Grumbles from the Grave (21 page)

Read Grumbles from the Grave Online

Authors: Robert A. Heinlein,Virginia Heinlein

Tags: #Authors; American - 20th century - Correspondence, #Correspondence, #Literary Collections, #Letters, #Heinlein; Robert A - Correspondence, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #20th century, #Authors; American, #General, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Science Fiction, #American, #Literary Criticism, #Science fiction - Authorship, #Biography & Autobiography, #Authorship

We finally managed to get moved into our new house. It is far from finished; while the outer shell is closed in solid, the interior is a forest of studs and butcher paper temporary partitions. We do have plumbing and we do have kitchen fixtures and we do have heating; we'll make out.

I am still much badgered by bills, mechanics, unavoidable chores, and such, but I have a place to write and should now be able to continue at it fairly steadily.

February 11, 1951: Robert A. Heinlein to Lurton Blassingame

. . . We managed to spend $6,000 in six days—which turns out to be awfully hard work. I have been trying to buy and get onto the job every bit of metal, every last stick of wood, needed to complete this house.

Incidentally, it just nicely cleaned us out again. The laughable price freeze [because of the wartime economy] came much too late to do a man who is building any good. But, with the material on hand, I now know that I can and will finish.

May 13, 1951: Robert A. Heinlein to Lurton Blassingame

We put up the ceiling this past week; tomorrow we paint it and start putting up wall paneling. The house looks like an Okie camp. Sunday is the only day I can do paperwork as I have mechanics working both days and evenings. I put in about a fourteen-hour day each day and am gradually losing my bay window. Housebuilding is most impractical, but we are slowly getting results.

June 10, 1951: Robert A. Heinlein to Lurton Blassingame

It is ten-thirty and I must be up around six. Today being Sunday I worked all day alone on the house. It continues to be an unending headache, but we are beginning to see the end—about another month if we don't run into more trouble. The biggest headache, now that the bank account is refreshed, is finding and keeping mechanics. This town is in a war building boom and every mechanic has his pick of many jobs. I should have four or five working; I have two, plus myself. I work at any trade which is missing at the moment. Fortunately, I can do most of the building trades myself, after a fashion. I have a stone mason doing cabinet work, which will give you some idea of the difficulties of getting help. Often I think of your comment, more than a year ago, that you hoped I would not have trouble but never knew of a case of a person building his own home who did not have lots of trouble. Well, we surely have had it, but the end is in sight—if I don't go off my rocker first.

What am I saying? I

am

off my rocker!

(118)

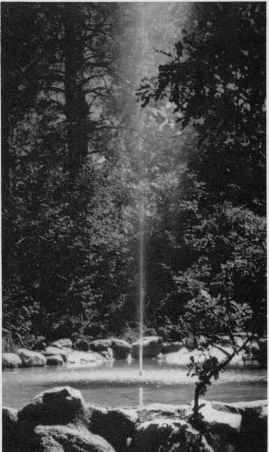

"Project Stonehenge." The creation of a decorative pool was undertaken by the Heinleins alone—and made them a two-wheelbarrow family.

April 17, 1961: Robert A. Heinlein to Lurton Blassingame

Actually, I am not studying Arabic very much nor am I writing; I am moving massive boulders with pick and shovel and crowbar and block and tackle, building an irrigation dam—a project slightly smaller than the Great Pyramid but equal to Stonehenge. I no longer have any fat on my tummy at all but have a fine new collection of aches, pains, bruises, and scratches.

May 15, 1961: Robert A. Heinlein to Lurton Blassingame

We are now a two-wheelbarrow family. That accounts for the delay.

Don't brush it off. Are

you

a two-wheelbarrow family? How many two-wheelbarrow families do you know? I mean to say: two-Cadillac families are common; there are at least twenty in our neighborhood, not counting Texans. But we are the only two-wheelbarrow family I know of.

