Grumbles from the Grave (25 page)

Read Grumbles from the Grave Online

Authors: Robert A. Heinlein,Virginia Heinlein

Tags: #Authors; American - 20th century - Correspondence, #Correspondence, #Literary Collections, #Letters, #Heinlein; Robert A - Correspondence, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #20th century, #Authors; American, #General, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Science Fiction, #American, #Literary Criticism, #Science fiction - Authorship, #Biography & Autobiography, #Authorship

No more acknowledgments of fan magazines sent to me—it simply results in more of them and requests for free copy.

In short, no more of

anything

unless it durn well suits me and adds to my own pleasure in life. More and more, over the years, strangers have been nibbling away at my time. It has reached the point where, if I would let them,

all

of my working time would be wasted on the demands of strangers. So I am lowering the boom on all of it—and if this makes me a rude son of a bitch, so be it. My present life expectancy is seventeen years; I'm damned if I will spend it answering silly questions about "Where do you get your ideas?" and "Why did you take up the writing of science fiction?" several thousand or more times. I hereby declare that an author has

no

responsibility of any sort to the public . . . other than the responsibility to write stories as well as he knows how.

If I can stick to this, I should get in quite a lot more writing, and quite a lot more healthy work with pick and shovel and trowel—and a judicious mixture of these two may enable me to stretch that life expectancy quite a bit. But I'm not going to let those remaining years be nibbled away and wasted by the trivia that some thousands of faceless strangers seem to feel is their right to demand from anyone in a semi-public occupation.

July 10, 1967: Robert A. Heinlein to Lurton Blassingame

Herewith is a curious letter from an instructor, ----, at the U. of Oregon. I was about to tell him that I could not stop him, but not to let me see the result—but I decided that I had better let you see this and get your advice and/or veto. If Mr. ---- does this adaptation "just for fun," as he proposes, I suspect that he will then fall in love with his own efforts and get very itchy to produce it. Which could be embarrassing. Lurton, even though "Green Hills" is a short, I think it has possibilities—someday—as a musical motion picture. So I am hesitant to authorize anything which might cloud the MP or stage rights. What shall I tell him? Or do you prefer to write to him? (I'm not urging you to—not trying to shove it on you. But I do want your advice.)

October 12, 1967: Margo Fischer [secretary to] Lurton Blassingame to Robert A. Heinlein

A drunk began calling at 3:15 insisting on Heinlein's phone number . . . After telling him at least seven times that he would have to write a letter which would be forwarded airmail, he became sarcastic and went on and on. After 15 minutes I told him I was hanging up, and I did. He was incoherent and it was impossible to tell him he had to write a letter. He said he would wire. He wanted to know about "—We Also Walk Dogs." I told him it was in an anthology published by World. He'll probably call you and be abusive about me. Over and over he kept saying, "Mam, Mam"—long silence, then he'd say, "It's a hard world." Silence. Then, "We should all be courteous to one another." Etc.

February 28, 1968: Margo Fischer to Robert A. Heinlein

Here's a little ego boo for you.

The telephone just rang. A voice said, "I was told I could get some information from you. About one of your clients. About Robert Heinlein." Cagey Margo. "Who is this?" "I'm nobody—that is, nobody in the business," he said. "Just a Heinlein fan." Me again—"Well, what did you want to know?"

He wanted to know when Heinlein was going to have another book. "He hasn't written anything for some time," was the complaint. "I have two favorite authors. Michener and Heinlein. Michener just came out with one and I was hoping I could make it a double red-letter day."

Then he added, "Heinlein is the one bright spot in this whole fantasy-science-fiction world." A pause. "

Moon

is the last one he's written, right?" Then I said, "Have you read

Stranger

?" Answer: "Four times." Finally, "Just one more thing—how long does it usually take him to write a book?"

HOW CAN YOU DEPRIVE YOUR FANS A MINUTE LONGER, BOB?

