failure of the heart muscle” no matter what the real cause of a prisoner’s death.

26

This could backfire: in one camp, the doctors listed so many cases of “heart attack” that the inspectorate became suspicious. The prosecutors forced the doctors to dig up the corpses, establishing that they had, in fact, died of pellagra.

27

Not all such chaos was deliberate: in another camp, the records were in such disarray that an inspector complained that “the dead are counted as living prisoners, escapees as imprisoned and vice versa.”

28

Prisoners were often kept deliberately ignorant of the facts of death as well. Although death could not be hidden altogether—one prisoner spoke of corpses lying “in a pile by the fence until the thaw”

29

—it could be shrouded in other ways. In many camps, corpses were removed at night, and taken to secret locations. It was only by accident that Edward Buca, forced to stay working late to meet his norm, saw what happened to corpses at Vorkuta:

After they had been stacked like timber in an open-sided shed until enough had accumulated for a mass burial in the camp cemetery, they were loaded, naked, on to sledges, heads on the outside, feet inside. Each body bore a wooden tag, a

birka

, tied to the big toe of the right foot, bearing its name and number. Before each sledge left the camp gate, the

nadziratel

, an NKVD officer, took a pickaxe and smashed in each head. This was to ensure that no one got out alive. Once outside the camp, the bodies were dumped into a

transeya

, one of several broad ditches dug during summer for this purpose. But as the number of dead mounted, the procedure for making certain they were really dead changed. Instead of smashing heads with a pickaxe, the guards used a

szompol

, a thick wire with a sharpened point, which they stuck into each body. Apparently this was easier than swinging the pick.

30

Mass burials may have also been kept secret because they too were technically forbidden—which is not to say they were uncommon. Former camp sites all over Russia contain evidence of what were clearly mass graves, and from time to time, the graves even re-emerge: the far northern permafrost not only preserves bodies, sometimes in eerily pristine condition, but it also shifts and moves with the annual freezes and thaws, as Varlam Shalamov writes: “The north resisted with all its strength this work of man, not accepting the corpses into its bowels . . . the earth opened, bearing its subterranean storerooms, for they contained not only gold and lead, tungsten and uranium, but also undecaying human bodies.”

31

Nevertheless, they were not supposed to be there and in 1946, the Gulag administration sent out an order to all camp commanders, instructing them to bury corpses separately, in funeral linen, and in graves which were no less than 1.5 meters deep. The location of the bodies was also meant to be marked not with a name, but with a number. Only the camp’s record-keepers were supposed to know who was buried where.

32

All of which sounds very civilized—except that another order gave camps permission to remove the dead prisoners’ gold teeth. These removals were meant to take place under the aegis of a commission, containing representatives of the camp medical services, the camp administration, and the camp financial department. The gold was then supposed to be taken to the nearest state bank. It is hard to imagine, however, that such commissions met very frequently. The more straightforward theft of gold teeth was simply too easy to carry out, too easy to hide, in a world where there were too many corpses.

33

For there

were

too many corpses—and this, finally, was the terrifying thing about a prison death, as Herling wrote:

Death in the camp possessed another terror: its anonymity. We had no idea where the dead were buried, or whether, after a prisoner’s death, any kind of death certificate was ever written . . . The certainty that no one would ever learn of their death, that no one would ever know where they had been buried, was one of the prisoners’ greatest psychological torments . . .

The barrack walls were covered with names of prisoners scratched in the plaster, and friends were asked to complete the data after their death by adding a cross and a date; every prisoner wrote to his family at strictly regular intervals, so that a sudden break in the correspondence would give them the approximate date of his death.

34

Despite prisoners’ efforts, many, many deaths went unmarked, unremembered, and unrecorded. Forms were not filled out; relatives were not notified; wooden markers disintegrated. Walking around old camp sites in the far north, one sees the evidence of mass graves: the uneven, mottled ground, the young pine trees, the long grass covering burial pits half a century old. Sometimes, a local group has put up a monument. More often, there is no marking at all. The names, the lives, the individual stories, the family connections, the history—all were lost.

Chapter 17

STRATEGIES OF SURVIVAL

I am poor, alone and naked,

I’ve no fire.

The lilac polar gloom

Is all around me . . .

I recite my poems

I shout them

The trees, bare and deaf,

Are frightened.

Only the echo from the distant mountains

Rings in the ears.

And with a deep sigh

I breathe easily again.

—Varlam Shalamov Neskolko moikh zhiznei

1

IN THE END, prisoners survived. They survived even the worst camps, even the toughest conditions, even the war years, the famine years, the years of mass execution. Not only that, some survived psychologically intact enough to return home, to recover, and to live relatively normal lives. Janusz Bardach became a plastic surgeon in Iowa City. Isaak Filshtinsky went back to teaching Arabic literature. Lev Razgon went back to writing children’s fiction. Anatoly Zhigulin went back to writing poetry. Evgeniya Ginzburg moved to Moscow, and for years was the heart and soul of a circle of survivors, who met regularly to eat, drink, and argue around her kitchen table.