It came about like this: I started building Ginny's irrigation dam. Simultaneously Ginny was spreading sheep manure, peat moss, gravel, etc., and it quickly appeared that every time she wanted the wheelbarrow I had it down in the arroyo—and vice versa. A crisis developed, which we resolved by going whole hog and phoning Sears for a second one. Now we are both happily round-shouldered all day long, each with his (her) own wheelbarrow.

(Live a little! Buy yourself a second one. You don't know what luxury is until you have a wheelbarrow all your own, not constantly being borrowed by your spouse.)

This dam thing (or damn' thing) I call (with justification)

Project Stonehenge;

it is the biggest civil engineering feat since the Great Pyramid. The basis of it is boulders, big ones, up to two or three tons each—and I move them into place with block and tackle, crowbar, pick and shovel, sweat, and clean Boy Scout living. Put a manila sling around a big baby, put one tackle to a tree, another to another tree, take up hard and tight with all my weight on each and lock them—then pry at the beast with a ninety-pound crowbar of the sort used to move freight cars by hand, gaining an inch at a time.

Then, when at last you have it tilted up, balanced, and ready to fall forward, the sling slips and it falls back where it was. This has been very good for my soul.

(And my waist line—I am carrying no fat at all and am hard all over. Well, moderately hard.)

Editor's Note: Robert enjoyed doing rock work, and the grounds were greatly improved by three decorative pools and revetments done with rocks.

SANTA CRUZ COUNTY

(122)

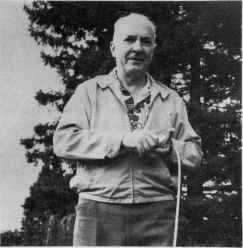

Heinlein surveying at Bonny Doon. The Heinleins moved to Santa Cruz in the mid-sixties.

Editor's Note: We loved our home in Colorado Springs—Robert had done so much in the way of rock work outside, and we had lavished our care on it for some years.

But there were two reasons why we had to leave. One was my health. For some years, it had become increasingly evident that I could not stand the altitude—I had "mountain sickness." The other reason was that the house was too small for our files of papers and books. We left Colorado on the seventeenth anniversary of our marriage, to look on the West Coast for land for building. Three months were spent on this quest before we bought the land in Santa Cruz.

We remained in that house until 1987, at which time we found that it was too far from medical services, which Robert needed quickly at times. So we looked in Carmel, and found a suitable house, although it had all the drawbacks of the ones we had decided against in Santa Cruz.

February 1, 1966: Robert A. Heinlein to Lurton Blassingame

We moved into this house because it is twenty miles closer to the land we finally bought than is the apartment in Watsonville and is the closest rental we could find to our new land—not very close at that: nine miles in a straight line, fourteen by road, twenty-six minutes by car. But the house, besides being nearer, is a vast improvement on the apartment. It is all on one floor, has three bedrooms (which gives me a separate room for my study), two full baths, a dishwasher, a garbage grinder, a double garage, and a gas furnace with forced air instead of electric strip heaters. It is an atrocity in other respects—such as a large view window which has an enchanting view solely of a blank wall ten feet away—but we will be comfortable in it and reasonably efficient until we get our new house built.

The dismal saga of how we almost-not-quite bought another parcel of land is too complex to tell in detail. Those forty-three acres of redwoods located spang on the San Andreas Fault—Ginny thought I had my heart set on them, I thought she had her heart set on them . . . and in fact both of us were much taken by them. It is an utterly grand piece of land—very mountainous, two rushing, gushing mountain streams with many waterfalls, thousands of redwoods up to two hundred feet tall. But in fact it was better suited to playing Götterdämmerung than it was to building a year-round home. Most of the acreage was so dense as to be of no possible use, and the forest was so dense that the one site for a house would receive sunlight perhaps three hours each day. Mail delivery would be a mile away . . .

