Goodbye, Darkness (47 page)

My arrival in Tacloban is both spectacular and disconcerting. At President Marcos's insistence, I am once more ensconced in a gleaming limousine, part of a cavalcade flanked by motorcycle outriders. Sirens scream again; red lights flash; a phalanx of Philippine generals and high officials accompanies me at every stop. The explanation, which I demand, is that guerrillas and Moro secessionists lurk in the rice paddies and among the hillocks in the countryside. That is hardly satisfactory for a knee-jerk FDR liberal, but I have no alternative. In time we draw up to the Price house under a hurriedly erected sign whose paint is still wet:

distinguished visitors — welcome to leyte

. The building is imposing, of white stucco with green trim surrounded by a fence of painted Marsden matting. It is also unoccupied. Until recently the mansion housed the offices of a Regional National Economic Development Authority — whatever that was; I am just reading my notes — and before that it was a school: “Notice: Undergraduate Students Are Not Allowed to Make a Research Here,” reads a mysterious warning on one door. But none of the subsequent occupants have removed evidence of the Japanese determination to kill MacArthur here. Walls are pocked and pitted by machine-gun bullets, one wall is marred by a hole made by a 20-millimeter shell, and a .50-caliber slug is still embedded in plaster above the bed in which the general slept.

Outside, the brooding mass of Samar is visible on the left; Leyte's Red Beach is a short stroll from here, and I and my mob head for it. Various signs accost me along the way: the delights of San Miguel beer are described; a beverage called Miranda is advertised as “the Sunshine Drink”; Coke and Pepsi are available (“Have a Pepsi Day”); and a placard urges us to buy “Unisex Fashions,” though how such clothing could achieve popularity in one of the world's most male chauvinistic countries I do not know. Presently the landscape becomes more attractive. Straw huts are tidy and picturesque, the shrubbery is riotously green, and amid its waxen leaves you see the red flowers of

santan

and the white blossoms of the

Doña Aurora,

named for the widow of Manuel Quezon, the Philippines' George Washington.

In a vast reflecting pool stand statues of MacArthur and the six men who trudged ashore with him. They are depicted exactly as they were in the famous photograph, but each is twice life-size. A three-tiered memorial carries inscriptions from the general's invasion speech and a tribute from Marcos. There is one peculiar error. MacArthur's collar bears five-star ornaments, but he didn't achieve five-star rank until December 16, 1944, nearly two months after he waded in. It is a small slip; pointing it out to my hosts now would be needlessly rude. Instead, I turn to a four-and-a-half-foot seawall beneath which the surf laps listlessly. I bound down. There can be no doubt that I am where I mean to be. The temptation to plunge in is irresistible. I wade out and back; the spectators, including several small children from the huts, watch solemnly, almost standing at attention. This ground is sacred to them. Like the Guamanians, they celebrate Liberation Day every October 20 by reenacting MacArthur's return with landing craft and fireworks simulating shellfire. In 1969, the twenty-fifth anniversary, they even dropped paratroopers. To me, however, peeling off my socks and wringing them out, the experience is flat. Unlike my feelings on the shores of the Canal and Tarawa, I cannot identify with what happened here — cannot re-create it because I neither served here nor knew anyone who did. And my well-meaning escorts are no help. You cannot evoke the past in a crowd. I need solitude.

The author at Leyte, where MacArthur waded ashore

The Filipino monument to MacArthur's landing party

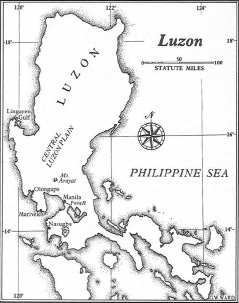

But I am not going to get it, not on this trip. By motorcade and then by air I am borne to Lingayen Gulf, 450 miles closer to Japan and thirty-five years after MacArthur landed here on Luzon and opened his drive toward Manila. In addition to my retinue, all the local officials turn out to welcome me — one suspects that Marcos would have their heads if they didn't — and after ceremonial bows and murmured greetings, we stroll along a strip of beach, though not all of it. This incomparable shore goes on and on, 124 miles of it, as though New York's Jones Beach extended southward to Wilmington, or Malibu Beach to San Diego. For the historian, however, the chief spectacle is near a monument to MacArthur's landing of January 10, 1945. Passing a graceful promenade, I stumble upon

dalakorak,

small creeping vines that seem to be underfoot everywhere, and come upon a playground. How often on this trip I have seen children romping beneath silent guns, I think, and how splendid a tribute that is. Rehearsing his invasion speech the night before the Leyte landing, the general had anticipated “the tinkle of the laughter of little children returning to the Philippines.” His outspoken physician had said, “You can't say that.” MacArthur said, “What's the matter with it?” The doctor said, “It stinks. It's a cliché.” The general muttered but crossed it out. One wishes he had found another way of saying it. Continuity of the generations is, after all, the only bright sequel to war.

The general would have preferred to come ashore on Luzon almost anywhere but here. As early as 1909 an American writer had predicted that any invader of the island would have to hit Lingayen first. This was where Homma's Japanese had debarked on the fifteenth day of the war. MacArthur valued surprise, usually above all else, but after studying a half-dozen other beaches and searching his memory — he had first served in the Philippines forty-two years earlier — he reluctantly returned to this one. There was just no other way of manipulating the enemy into a series of intricate maneuvers, where MacArthur's prodigious gifts could soar, on the Central Luzon Plain. You needn't be a strategist or even like the man (he wasn't very likable) to appreciate his subsequent feats there. His reconquest of Luzon was awesome. And the Filipinos were jubilant. They already knew of his triumph on Leyte. From the moment he landed at Lingayen and began moving inland by jeep, they decked the jeep with flowers, like a Roman chariot. They kissed his hand, pressed wreaths around his neck, and tried to touch his uniform.

