Which Way to the Wild West?

Read Which Way to the Wild West? Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

For Judy and Nick,

heroic leaders in the fight against

boring history books

heroic leaders in the fight against

boring history books

Table of Contents

Title Page

How the West Moved West

How the West Moved West

Might as Well Start Here

Step 1: Ask for New Orleans

Step 2: Send in Monroe

Step 3: Buy Louisiana

Step 4: Hire Lewis and Clark

Step 5: Meet Your Neighbors

Step 6: Ask Directions

Step 7: Bring Back the News

Step 8: Become a Mountain Man

Step 9: Learn from the Locals

Step 10: Stumble to Santa Fe

Step 11: Move to Texas

Step 12: Meet Me in San Antonio

Step 1: Ask for New Orleans

Step 2: Send in Monroe

Step 3: Buy Louisiana

Step 4: Hire Lewis and Clark

Step 5: Meet Your Neighbors

Step 6: Ask Directions

Step 7: Bring Back the News

Step 8: Become a Mountain Man

Step 9: Learn from the Locals

Step 10: Stumble to Santa Fe

Step 11: Move to Texas

Step 12: Meet Me in San Antonio

Out of the Way of the Big Engine

The Rise and Fall of the Pony Express

Here Comes Crazy Judah

The Race for Milesâand Money

How to Steal Millions: Part I

How to Steal Millions: Part II

How to Steal Millions: Part III

Who's Going to Build This Thing?

An Old Problem Gets Worse

Sand Creek and Beyond

War Spreads North

The Shocking Fetterman Fight

And Now Comes the Railroad

This Time for Real

Here Comes Crazy Judah

The Race for Milesâand Money

How to Steal Millions: Part I

How to Steal Millions: Part II

How to Steal Millions: Part III

Who's Going to Build This Thing?

An Old Problem Gets Worse

Sand Creek and Beyond

War Spreads North

The Shocking Fetterman Fight

And Now Comes the Railroad

This Time for Real

Have you ever tried to negotiate a treaty for your country? Maybe not. Well, if you ever do, play it cool. You knowâdon't act too eager to make a deal.

This would have been good advice for Robert Livingston, the American ambassador to France. On the afternoon of April 11, 1803, Livingston was sitting in the office of the French foreign minister. The two men were chatting politely, until the Frenchman cut in with an offer that nearly knocked Livingston out of his chair.

A

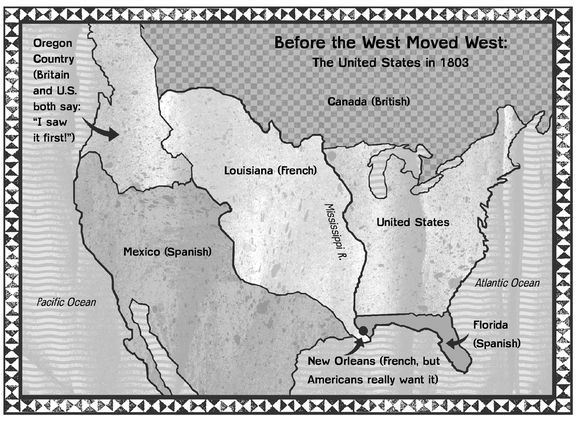

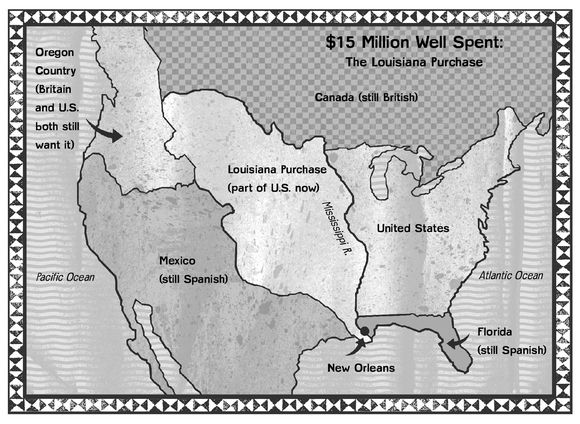

s Robert Livingston sat in Paris that day in 1803, the United States looked like this:

s Robert Livingston sat in Paris that day in 1803, the United States looked like this:

This is a good place to start a book about the American West. Because, as you can see, the land we call the West wasn't actually part of the United States yet. When Americans said “the West” back then, they meant Kentucky and Tennessee.

That was about to change. In fact, Livingston's trip to France

set off a series of events that quickly changed the size and shape of the United Statesâand the location of what we think of as the West. Here's how it happened.

set off a series of events that quickly changed the size and shape of the United Statesâand the location of what we think of as the West. Here's how it happened.

