Goodbye, Darkness (50 page)

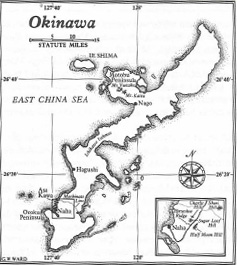

Our voyage to the island was smooth. We read about the natives of Okinawa, a race with mixed Chinese, Malayan, and Ainu blood who buried their ancestors in elaborate stone and concrete tombs. The Japanese had encouraged this custom, our guidebooks said; they could be expected to use these tombs as shelters from artillery fire. (

Not,

I thought,

if I can get there first

.) In their bunks some of the guys read armed services double-columned editions of the classics. Barney and I were absorbed in our endless chess tournament. Others read, wrote letters home, shot the breeze, told sea stories, played hearts, and sang songs based on awful puns: “After Rabaul Is Over,” “Ta-ra-wa-boom-de-ay,” and “Good-bye, Mama, I'm Off to Okinawa.” I didn't feel particularly cheerful, but I do recall a kind of serenity, a sense of solidarity with the Raggedy Asses, which didn't fit with the instinctive aloofness which had been part of my prewar character and would return, afterward, like a healing scar. I had been, and after the war I would again be, a man who usually prefers his own company, finding contentment in solitude. But for the present I had taken others into my heart and given of myself to theirs. This was especially true in combat. Once, when we were treated to the exquisite luxury of riding to the front in six-by trucks (six wheels, six-wheel drive), I was seized by a compelling need to empty my bowels. Just then the line of trucks stopped while the lead driver negotiated a way around a fallen tree, and I took advantage of the pause to leap out and squat in full view of a company of Marines. At the critical moment, all the truck motors started up, and I yelped, “Wait for me!” I finished the job with one convulsion and sprinted back in time, pulling up my pants as all hands cheered. Before the war I wouldn't have dreamt of hurrying so personal an errand, let alone carrying it out in the full view of strangers. But it was essential then that I not be left behind by the Raggedy Ass Marines. I had to be with my own people. Like Saul on the road to Damascus, I had entered the true fold by turning all of my previous customs on their heads. I had no inkling then of how vincible that made me, how terrible was the price I might have to pay. Yet as a Christian I should have known how vulnerable love can be.

Holy Week ended on Saturday, March 31, when the fleet anchored off western Okinawa. We were awakened in the night by the shattering crash of broadsides from over a thousand Allied warship muzzles — the Royal Navy was there, too — and like the virtuous woman in the Proverbs, we rose while it was not yet light, worked willingly with our hands, squaring away our gear, and ate not the bread of idleness. We did, however, eat. Indeed, feast might be a better word. We lined up in the murky companion ways for the only decent fare I ever saw on a troop transport: steak, eggs, ice cream, and hot coffee. I remember wondering whether this would be my last meal. This Easter happened to be my twenty-third birthday. My chances of becoming twenty-four were, I reflected, very slight. None of us, of course, had heard anything about the atomic bombs, then approaching completion. We assumed we would have to invade Kyushu and Honshu, and we would have been unsurprised to learn that MacArthur, whose forecasts of losses were uncannily accurate, had told Washington that he expected the first stage of that final campaign to “cost one million casualties to American forces alone.” All we could be sure of was that Okinawa was to be the last island before that climax, and that the enemy would sacrifice every available man to drive us off it.

At 4:06

a.m

. Admiral Turner's flagship signaled: “Land the Landing Force.” We saddled up in darkness, groaning under the weight, and waited by the cargo nets, watching shells burst on a beach we could not yet see. Then dawn came rapidly, so fast you could almost watch it travel across the water. In the first dim light I could see that there was land there; there were clouds on the horizon and then a denser mass that was shapeless beneath the clouds. As the first shafts of sunlight arrived the mass became lettuce green, an isle floating in a misty haze, and in the distance you could see the torn, ragged edges of the ridges supporting the rice terraces. I hadn't expected such vivid colors. All the photographs I had seen had been black-and-white.