This performance could have been shattered had Yamashita, who had become the legendary “Tiger of Malaya” in the opening weeks of the war, chosen to contest the beachhead. But drained of his best men on Leyte, where Tokyo had ordered him to fight despite his misgivings, he knew he could not expose his Luzon force to U.S. naval gunfire. Instead, he withdrew into the mountains, awaiting his opportunity to descend onto the central plain, the amphitheater both commanders needed to grasp the rainbow's end at the bottom of it: Manila. But the Tiger's chance never came. In a series of lightning thrusts MacArthur invested Clark Field, landed a corps above Bataan, took the invaluable port of Olongapo, put a regiment ashore at Mariveles, seized Nasugbu, south of Manila, without losing a man, and lost just 210 men in overpowering the 5,200 Japanese on Corregidor by landing an airborne regiment on Topside while an infantry battalion, with exquisite timing, leaped from Higgins boats to storm the Bottomside shore. Manila was virtually surrounded. The Tiger had been denied an opportunity to show his claws. He was trapped in a double envelopment, isolated and impotent. In the Pentagon George Marshall, who detested MacArthur personally, was rhapsodic. The outcome was, in fact, unparalleled in modern warfare. Never had such masses of superbly disciplined soldiers been so completely outwitted, foiled, and surpassed on every level. The most gifted officer Hirohito could put in the field was left with his army, tons of equipment — and no one to fight.

Yet every judgment of MacArthur, praising him or blaming him, has to be qualified. Flying in our small plane from Lingayen and its charming playground to Manila, we follow the same route taken by the Japanese Mitsubishi bombers in December 1941, nine hours after Pearl Harbor, when, incredibly, MacArthur's air force was caught on the ground at Clark Field and destroyed. Off the star-board bow lies Mount Arayat, once a stronghold of the Hukbalahaps, the Huk guerrillas who had fought the Japanese occupiers so steadfastly and were so shamefully ignored when the general restored power to the Spanish aristocrats, despite the fact that the most prominent of them had spent the past three years collaborating with the enemy. As we descend for our landing on what was once Nichols Field and is now Luzon's chief airport, the low-slung mountains of Bataan and the placid waters of the bay, with Corregidor at its neck, are on our right. I wonder whether the Mitsubishi pilots noticed them on that first morning of the war and pondered their military significance.

In the 1930s Japanese officers, disguised as bicycle salesmen, sidewalk photographers, and assorted tradesmen, appeared in the archipelago to survey Philippine defenses. Today 80 percent of the islands' tourists are Japanese, but here, as in the Marianas, this is another era; the tourist ministry estimates that three couples out of every four are honeymooners. The Manila they see is not prewar Manila. That city was virtually destroyed in 1945. Yet some landmarks remain. The ageless, gargantuan rubber tree still stands in front of the Army Navy Club. No. 1 Victoria Street, MacArthur's prewar headquarters, has vanished, and the Manila Hotel, just across the street, was leveled by the Japanese near the end of the war when MacArthur was within sight of it and preparing to retake it. Its facade was preserved, however, and a new hotel has been built on the site of the old one, with a MacArthur penthouse on top. Sugar and rice barges continue to drift between the ancient gray stone walls on either bank of the Pasig River, and on the shores jitneys weave in and out of the heavy traffic. Periodically Marcos threatens to abolish the vans, but they perform a useful service, skillfully cutting in and out of the flow of cars. Auto density is very high; Manila's population is now over seven million.

Both foreigners and Filipinos are drawn to the city's magnet for sightseers: Intramuros, the old walled city, with Fort Santiago and San Augustine Church within it. No one knows the exact age of Intramuros, but Magellan arrived in 1521, the Spaniards founded Manila in 1572, and everything within the ancient city had been built by the turn of that century, nearly four hundred years ago. In their last, drunken orgy of destruction, the Japanese tried to reduce Intramuros to ruins, but it was impossible; the stone walls are nineteen feet high and more than twice that thick. At one time they shielded within their triangular perimeter six churches and monasteries, hanging gardens, inner courts, and a maze of cobblestoned streets. Most of that is gone, though the Augustine church still stands as it did when the Nipponese used most of Intramuros for barracks and shawled Filipino women prayed in the church's pews for the safety of their sons, fighting in the guerrilla bands in the hills. Today lovers embrace in dark corners. Outside, one is depressed to see frolicking boys playing war with toy pistols.

As in most countries outside North America and Western Europe, the gap between rich and poor here boggles the mind. It shocks American newcomers, who do not grasp that anything above bare subsistence for the masses hardly exists outside Western Europe and their own fortunate oasis. Most wealthy Filipinos live in Manila's Makati district, in sprawling villas hidden by ivy-covered walls, each with its private police force and snarling Dobermans. In many ways Makati is redolent of San Juan's Condato, or Nassau's Lyford Cay. The average Filipino earns a few pesos, less than a dollar, a week. In Makati, a patrician bride may spend twelve thousand dollars for her wedding dress. Polo is a popular sport among the oligarchy, and although newspapers report some of the conspicuous consumption of the few, the many are not mutinous. Marcos does suppress news of the most shocking extravaganzas. “We're too close to the flames,” he says elliptically, “to play with fire.” Perhaps the most striking evidence of upper-class dominance is the presence of the military cemetery in their midst. Surrounded by the mansions of the aristocracy, the white crosses in Makati rise and fall, in rhythmic undulations of the rolling topsoil, like whitecaps fixed in time. Even the dead belong to the opulent. But the ironies of the Pacific war are endless. Riding up to my room in the rebuilt Manila Hotel that evening, I glance casually at the elevator's control panel. It bears the name of the manufacturer: Mitsubishi.