Grit (37 page)

Authors: Angela Duckworth

Pete’s idol, basketball coach John Wooden, was fond of saying, “Success is never final;

failure is never fatal. It’s courage that counts.” What I wanted to know is how a culture of grit continues not just in the afterglow of success, but in the aftermath of failure. What I wanted to know is how Pete and the Seahawks found the courage to continue.

As I look back on it now, my visit has an “in the moment” feel:

My appointment begins with a meeting in Pete’s office—yes, it’s the corner office, but no, it’s not huge or fancy, and the door is apparently

always

open, literally, allowing loud rock music to spill out into the hallway. “Angela,” Pete leans in to ask, “how can this day be helpful to you?”

I explain my motive. Today I’m an anthropologist, here to take notes on Seahawks culture. If I had a pith helmet, I’d be wearing it.

And that, of course, gets Pete all excited. He tells me that it’s not just one thing. It’s a million things. It’s a million details. It’s substance and it’s style.

After a day with the Seahawks, I have to agree. It’s countless small things, each doable—but each so easy to botch, forget, or ignore. And though the details are countless, there are some themes.

The most obvious is language. One of Pete’s coaches once said, “I speak fluent Carroll.” And to speak Carroll is to speak fluent Seahawk:

Always compete. You’re either competing or you’re not. Compete in everything you do. You’re a Seahawk 24-7. Finish strong. Positive self-talk. Team first.

During my day with the team, I can’t tell you how many times someone—a player, a coach, a scout—enthusiastically offers up one of these morsels, but I can tell you I don’t once hear variations. One of Pete’s favorite sayings is “No synonyms.” Why not? “If you want to communicate effectively, you need to be clear with the words you use.”

Everybody I meet peppers their sentences with these Carrollisms. And while nobody has quite the neutron-powered, teenage energy of the sixty-three-year-old head coach, the rest of the Seahawks family, as they like to call themselves, are just as earnest in helping me decode what these dictums actually mean.

“Compete,” I’m told, is not what I think it is. It’s not about triumphing over others, a notion I’ve always been uneasy about. Compete means excellence. “Compete comes from the Latin,” explains Mike Gervais, the competitive-surfer-turned-sports-psychologist who is one of Pete’s partners in culture building. “Quite literally, it means

strive together

. It doesn’t have anything in its origins about another person losing.”

Mike tells me that two key factors promote excellence in individuals

and in teams: “deep and rich support and relentless challenge to improve.” When he says that, a lightbulb goes on in my head. Supportive and demanding parenting is psychologically wise and encourages children to emulate their parents. It stands to reason that supportive and demanding leadership would do the same.

I begin to get it. For this professional football team, it’s not solely about defeating other teams, it’s about pushing beyond what you can do today so that tomorrow you’re just a little bit better. It’s about excellence. So, for the Seahawks,

Always compete

means

Be all you can be, whatever that is for you. Reach for your best.

After one of the meetings, an assistant coach catches up to me in the hallway and says, “I don’t know if anyone’s mentioned

finishing

to you.”

Finishing?

“One thing we really believe in here is the idea of finishing strong.” Then he gives me examples: Seahawks finish a game strong, playing their hearts out to the last second on the clock. Seahawks finish the season strong. Seahawks finish every drill strong. And I ask, “But why just finish strong? Doesn’t it make sense to start strong, too?”

“Yes,” the coach says, “but starting strong is easy. And for the Seahawks, ‘finishing’ doesn’t literally mean ‘finishing.’ ”

Of course not. Finishing strong means consistently focusing and doing your absolute best at every moment, from start to finish.

Soon enough, I realize it’s not only Pete doing the preaching. At one point, during a meeting attended by more than twenty assistant coaches, the entire room spontaneously breaks out into a chant, in perfect cadence:

No whining. No complaining. No excuses

. It’s like being in a choir of all baritones. Before this, they sang out:

Always protect the team

. Afterward:

Be early

.

Be early? I tell them that, after reading Pete’s book, I made “Be early” a resolution. So far, I had yet to be early for almost anything. This elicited some chuckles. Apparently, I’m not the only who struggles

with that one. But just as important, this confession gets one of the guys talking about why it’s important to be early: “It’s about respect. It’s about the details. It’s about excellence.” Okay, okay, I’m getting it.

Around midday, I give a lecture on grit to the team. This is after giving similar presentations to the coaches and the scouts, and before talking to the entire front-office staff.

After most of the team has moved on to lunch, one of the Seahawks asks me what he should do about his little brother. His brother’s very smart, he says, but at some point, his grades started slipping. As an incentive, he bought a brand-new Xbox video-game console and placed it, still in its packaging, in his brother’s bedroom. The deal was that, when the report card comes home with A’s, he gets to unwrap the game. At first, this scheme seemed to be working, but then his brother hit a slump. “Should I just give him the Xbox?” he asks me.

Before I can answer, another player says, “Well, man, maybe he’s just not

capable

of A’s.”

I shake my head. “From what I’ve been told, your brother is plenty smart enough to bring home A’s. He was doing it before.”

The player agrees. “He’s a smart kid. Trust me, he’s a smart kid.”

I’m still thinking when Pete jumps up and says, with genuine excitement: “First of all, there is absolutely no way you give that game to your brother. You got him motivated. Okay, that’s a start. That’s a beginning. Now what? He needs some

coaching

! He needs someone to explain what he needs to do, specifically, to get back to good grades! He needs a plan! He needs your help in figuring out those next steps.”

