Golden (46 page)

Authors: Jeff Coen

A nervous and sweating Chris Kelly in the lobby of the Dirksen US Courthouse, the same day he first attempted suicide.

REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION OF

CHICAGO TRIBUNE.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Robert Blagojevich at the federal courthouse.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

The prosecution team (from left): Carrie Hamilton, US Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald, Reid Schar, and Chris Niewoehner

REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION OF

CHICAGO TRIBUNE.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

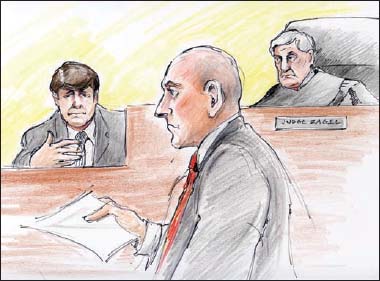

A court sketch of Blagojevich testifying under cross-examination by Reid Schar, as US District Judge James Zagel looks on.

COURTESY OF ANDY AUSTIN

Endgame

They arrived for the meeting early. Dew still rested on the windshields of the cars parked along quiet Ravenswood Avenue in front of the old brick industrial building that housed the Friends of Blagojevich headquarters.

Dressed in jeans, a white T-shirt, and a baggy black golf pullover, John Wyma parked his car down the street and hustled toward the front door of 4147 North. Lon Monk, also in jeans, pulled his Volkswagen SUV into a spot directly across the street from the four-story building with the red-brick facade. Both men climbed three flights of stairs for their meeting with Rod Blagojevich.

October 22, 2008, was a crisp autumn day in Chicago. Trucks dropped off piles of dirty clothes for cleaning next door at a uniform-rental business. Commuters made their way to the nearby CTA train station.

Ninety minutes after he arrived, Wyma emerged by himself. Grasping a piece of paper and a Blackberry in his left hand, he headed toward his car. The last thing he was expecting was a pair of newspaper reporters and a photographer. He looked stunned. His eyes widened and he stopped cold, glancing to his left and right as if looking for an escape. But he was trapped.

The

Tribune

reporters were there seeking his reaction to being named in a new subpoena issued by a federal grand jury, one that was interested in his work for Provena Health some years before. Still standing in the middle of Ravenswood Avenue, Wyma turned and took a few steps toward the political offices. Perhaps worried how bad it would look for him to run back into

the headquarters, Wyma turned around again and walked quickly toward his car.

“I have no comment,” he mumbled, before he disappeared.

Wyma had done his best to keep a swirl of emotions suppressed. Just days earlier, he had become what amounted to the last domino falling in Blagojevich's line of defense against the federal government.

In September, he had immediately suspected Rezko when he got the subpoena. A grand jury wanted to know about his dealings as a lobbyist with Provena Health, a hospital and medical center group he had worked with in 2004, when the company was trying to get approval for a heart surgery facility in Elgin. Back then, two years into the first Blagojevich administration, dealing with that board meant Rezko, and it meant Stuart Levine. Often it meant money moving to Blagojevich's campaign fund before things loosened up and proposals could get by the board. Provena had gotten its approval, and its political arm had made a $25,000 donation to the governor weeks later.

Wyma couldn't have known all that Rezko had told authorities by the time October had rolled around, but his suspicions were right.

After weeks of testimony from Levine and others, Rezko had been convicted of money laundering, fraud, and aiding bribery in his own case that summer, and the trial had lasted long enough for prosecutors to flip men like Ali Ata, who testified about giving the governor the $25,000 check and getting a big state job.

And facing mounting pressure and a long prison term, Rezko could no longer afford not to cooperate, despite such resistance being ingrained in his very nature. Perhaps no one in Blagojevich's inner circle had been as mentally tough as Rezko, but even he had his limits. Pressure from prosecutors and his family had begun to mount. He had been loyal to the end, even through a criminal trial that had ended badly for him, and where had it gotten him? His family thought enough was enough. No one had helped him when he needed it most. Rezko began talking with his lawyer, Joe Duffy, about what cooperating with the feds would mean. He had gotten a further wakeup call from prosecutors in his early meetings with them. If he ever wanted to see his family again outside a prison visiting room, he needed to tell them the truth about his past, holding nothing back.

Before Rezko's decision, the investigation officially known as Operation Board Games was running out of string. Decisions had been made inside the FBI to run things out as best they could, but there wasn't much traction.

Supervisors thought there were plenty of arrows pointing to Blagojevich, and cases had been made all around him, but there wasn't enough evidence on him specifically. Some thought a possible route was investigating money that had been given to Patti Blagojevich by Rezko's company, a strategy some called “balls to the wall on Patti,” but that wasn't a sure thing.

