Going Solo (11 page)

Authors: Roald Dahl

There was only one runway on the little Nairobi aerodrome and this gave everyone plenty of practice at cross-wind landings and take-offs. And on most mornings, before flying began, we all had to run out on to the airfield and chase the zebras away.

When flying a military aeroplane, you sit on your parachute, which adds another six inches to your height. When I got into the open cockpit of a Tiger Moth for the first time and sat down on my parachute, my entire head stuck up in the open air. The engine was running and I was getting a rush of wind full in the face from the slipstream.

‘You are too tall,’ the instructor whose name was Flying Officer Parkinson said. ‘Are you sure you want to do this?’

‘Yes please,’ I said.

‘Wait till we rev her up for take-off,’ Parkinson said. ‘You’ll have a job to breathe. And keep those goggles down or you’ll be blinded by watering eyes.’

Parkinson was right. On the first flight I was almost asphyxiated by the slipstream and survived only by ducking down into the cockpit for deep breaths every few seconds. After that, I tied a thin cotton scarf around my nose and mouth and this made breathing possible.

I see from my Log Book, which I still have, that I went solo after 7 hours 40 minutes, which was about average. An RAF pilot’s Log Book, by the way, is, or certainly was in those days, quite a formidable affair. It was an almost square (8” × 9”) book, 1” thick and bound between two very hard covers faced with blue canvas. You never lost your Log Book. It contained a record of every flight you had ever made as well as the plane you were flying, the purpose and destination of the trip and the time you had spent in the air.

After I had gone solo, I was allowed to go up alone for much of the time and it was wonderful. How many young men, I kept asking myself, were lucky enough to be allowed to go whizzing and soaring through the sky above a country as beautiful as Kenya? Even the aeroplane and the petrol were free! In the Great Rift Valley the big game and smaller game were as plentiful as cows on a dairy farm, and I flew low in my little Tiger Moth to look at them. Oh, the animals I saw every day from that cockpit! I would fly for long periods at a height of no more than sixty or seventy feet, gazing down at huge herds of buffalo and wildebeest which would stampede in all directions as I whizzed over. From an illustrated book I had bought in Nairobi, I learnt to recognize kudu,

Thomson’s gazelle, eland, impala and many other animals. I saw plenty of giraffe and rhino and elephant and lion, and once I spotted a leopard, sleek as silk, lying along the trunk of a large tree. He was watching some impala grazing below him and deciding which one to have for his dinner. I flew over the pink flamingos on Lake Nakuru and I flew all the way round the snow summit of Mount Kenya in my trusty little Tiger Moth. What a fortunate fellow I am, I kept telling myself. Nobody has ever had such a lovely time as this!

The initial training took eight weeks, and at the end of it we were all fairly competent fliers of light single-engined aircraft. We could loop the loop and fly upside down. We could get ourselves out of a spin. We could do forced landings with the engine cut. We could side-slip and land decently in a strong cross-wind. We could navigate our way solo from Nairobi to Eldoret or Nakuru and back with plenty of cloud about, and we were full of confidence.

As soon as we had passed out of Initial Training School in Nairobi, we were put on a train bound for Kampala, in Uganda. The journey took a day and a night, and the train was so slow that we spent a lot of the time, frisky youngbloods that we were, climbing up on to the roofs of the carriages and running the whole length of the train and back, jumping over the gaps between the carriages.

At Kampala there was an Imperial Airways flying-boat moored on the lake and waiting to take the sixteen of us 2,000 miles north, to Cairo. By now we were half-trained pilots and wherever we went we were treated as moderately valuable properties. We ourselves were bursting with energy and exuberance and perhaps a touch of self-importance as well because now we were intrepid flying men and devils of the sky.

Nairobi

18 December 1939Dear Mama,

Well, everything here is also going very smoothly. I did my first solo flight some days ago and now go up alone for longish periods every day. I’ve just learnt to loop the loop and spin and the next thing we’ve got to do is flying upside down, which isn’t quite so funny. But it’s all marvellous fun …

The great flying-boat flew low for the whole of the long journey, and as we passed over the wild and barren lands where Kenya meets the Sudan we saw literally hundreds of elephant. They seemed to move around in herds of about twenty, always with a mighty bull tusker leading the herd and with the cows and their babies in the rear. Never, I kept reminding myself as I peered down through the small round window of the flying-boat, never will I see anything like this again.

Soon we found the upper reaches of the Nile and followed it down to Wadi Halfa, where we landed to refuel. Wadi Halfa then was one corrugated-iron shed with a lot of 44-gallon drums of petrol lying around, and the river was narrow and very fast. We all marvelled at the skill of the pilot as he put the great lumbering flying-machine down on that rushing strip of water.

In Cairo we landed on a very different Nile, wide and sluggish, and we were shuttled ashore and taken to Heliopolis aerodrome and put on board a monstrous and ancient transport plane whose wings were joined together with bits of wire.

‘Where are they taking us to?’ we asked.

‘To Iraq,’ they answered, ‘and jolly good luck to you all.’

‘What do you mean by that?’