This reminds me of something Pete said at the start of my visit: “Every time I make a decision or say something to a player, I think, ‘How would I treat my own kid?’ You know what I do best? I’m a great dad. And in a way, that’s the way I coach.”

At the end of the day, I’m in the lobby, waiting for my taxi. Pete is there with me, making sure I get off okay. I realize I haven’t asked him directly how he and the Seahawks found the courage to continue after

he’d made “the worst call ever.” Pete later told

Sports Illustrated

that it wasn’t the worst decision, it was the “worst possible outcome.” He explained that like every other negative experience, and every positive one, “it becomes part of you. I’m not going to ignore it. I’m going to face it. And when it bubbles up, I’m going to think about it and get on with it.

And use it.

Use it!

”

Just before I leave, I turn and look up. And there, twenty feet above us, in foot-high chrome letters, is the word

CHARACTER

. In my hand, I’m holding a bag of blue and green Seahawk swag, including a fistful of blue rubber bracelets stamped in green with

LOB

: Love Our Brothers.

Chapter 13

Chapter 13

CONCLUSION

This book has been about the power of grit to help you achieve your potential. I wrote it because what we accomplish in the marathon of life depends tremendously on our grit—our passion and perseverance for long-term goals. An obsession with talent distracts us from that simple truth.

This book has been my way of taking you out for a coffee and telling you what I know.

I’m almost done.

Let me close with a few final thoughts. The first is that you

can

grow your grit.

I see two ways to do so. On your own, you can grow your grit “from the inside out”: You can cultivate your interests. You can develop a habit of daily challenge-exceeding-skill practice. You can connect your work to a purpose beyond yourself. And you can learn to hope when all seems lost.

You can also grow your grit “from the outside in.” Parents, coaches, teachers, bosses, mentors, friends—developing your personal grit depends critically on other people.

My second closing thought is about happiness. Success—whether measured by who wins the National Spelling Bee, makes it through West Point, or leads the division in annual sales—is not the only thing you care about. Surely, you also want to be happy. And while happiness and success are related, they’re not identical.

You might wonder, If I get grittier and become more successful, will my happiness plummet?

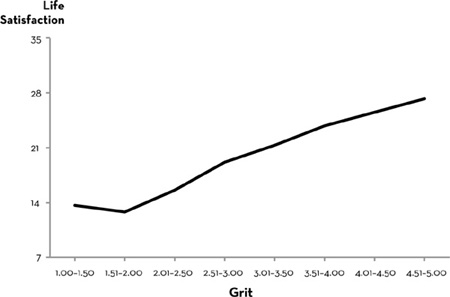

Some years ago, I sought to answer this question by surveying two thousand American adults. The graph below shows how grit relates to life satisfaction, measured on a scale that ranged from 7 to 35 and included items such as, “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing.” In the same study, I measured positive emotions such as excitement and negative emotions such as shame. I found that the grittier a person is, the more likely they’ll enjoy a healthy emotional life. Even at the top of the Grit Scale, grit went

hand in hand with well-being, no matter how I measured it.

When my students and I published this result, we ended our report this way: “Are the spouses and children of the grittiest people also happier?

What about their coworkers and employees? Additional inquiry is needed to explore the possible downsides of grit.”

I don’t yet have answers to those questions, but I think they’re good ones to ask. When I talk to grit paragons, and they tell me how thrilled they are to work as passionately as they do for a purpose greater than themselves, I can’t tell whether their families feel the same way.

I don’t know, for example, whether all those years devoted to a top-level goal of singular importance comes at a cost I haven’t yet measured.

What I

have

done is ask my daughters, Amanda and Lucy, what it’s like to grow up with a gritty mom. They’ve watched me attempt things I’ve never done before—like write a book—and they’ve seen me cry when it got really rough. They’ve seen how torturous it can be to hack away at innumerable doable, but hard-to-do, skills. They’ve asked, at dinner: “Do we

always

have to talk about deliberate practice? Why does

everything

have to come back to your research?”

Amanda and Lucy wish I’d relax a little and, you know, talk more about Taylor Swift.

But they don’t wish their mother was anything other than a paragon of grit.

In fact, Amanda and Lucy aspire to achieve the same. They’ve glimpsed the satisfaction that comes from doing something important—for yourself and others—and doing it well, and doing it even though it’s so very hard. They want more of that. They recognize that complacency has its charms, but none worth trading for the fulfillment of realizing their potential.

Here’s another question I haven’t quite answered in my research: Can you have

too

much grit?

Aristotle argued that too much (or too little) of a good thing is bad. He speculated, for example, that too little courage is cowardice but

too much courage is folly. By the same logic, you can be too kind, too generous, too honest, and too self-controlled. It’s an argument that psychologists Adam Grant and Barry Schwartz have revisited. They speculate that there’s an inverted-U function that describes the benefits of any trait, with the optimal amount being somewhere

between the extremes.

So far, with grit I haven’t found the sort of inverse U that Aristotle predicted or that Barry and Adam have found for other traits, like extroversion. Regardless, I recognize that there are trade-offs to any choice, and I can appreciate how that might apply to grit. It isn’t hard to think of situations in which giving up is the best course of action. You may recall times you stuck with an idea, sport, job, or romantic partner longer than you should have.