CHAPTER IX

MISCELLANY

STUDY

April 10, 1961: Robert A. Heinlein to Lurton Blassingame

No, we are not contemplating any immediate ventures into Arabic-speaking lands; all of Africa and the Middle East are too unstable at the present time to be attractive—besides, we've been there a couple of times. Tackling Arabic is simply to keep my mind loosened up with something new. It could have been any language I don't know, but I picked it because it is one of the five "critical" languages as listed by the State Department—i.e., an important language which is known by too few Americans; they have plenty of people who know French, German, Spanish, and such. One of the five is Russian and I didn't want to duplicate what Ginny has already done (besides, Russian is

very

hard; Arabic is relatively simple, save for the odd alphabet) and two of the critical languages are tonal languages, and my ear for tones is not very good; I don't think I could learn them as an adult. But I must admit that I have made no real progress as yet; I've nothing to force me to a schedule and there are too many other things that demand attention.

But I would like to, in time, be able to be of some use to the country by knowing a language which is needed. But if it is never of any use that way, I find the study of strange languages rewarding per se; I always learn a lot about the people and the culture when I tackle one.

But I have a dozen subjects that I want to study. I would like to go back to school and take a formal course in electronics; it has changed so much since I studied it more than thirty years ago—and I may, some day soon. About twenty years ago I dropped out of a figure-drawing class because I needed to buckle down and pay off a mortgage—and that turned me into a writer and I haven't been back. But I want to go back, it is something I love doing—and I would like to add a wing to this house and get into sculpture again, too, but simply signing up for a figure sketching class is more likely. I am not a still-life artist. There are only five things really worth drawing; four of them are pretty girls and the fifth is cats.

PREDICTIONS

(147)

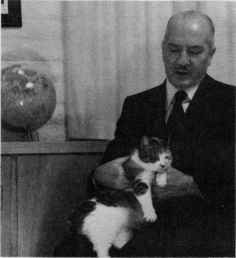

Robert Heinlein with Teense in the dining room at Bonny Boon.

March 13, 1947: Robert A. Heinlein to

Saturday Evening Post

. . . I could list many more variables—never mind. Swami Heinlein will now gaze into the crystal ball. First unmanned rocket to the Moon in five years. First manned rocket in ten years. Permanent base there in fifteen years. After that, anything! Several decades of exploring the solar system with everyone falling all over each other to do it first and stake out claims.

However, we may wake up some morning and find that the Russians have quietly beaten us to it, and that the Lunar S.S.R.—eight scientists and technicians, six men, two women—has petitioned the Kremlin for admission of the Moon to the USSR. That's another unknown variable.

And keep your eyes on the British—the British Interplanetary Society is determined to get there first.

The worst thing about this business of predicting technical advance is that there is an almost insuperable tendency to be too conservative. In almost every case, correct prophecy of the Jules Verne type has failed in the one respect of putting the predicted advance too far in the future. Based on past record, if the figures I gave above are wrong, they are almost certainly wrong in being too timid. Space flight may come even sooner. I

know

that, yet I have trouble believing it.

November 7, 1949: Robert A. Heinlein to Lurton Blassingame

. . . My real claim to being a student of the future, if I have a claim, lies in noting things going on now and then in examining speculatively what those trends could mean—particularly with respect to atomics, space travel, geriatrics, genetics, propaganda techniques, and food supply. To evaluate my success in such it would be necessary for a person to have some familiarity with my published writings. But I don't intend to dig through my writings and say, "Look, here in

Beyond This Horizon

I predicted the robot-secretary recording telephone and now it has been patented!" I

did

—and it

has

—but that doesn't mean anything. The short-term prediction of gimmicks isn't prophecy; it is merely a parlor trick.

PROPHECY

September 24, 1949: Robert A. Heinlein to Lurton Blassingame

Editor's Note: With the motion picture about to start shooting, and with Robert at work on the next juvenile for Scribner's, a request came in from

Cosmopolitan

for an article about prediction of what the U. S. would be like in the year 2000. In this letter Robert was asking for information about what sort of article the editors would like—he made some suggestions about it.