Ada Purizhinskaya, imprisoned as a teenager, went on to marry and produce four children, some of whom became accomplished musicians. I met two of them over a generous, good-humored family dinner, during which Purizhinskaya served dish after dish of delicious cold food, and seemed disappointed when I could not eat more. Irena Arginskaya’s home is also full of laughter, much of it coming from Irena herself. Forty years later, she was able to make fun of the clothes she had worn as a prisoner: “I suppose you

could

call it a sort of

jacket

,” she said, trying to describe her shapeless camp overcoat. Her well-spoken, grown-up daughter laughed along with her.

Some even went on to lead extraordinary lives. Alexander Solzhenitsyn became one of the best-known, and best-selling, Russian writers in the world. General Gorbatov helped lead the Soviet assault on Berlin. After his terms in Kolyma and a wartime

sharashka

, Sergei Korolev went on to become the father of the Soviet Union’s space program. Gustav Herling left the camps, fought with the Polish army, and, although writing in Neapolitan exile, became one of the most revered men of letters in post-communist Poland. News of his death in July 2000 made the front pages of the Warsaw newspapers and an entire generation of Polish intellectuals paid tribute to his work—especially

A World Apart

, his Gulag memoir. In their ability to recover, these men and women were not alone. Isaac Vogelfanger, who himself became a professor of surgery at the University of Ottawa, wrote that “wounds heal, and you can become whole again, a little stronger and more human than before . . .”

2

Not all Gulag survivors’ stories ended so well, of course, which one would not necessarily be able to tell from reading memoirs. Obviously, people who did not survive did not write. Those who were mentally or physically damaged by their camp experiences did not write either. Nor did those who had survived by doing things of which they were later ashamed write very often either—or, if they did, they did not necessarily tell the whole story. There are very, very few memoirs of informers—or of people who will confess to having been informers—and very few survivors who will admit to harming or killing fellow prisoners in order to stay alive.

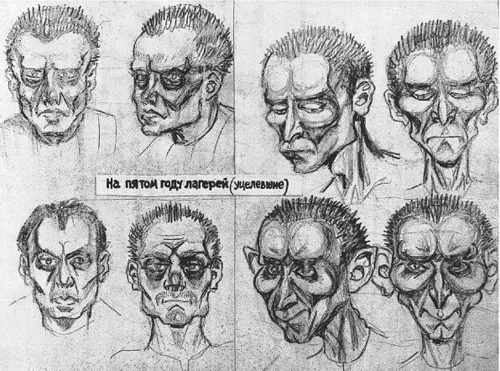

In the Fifth Year of the Camp (Survivors)

: prisoners’ faces, transformed over time— a drawing by Aleksei Merekov, a prisoner, place and date unknown

For these reasons, some survivors question whether written memoirs have any validity at all. Yuri Zorin, an elderly and not very forthcoming survivor whom I interviewed in his home city, Arkhangelsk, waved away a question I asked him about philosophies of survival. There weren’t any, he said. Although it might seem, from their memoirs, as if prisoners “discussed everything, thought about everything,” it was not like that, he told me: “The whole task was to live through the next day, to stay alive, not to get sick, to work less, to eat more. And that was why philosophical discussions, as a rule, were not held . . . We were saved by youth, health, physical strength, because there we lived by Darwin’s laws, the survival of the fittest.”

3

The whole subject of who survived—and why they survived—must therefore be approached very carefully. In this matter, there are no archival documents to rely upon, and there is no real “evidence.” We have to take the word of those who were willing to describe their experiences, either on paper or for an interviewer. Any one of them might have had reason to conceal aspects of their biographies from their readers.

With that caveat, it is still possible to identify patterns within the several hundred memoirs which have been published or placed in archives. For there were strategies for survival, and they were well-known at the time, although they varied a great deal, depending on a prisoner’s particular circumstances. Surviving a labor colony in western Russia in the mid-1930s or even late 1940s, when most of the work was factory work and the food was regular if not plentiful, probably did not require any special mental adjustments. Surviving one of the far northern camps—Kolyma, Vorkuta, Norilsk—during the hungry war years, on the other hand, often required huge reserves of talent and willpower, or else an enormous capacity for evil, qualities that the prisoners, had they remained in freedom, might never have discovered within themselves.

Without a doubt, many such prisoners survived because they found ways to raise themselves above the other prisoners, to distinguish themselves from the swarming mass of starving

zeks.

Dozens of camp sayings and proverbs reflect the debilitating moral effects of this desperate competition. “You can die today—I’ll die tomorrow,” was one of them. “Man is wolf to man”—the phrase Janusz Bardach used as the title of his memoir—was another.

Many ex

-zeks

speak of the struggle for survival as cruel, and many, like Zorin, speak of it as Darwinian. “The camp was a great test of our moral strength, of our everyday morality, and 99 percent of us failed it,” wrote Shalamov.

4

“After only three weeks most of the prisoners were broken men, interested in nothing but eating. They behaved like animals, disliked and suspected everyone else, seeing in yesterday’s friend a competitor in the struggle for survival,” wrote Edward Buca.