Enter Rezko. By July, he was in full discussions with prosecutors, and a new avenue was opening. Rezko was talking about his history with Blagojevich and his role in the machinations inside the governor's administration. In the beginning, Blagojevich had come to him three times seeking his help. Rezko had said no each time, he explained, before he had eventually decided he could help Blagojevich navigate the political waters of Illinois. If Rod wouldn't pull out of the race, Rezko told his new friend, he wouldn't pull out either.

Rezko, who had dealt with Republicans in the Edgar, Thompson, and Ryan administrations, knew that meant going to Bill Cellini, who had been entrenched with some of the same players for decades. Cellini was going to have a new political boss, Rezko told him. His name was Rod Blagojevich. He was going to win the election, and Cellini was going to be able to work with him.

Meanwhile, Rezko had become deeply involved in Blagojevich's campaign. He was responsible for bringing in millions, and after Blagojevich was elected, Rezko acknowledged he was among those trusted to name people to boards and commissions in the state. He had turned his actual power into even more power, knowing that appearances often were as good as reality. Blagojevich had known of many of his ideas in general and endorsed them, Rezko told prosecutors, but wasn't always up on the details. It was widely believed that Rezko had the governor's ear. And while he did, Rezko used his position as well. There had been times when he would tell people to do things, he said, knowing they wouldn't check with the governor.

Rezko's version of events was that he had outlined broad strategies for making money through Blagojevich's official actions and that he had shared these with Monk, Chris Kelly, and the governor. Any money that was brought in was to be paid to all of them in the future. Rezko told prosecutors he kept a kind of marker in his head of what everyone might be owed. But by and large, there was no real method to the madness and no money to divide. Dollars that Rezko brought in he often used himself. When he pulled corrupt money out of state deals, he had used it in a shell game to move cash around and cover his own business losses.

Rezko discussed a lot of politicians, including dealings with former governors and Obama. He had been a fundraiser for many, a fixer for others, and a trusted ear. But prosecutors and the FBI were not completely impressed with what he delivered. Rezko did say he knew that Chris Kelly had told Blagojevich about the effort to get campaign money from film producer Tom Rosenberg and said he then checked with Blagojevich himself about holding up the TRS investment with Rosenberg's firm. But at times there were frustratingly few details, as if Rezko were holding back. Chiefly, Rezko withheld that he actually had paid cash to one member of Blagojevich's inner circle, Lon Monk.

Other times Rezko absolutely refused to agree with some of what Levine had said against him at his trial. Rezko would serve the rest of his life in prison, it seemed, before lining up behind everything that Levine had said. That didn't make Rezko a promising witness, and neither did a letter he had written to the judge in his case, Amy St. Eve, complaining months earlier that the government was pressuring him to lie about Blagojevich and Obama. Some investigators thought Rezko might have had the ability to deliver the dagger they needed on Blagojevich, and his sentencing was delayed again and again as he worked with them, but he just wasn't providing a finishing blow.

Still, there were some interesting things Rezko had said that moved the investigation forward. Among them was that he'd had conversations with Wyma about what it would take to move a plan through the Illinois Health Facilities Planning Board years before. Rezko said Wyma had gone to Monk first asking what to do and had been pointed in Rezko's direction. Rezko said he had communicated the going rateâmeaning how much it would costâ and told Wyma there was a dispute between one member of the IHFPB and Provena. The government eventually would contend they could not substantiate Rezko's claim that he had communicated a dollar amount to Wyma, but they had never approached Wyma about his Blagojevich connections, despite his history as a Blagojevich staffer in Washington and as a lobbyist.

Because of Rezko, Wyma wound up as a subpoenaed subject of the government's investigation, and through his lawyer, Zachary Fardon, set up a date to have a preliminary talk with prosecutors about his past and what they were looking for.

In the meantime, Wyma had a pair of fund-raising meetings set up with Blagojevich, including on October 6, at the Friends of Blagojevich offices. The governor told Wyma about a plan to expand the Illinois Tollway. He

was going to roll out his proposal slowly, teasing the road builders with a $1.8 billion program, with the promise of another much larger plan. He wanted to see what the group might give to his campaign fund by the end of the year, Blagojevich said. “And if they don't perform, fuck âem.”

Meeting later with Wyma and the governor that day was one of Wyma's clients, Michael Vondra, a construction executive in the asphalt business. Vondra was looking at a deal for one of his companies with British Petroleum for a distribution center in Chicago's south suburbs and wanted Blagojevich to get behind the idea and smooth things out with state regulators. Blagojevich thought it was a great idea but had more to say after Vondra left the meeting. Wyma should ask his client for $100,000 in campaign money for the governor by the end of 2008.