‘We mean that you are going to Habbaniya in Iraq and Habbaniya is the most godforsaken hell-hole in the entire world,’ they said, smirking. ‘It is where you will stay for six months to complete your advanced flying training, after which you will be ready to join a squadron and face the enemy.’

Unless you had been there and seen it with your own

eyes you could not believe that a place like Habbaniya existed. It was a vast assemblage of hangars and Nissen huts and brick bungalows set slap in the middle of a boiling desert on the banks of the muddy Euphrates river miles from anywhere. The nearest place to it was Baghdad, about 100 miles to the north.

Habbaniya

20 February 1940Dear Mama,

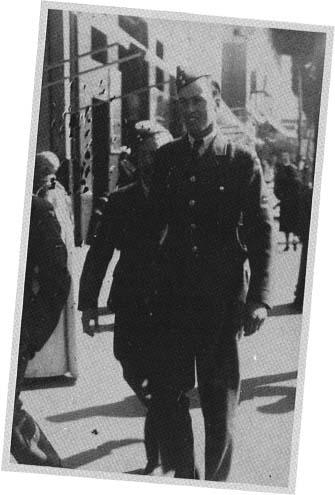

Here is a not very good photo taken of me in the streets of Cairo by one of those men who pop up from behind a public lavatory and snap you and hand you a bit of paper telling you to call tomorrow for the print …

This amazing and nonsensical RAF outpost was colossal. It was at least a mile long on each of its four sides, and there were paved streets called Bond Street and Regent Street and Tottenham Court Road. There were hospitals

and dental surgeries and canteens and recreation halls and I don’t know how many thousands of men lived there. What they did I never discovered. It was beyond me why anyone should want to build a vast RAF town in such an abominable, unhealthy, desolate place as Habbaniya.

Habbaniya

10 July 1940Dear Mama,

We’ve been here nearly 5 months now, and as we get nearer and nearer to the time when our course is finished and we go elsewhere we get more and more thrilled. It will be curious to see ordinary men and actual women doing ordinary things in ordinary places once more, to call a taxi or use the telephone; to order what you want to eat or to see a train; to go up a flight of stairs or see a row of houses. All these things and many more I shall derive the very greatest pleasure from doing …

At Habbaniya we flew from dawn until 11 a.m. After that, as the temperature in the shade moved up towards 115ºF, everyone had to stay indoors until it cooled down again. We were flying more powerful planes now, Hawker Harts with Rolls-Royce Merlin engines, and everything became suddenly much more serious. The Harts had machine-guns on their wings and we would practise shooting down the enemy by firing at a canvas drogue towed behind another plane.

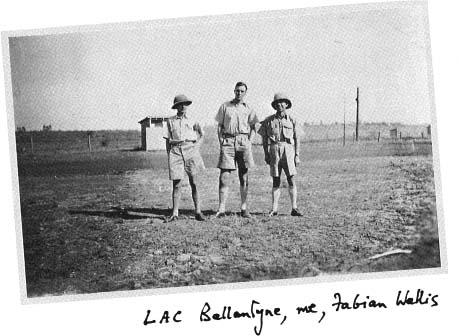

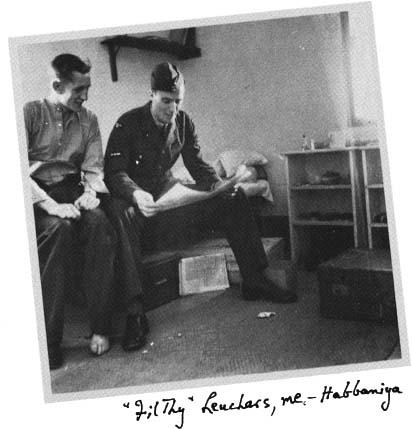

My Log Book tells me that we were at Habbaniya from 20 February 1940 to 20 August 1940, for exactly six months, and apart from the flying which was always exhilarating, it was a pretty tedious period of my young life. There were minor excitements now and then to relieve the boredom such as the flooding of the Euphrates when we had to evacuate the entire camp to a windswept plateau for ten days. People got stung by scorpions and went into hospital for a while to recover. The Iraqi tribesmen sometimes took pot shots at us from the surrounding hills. Men occasionally got heatstroke and had to be packed in ice. Everyone suffered from prickly heat and itched all over for much of the time.

But eventually we got our wings and were judged ready to move on and confront the real enemy. About one half of the sixteen of us were given commissions and promoted to the rank of Pilot Officer. The other half were made Sergeant Pilots, though how this rather arbitrary class-conscious division was made I never knew. We were also divided up into fighter pilots or bomber pilots, fliers either of single-engined planes or twins. I became a Pilot Officer and a fighter pilot. Then all sixteen of us said goodbye to one another and were whisked off in many different directions.

I found myself at a large RAF station on the Suez Canal called Ismailia, where they told me that I had been posted to 80 Squadron who were flying Gladiators against the Italians in the Western Desert of Libya. The Gloster Gladiator was an out-of-date fighter biplane with a radial engine. Back in England at that time, all the fighter boys were flying Hurricanes and Spitfires, but they were not sending any of those little beauties out to us in the Middle East quite yet.