5

Elinor Olitskaya, with her background in the pre-revolutionary social democratic movement, was particularly horrified by what she perceived as the amorality of the camps: while inmates in prisons had often cooperated, the strong helping the weak, in the Soviet camps every prisoner “lived for herself,” doing down the others in order to attain a slightly higher status on the camp hierarchy.

6

Galina Usakova described how she felt her personality had changed in the camps: “I was a well-behaved girl, well brought up, from a family of intelligentsia. But with these characteristics you won’t survive, you have to harden yourself, you learn to lie, to be hypocritical in various ways.”

7

Gustav Herling elaborated further, describing how it is that the new prisoner slowly learns to live “without pity”:

At first he shares his bread with hunger-demented prisoners, leads the night-blind on the way home from work, shouts for help when his neighbor in the forest has chopped off two fingers, and surreptitiously carries cans of soup and herring-heads to the mortuary. After several weeks he realizes that his motives in all this are neither pure nor really disinterested, that he is following the egotistic injunctions of his brain and saving first of all himself. The camp, where prisoners live at the lowest level of humanity and follow their own brutal code of behavior toward others, helps him to reach this conclusion. How could he have supposed, back in prison, that a man can be so degraded as to arouse not compassion but only loathing and repugnance in his fellow prisoners? How can he help the night-blind, when every day he sees them being jolted with rifle-butts because they are delaying the brigade’s return to work, and then impatiently pushed off the paths by prisoners hurrying to the kitchen for their soup; how visit the mortuary and brave the constant darkness and stench of excrement; how share his bread with a hungry madman who on the very next day will greet him in the barrack with a demanding, persistent stare . . . He remembers and believes the words of his examining judge, who told him that the iron broom of Soviet justice sweeps only rubbish into its camps . . .

8

Such sentiments are not unique to the survivors of Soviet camps. “If one offers a position of privilege to a few individuals in a state of slavery,” wrote Primo Levi, an Auschwitz survivor, “exacting in exchange the betrayal of a natural solidarity with their comrades, there will certainly be someone who will accept.”

9

Also writing of German camps, Bruno Bettelheim observed that older prisoners often came to “accept SS values and behavior as their own,” in particular adopting their hatred of the weaker and lower-ranking inhabitants of the camps, especially the Jews.

10

In the Soviet camps, as in the Nazi camps, the criminal prisoners also readily adopted the dehumanizing rhetoric of the NKVD, insulting political prisoners and “enemies,” and expressing disgust for the

dokhodyagi

among them. From his unusual position as the only political prisoner in a mostly criminal

lagpunkt

, Karol Colonna-Czosnowski was able to hear the criminal world’s view of the politicals: “The trouble is that there are just too many of them. They are weak, they are dirty, and they only want to eat. They produce nothing. Why the authorities bother, God only knows . . .” One criminal, Colonna-Czosnowski writes, said he had met a Westerner in a transit camp, a scientist and university professor. “I caught him eating, yes, actually eating, the half-rotten tail fin of a Treska fish. I gave him hell, you can imagine. I asked him if he knew what he was doing. He just said he was hungry . . . So I gave him such a wallop in the neck that he started vomiting there and then. Makes me sick to think about it. I even reported him to the guards, but the filthy old man was dead the following morning. Serves him right!”

11

Other prisoners watched, learned and imitated, as Varlam Shalamov wrote:

The young peasant who has become a prisoner sees that in this hell only the criminals live comparatively well, that they are important, that the all-powerful camp administration fear them. The criminals always have clothes and food, and they support each other . . . it begins to seem to him that the criminals possess the truth of camp life, that only by imitating them will he tread the path that will save his life . . . . the intellectual convict is crushed by the camp. Everything he valued is ground into the dust while civilization and culture drop from him within weeks. The method of persuasion is the fist or the stick. The way to induce someone to do something is by means of a rifle butt, a punch in the teeth . . .

12

And yet—it would be incorrect to say there was no morality in the camps at all, that no kindness or generosity was possible. Curiously, even the most pessimistic of memoirists often contradict themselves on this point. Shalamov himself, whose depiction of the barbarity of camp life surpasses all others, at one point wrote that “I refused to seek the job of foreman, which provided a chance to remain alive, for the worst thing in a camp was the forcing of one’s own or anyone else’s will on another person who was a convict just like oneself.” In other words, Shalamov was an exception to his own rule.

13

Most memoirs also make clear that the Gulag was not a black-and-white world, where the line between masters and slaves was clearly delineated, and the only way to survive was through cruelty. Not only did inmates, free workers, and guards belong to a complex social network, but that network was also constantly in flux, as we have seen. Prisoners could move up and down the hierarchy, and many did. They could alter their fate not only through collaboration or defiance of the authorities but also through clever wheeling and dealing, through contacts and relationships. Simple good luck and bad luck also determined the course of a typical camp career, which, if it was a long one, might well have “happy” periods, when the prisoner was established in a good job, ate well, and worked little, as well as periods when the same prisoner dropped into the netherworld of the hospital, the mortuary, and the society of the

dokhodyagi

who crowded around the garbage heap, looking for scraps of food.