Now we descended the ropes into the amphtracs, which, fully loaded, began forming up in waves. Yellow cordite smoke blew across our bows, battleship guns were flashing, rockets hitting the shore sounded

c-r-r-rack,

like a monstrous lash, and we were, as infantrymen always are at this point in a landing, utterly helpless. Then, fully aligned, the amphtracs headed for the beach, tossing and churning like steeds in a cavalry charge. Slowly we realized that something we had anticipated wasn't happening. There were no splashes of Jap mortar shells, no roars of Jap coastal guns, no grazing Jap machine-gun fire. The enemy wasn't shooting back because, when we hit the beach at 8:27

a.m

., there wasn't any enemy there. It was an unprecedented stratagem — the greatest April Fool's Day joke of all time. Sixty thousand of us walked inland standing up and took Yontan (now Yometan) and Kadena airfields before noon. A Japanese fighter pilot landed on Yontan, climbed down, and ordered a tank of gas in Japanese before he realized something was wrong. He reached for his pistol and was gunned down before he could touch the butt. Idly exploring the quaint, concrete, lyre-shaped burial vaults built on the slopes of the low hills, we felt jubilant. In our first day we had established a beachhead fifteen hundred yards long and five thousand yards deep. None of us could have known then that the battle would last nearly three months, becoming the bloodiest island fight of the Pacific war; that over 200,000 people would perish; that Ernie Pyle, the famous war correspondent just arrived from the ETO, would be killed on Ie Shima; and that both Buckner and Mitsura Ushijima, the Japanese general, would be dead before the guns were silenced.

There was an omen, had we but recognized it. At 7:13

p.m

. a kamikaze dove into the

West Virginia,

erupting in flame. That should have been the tip-off to the enemy's strategy: sink the ships, isolating the Americans ashore. Ushijima had 110,000 Nips of his Thirty-second Army, all Manchurian veterans, concentrated in the southern third of the island. Tokyo's high command had decided to make Okinawa the war's greatest Gethsemane, another Iwo but on a much grander scale. The Americans would be allowed “to land in full” and “lured into a position where they cannot receive cover and support from the naval and aerial bombardment.” Because of the tremendous U.S. commitment, there would be ten American soldiers for every foot of ground on Okinawa's lower waist, where Ushijima planned to make his stand. Thus wedged together, they would be like livestock in a slaughterhouse. Ushijima had studied the cable traffic from Iwo in its last days. Curiously, he found it encouraging. Pillboxes and blockhouses had been built here, too; but in addition, massive numbers of caves masked heavy artillery which could be rolled out on railroad tracks, fired, and rolled back in. Naha had been the site of Japan's artillery school for years. Every gully, every crossroads, every ravine in the south had been pinpointed by the defenders. It would be like an enemy attack on American infantry at Fort Benning. The Japs could target each shell within inches. Under these circumstances, Ushijima reasoned, Buckner's army could be “exterminated to the last man.”

The Allied fleet, in this scenario, would be wiped out by the kamikazes. Even before L-day, these human torpedoes had begun their destruction of our ships. Zeroes, Zekes, Bettys, Nicks, Vals, Nakajimas, Aichis, Kagas — virtually every Nip warplane that could fly was loaded with high explosives and manned by pilots, some mere teenagers, who would dive to their deaths and take sinking Allied warships with them. In the Philippines, in the early stages of this airborne hara-kiri, fliers had operated individually. Now the American and British seamen would confront massed suicide attacks called

kikusui

, or “floating chrysanthemums.” Ultimately they failed, but anyone who saw a bluejacket who had been burned by them, writhing in agony under his bandages, never again slandered the sailors who stayed on ships while the infantrymen hit the beach. Altogether, Nippon's human bombs accounted for 400 ships and 9,724 seamen — a casualty list which may be unique in the history of naval warfare.