* * *

I agreed but insisted that we shop first for houses . . . as designing and building a house would cost me, at a minimum, the time to write at least one book as a hidden expense. So we did—but it took me only a couple of days to admit that it was impossible to buy a house ready built which would suit me, much less Ginny. Firetraps built for flash, with other people's uncorrectable mistakes built into them! (Such as a lovely free-form swimming pool so located as to be overlooked by neighbors' windows! Such as Romex wiring, good for only five years, concealed in the wooden walls of a house . . . )

The new property has none of the hazards of the property we backed away from buying. It is on a well-paved county road and has 220-volt power and telephone right at the property line. It does not have gas (we expect to use butane for cooking, fuel oil for heating), does not have sewer, does not have municipal water. So we'll use a septic tank and a spread field. It has its own spring, which delivers a steady flow at present of 6,000 gallons per day. We had a very heavy rainstorm over this last weekend, so I went up and checked the flow again and was pleased to find that it had not increased at all—i.e., it apparently comes from deep enough that one storm does not affect it. I'll keep on checking it during the coming dry season but we were assured by a neighbor (not the owner) that the spring had not failed in the past seventy-five years. I plan to try to develop it still farther and plan to install not only a swimming pool but two or three ornamental pools and ponds of large capacity against the chance that we might run short of water in the dry season. But I'm not worried about it; it is redwood country and where there are redwoods there is water.

The land is a gentle, rolling slope, with the maximum pitch being around one in ten and the house site level and about forty feet higher than the road. The parcel is clear but it has on it some eight or nine clumps of redwoods, plus a few big, old live oaks which look like pygmies alongside the sequoias. These are sequoia sempervirens, the coastal redwood, and ours are second growth, about a hundred feet tall, up a yard thick, and around ninety years old. There are also a few other conifers, ponderosa, fir, cypress, etc., but they hardly show up among the redwoods. I have not yet conducted a tree census, but we seem to have something in excess of a hundred of the very big trees, plus younger ones of various sizes. Each redwood clump is associated with the cut stumps of the first growth, six or eight feet thick and eight or ten feet high. Since redwood does not decay, they are still there, great silvery free-form sculptures. Ginny is planning one garden designed around a group of them.

I am very busy designing the house. I am anxious to start building as soon as possible as I really can't expect to get any writing done, at least until this new house is designed and fully specified. Building becomes a compulsive fever with me; it drives everything else out of my mind.

April 6, 1966: Robert A. Heinlein to Lurton Blassingame

. . . I'm still bending over a hot drawing board—I'm very slow, for I am

not

an architect and have to look up almost every detail. But the end is in sight. As soon as I can get a water system hooked onto our spring and a driveway bulldozed, we will probably buy a thirdhand trailer and move onto the place during building—Ginny is now willing to do this in order to move our cat here. There has been a rabies scare in Colorado Springs; all animals are under a quarantine and we are having to keep him in a kennel with our vet.

June 22, 1966: Virginia Heinlein to Lurton Blassingame

[Robert] is still relaxing, since when he spends too much time out of bed, he tires very easily . . .

Every once in a while I hear some sounds which seem to indicate that our cat is trying to despoil a bird's nest nearby . . . He seems to like it here, hasn't started that hike back to Colorado which I predicted.

July 1, 1966: Robert A. Heinlein to Lurton Blassingame

I have received, but not yet read,

The Psychology of Sleep

—but will read it as soon as I can stay awake that long; I want to find out why I am so sleepy. I seem to be practically well now, save that I am sleepy all the time; I'm sleeping twelve and fourteen hours a day. I get up late, have breakfast, and can barely stay awake long enough to go back to bed—get up again, get a couple hours of paperwork done (with great effort), then take a nap. Resolve to get something done after dinner but find myself going to bed again. It is not unpleasant save that I am totally useless and the work piles up. The incision seems to have healed perfectly and my surgeon says that after the 15th of July I can do anything I wish—lift 200 lbs . . . which will be remarkable as I never could in the past. (Oh, off the floor, yes—but not a clean press up into the air.)