When the article was finished,

Cosmopolitan

turned it down. It sold to

Galaxy

and was published as "Pandora's Box." The article was periodically updated, and the most recent version can be found in

Expanded Universe

.

. . . Under "treatment" come a couple of other questions: This article is to be prophetic. Fine—that's my business; I make my living as a professional prophet of what science will bring to us. But such an article—nonfiction—must consider and to some extent report the

present

status in various fields before the author can go out into the wild blue yonder with predictions. Therefore, I inquire how much reporting do they [

Cosmopolitan

] want of the sort which one finds in

Scientific American

,

Science News Letter

,

Nature

, etc., and how much speculation or prediction do they want? The two things are closely related, but are not the same thing. Also, how far in the future shall I go? (For example, everybody knows that the cancer men, radiation men, and biochemists stand an excellent chance of perfecting selective radiation treatment of certain types of cancer in the very near future by finding ways to bond short half-life isotopes to some compound which a particular type of cancer will pick up selectively.)

Or should I go well into the future and consider the necessary statistical effect of food supply, geriatrics, life-span research, public health, etc., in forcing the development of a brand-new art, planetary engineering, as it affects the growth of colonies on the planet Mars?

* * *

The synthesizing prophet has another advantage over the specialist; he knows, from experience and by examining the efforts of other prophets

of his type

in the past that his "wildest" predictions are more likely to come true than the ones in which he lost his nerve and was cautious. This statement is hard to believe but can be checked by comparing past predictions with present facts. (Show me the man who honestly believed in the atom bomb twenty years ago—but H. G. Wells predicted it in 1911.) (The "wild fantasies" of Jules Verne turned out to be much too conservative.)

How can one spot a competent synthesizing prophet? Only by his batting average. If

Cosmopolitan

thinks my record of accomplished predictions is good enough to warrant it, then let's by all means go all out and I'll make some serious predictions that will make their hair stand on end. If they want to play safe, I'll do an Inquiring Reporter job and we'll limit it to what the specialists are willing to say. But I can tell them ahead of time that such an article will be more respectable today and quite unrespected ten years from now—for that is no way to whip up successful prophecy.

* * *

. . . I would proceed as follows:

First, I would cut down the field by limiting myself to (a) subjects in which the changes would matter to the readers personally and not too remotely. A new principle in electronics I would ignore unless I saw an important tie into the lives of ordinary people, (b) subjects which are dramatic and entertaining either in themselves or in their effects. Space travel is such a subject, both ways. So is life-span research. On the other hand, a cure for hoof-and-mouth disease, while urgently needed, is much harder to dramatize, (c) subjects which can be explained. The connection between parapsychology and nuclear engineering is dramatic potentially but impossible to explain convincingly.

* * *

Since the article is for popular consumption I would wish to hook it, if possible, with some startling piece of quoted dialog, use illustrative anecdote if possible, and end it with some dramatic prediction.

December 20, 1955: Robert A. Heinlein to Lurton Blassingame

Please tell Howard Browne [editor of

Amazing Stories

and

Fantastic

] that I accept his incredible offer and that ms. will arrive by 10 January—but that I expect a copy of that celebration issue, inscribed by him to me, or I shall go into the corner and stick pins in wax images.

I can't imagine what I could possibly say that would be worth $100 for two pages; that isn't even long enough for a horoscope. But if they want to throw away their money in my direction I will go along with the gag and do my damndest to entertain the cash customers. Fortunately, I shall be dead before my "prophecies" can be checked on.

January 5, 1956: Robert A. Heinlein to Lurton Blassingame

Here is the ms. for Howard Browne. I discovered that 500 words were too cramping for what I wanted to say, so I called him yesterday (I assumed that you were at Ilikite, it being Wednesday) and got his authorization to let it run to its present length. No increase in the fee, of course, as the added length was entirely for my convenience.