Our first night ashore was interrupted only by fitful machine-gun bursts and the

wump-wump-wump

of small mortars — there were a few Japs beyond our perimeter, left behind for nuisance value — and during morning twilight, after breakfasting on K rations, we NCOs shouted, “Route march, ho!” starting the long push northward, the Marines loping along in the unmistakable gait of the infantryman, our muscles feeling as though they had been pulled loose from the joints and sockets they were supposed to control. In those first days we covered about twenty miles a day, an ordeal, since we were carrying all our equipment, but we were young and grateful to be still alive. The scenery was lovely. To the left lay the sea; to the right, the hills rose in graceful terraces, each supporting rice paddies. Our path was of orange clay, bordered by stunted bushes and shrubs, cherry trees, and red calla lilies; I had never seen red ones before. Even the remains of the bridges, which had been taken out by our bombers, were beautiful. The Okinawans, like the Japanese, believe that straight lines are harsh, while curved lines suggest serenity, and the sinuosity of these arches conveyed a calm and repose wholly irrelevant to, and superior to, our mission here. Especially was this true when we rounded a curve and beheld, on the beach, the sprawled body of a girl who had been murdered. I had never seen anything like that. The thought that an American man could commit such a crime in fighting a just war raged against everything I believed in, everything my country represented. I was deeply troubled.

Northern Okinawa, we found, was not defenseless. Motobu Peninsula, steep, rocky, wooded, and almost trackless, was dominated by two mountains, Katsu and fifteen-hundred-foot, three-crested Yaetake. Entrenched on Yaetake were two battalions under the command of a tenacious officer, Takehiko Udo. In the ensuing battle the Sixth lost 1,304 men, among them Swifty Crabbe, who took a rifle bullet below his right elbow which severed a nerve, rendering his thumb uncontrollable — a ridiculous wound, but he was delighted to leave the island. To these casualties must be added the professional reputation of our redundant commanding officer, Colonel Hastings, who was fired in the middle of the fight. I was present at the dramatic moment. Lem Shepherd, the divisional commander, asked where the regiment's three battalions were, and the Old Turk, highly agitated, confessed that he wasn't aware of, familiar with, or apprised of where nearly three thousand men might be located, found, or situated. So Shepherd sent him back to the rearest echelon and appointed Colonel William J. Whaling as our new CO. Whaling had fought well on the Canal; we had confidence in him.

And our confidence in ourselves was growing. The Raggedy Asses were always in their element off parade, with no saluting and little sirring, unshaven and grimy in filthy dungarees, left to do what they did best: use their wits. There was no role here for mechanized tactics; tanks were useful only for warming your hands in their exhaust fumes. This was more like French and Indian warfare. Each of us quickly formed a map of the peninsula in his mind; we knew which ravines were swept by Nambu fire and how to avoid them. (Beau Tatum was the exception. His sense of direction, or rather the lack of it, was still uncanny. If a company had let Beau direct them, they would have wound up on Iwo Jima.) Much of the time I kept the battalion situation map, drawing red and blue greasepaint arrows on Plexiglas to show, respectively, what the Japs and our forces were doing. The genial operations officer, an Irish major from the Bronx, never pulled rank on me, though he must have been tempted. It was interesting work; better still, it was comparatively safe. Unfortunately Krank found another job for me. Shepherd planned a viselike compression, an elaborate envelopment, with the Fourth Marines assaulting the face of Yaetake while we in the Twenty-ninth attacked the rear. A patrol was needed to link up the two regiments. The Raggedy Asses, it was decided, would provide the four-man patrol. Their craven sergeant was ordered to lead it.

I took Knocko, Crock, Pisser, and Killer Kane because they were immediately available and the afternoon was waning. The veins and arteries of the dying day streaked the horizon over the East China Sea. My throat was thick with fear. We moved silently down the path, half crouched, passing Japanese corpses on both sides, any of which could be shamming. Darkness began to gather. Now I was more worried about the Fourth Marines than the enemy. Because the Nips were so skillful at infiltration, the rule had been established that after night had fallen, no Marine could leave his foxhole for any reason. Anyone moving was slain. Two nights before, a man in our battalion had been drilled between the eyes when he rose to urinate. So I moved along the path as quickly as I could, and I recall ascending a little wiggle in the trail, turning a corner, and staring into the muzzle of a Browning heavy machine gun. “Flimsy,” I said shakily, giving that day's password. “Virgin,” said the Fourth Marines' gunner, giving the countersign. He relaxed and reached for a cigarette. He said, “You heard the news? FDR died.” I thought:

my father.