O

n the map you can see that the city of New Orleans was located in the French territory of Louisiana, near the mouth of the Mississippi River. When American farmers shipped their goods down the Mississippi, their ships had to pass through New Orleans before reaching the sea. This made Americans nervous. What if France suddenly shut this port to American shipping? The French could do it at any momentâthey had a much more powerful military than did the young United States.

n the map you can see that the city of New Orleans was located in the French territory of Louisiana, near the mouth of the Mississippi River. When American farmers shipped their goods down the Mississippi, their ships had to pass through New Orleans before reaching the sea. This made Americans nervous. What if France suddenly shut this port to American shipping? The French could do it at any momentâthey had a much more powerful military than did the young United States.

Terrified of losing their route to the sea, American farmers demanded action from Congress. Terrified of losing their jobs, members of Congress demanded action from President Thomas Jefferson. “Every eye in the United States is now fixed on this affair of Louisiana,” Jefferson moaned. “Perhaps nothing since the Revolutionary War has produced more uneasy sensations through the body of the nation.”

So Jefferson gave the ambassador Robert Livingston a new assignment: convince the French to sell New Orleans to the United States. That explains what Livingston was doing in the office of Charles de Talleyrand, the foreign minister of France, on April 11, 1803.

Talleyrand listened to Livingston's request. Then he suddenly said: “Would you Americans wish to have the whole of Louisiana?”

This was the point at which Livingston was in danger of collapsing.

By “the whole of Louisiana,” Talleyrand meant France's massive empire in North America, stretching from the Mississippi River all the way to the Rocky Mountains.

Hmm,

Livingston thought,

might be nice to add all that land to the United States.

But Jefferson's orders were

buy New Orleans,

not

buy half a continent.

Hmm,

Livingston thought,

might be nice to add all that land to the United States.

But Jefferson's orders were

buy New Orleans,

not

buy half a continent.

“No,” Livingston finally managed to say. “Our wishes extend only to New Orleans.”

But Talleyrand would not drop the subject. “I should like to know what you would give for the whole,” he insisted.

Sensing he was being offered the deal of a lifetime, Livingston pulled a number out of the air: twenty million francs (about four million dollars).

Charles de Talleyrand

Talleyrand waved the figure away as if swatting a fly. Much too low, he said. He told Livingston to think it over and get back to him with a serious offer.

B

ack in Washington, D.C., Jefferson was getting more and more worried about New Orleans. He had sent Livingston to buy the

place but hadn't heard any news yet. What was Livingston up to in Paris? What was taking so long?

ack in Washington, D.C., Jefferson was getting more and more worried about New Orleans. He had sent Livingston to buy the

place but hadn't heard any news yet. What was Livingston up to in Paris? What was taking so long?

Robert Livingston

Jefferson decided to send his trusted friend, James Monroe, to France to help speed up negotiations. When Monroe arrived, Livingston told him that the French had just offered to sell the United States all of Louisiana.

“All France's lands west of the Mississippi!” Livingston said to Monroe. “My, my! Why, no one even knows how much land that is. How many square miles, have we any idea?”

Monroe said he wasn't quite sure.

Anyway, he pointed out, they had no authority to buy all that land. And there was no way to check quickly with Jefferson, since getting letters back and forth across the ocean could take months. By then, the French might have changed their mind and taken back their offer.

Livingston and Monroe talked over what to do next.

W

hat the Americans didn't know: Napoleon was desperate for cash. As the emperor of France, Napoleon had the expensive hobby of invading neighboring nations. He needed money for his wars. That's why he wanted to sell Louisiana.

hat the Americans didn't know: Napoleon was desperate for cash. As the emperor of France, Napoleon had the expensive hobby of invading neighboring nations. He needed money for his wars. That's why he wanted to sell Louisiana.

Napoleon told his treasury minister, Francois de Barbé-Marbois, to get the deal done already. He insisted on getting one hundred million francs for Louisiana.

Barbé-Marbois pointed out that this was more cash than the United States government had.

“Make it fifty million then, but nothing less,” Napoleon said. “I must get real money for the war with England.”

Now it was Barbé-Marbois's turn to play it coolâor, to try to. He waited a couple of days, expecting Livingston and Monroe to come to his office. When the Americans didn't show up, he started to sweat.

Emperor Napoleon

Livingston and Monroe were still trying to figure out what to do. They invited some friends for dinner and were talking things over when they noticed someone watching them from the garden behind the house.

“Doesn't that look like Barbé-Marbois out there?” asked one of the dinner guests.

“It is! It is!” cried Livingston.

Yes, the treasury minister of France was peeking through their dining room window. So much for playing it cool.

Livingston went to the window and invited Barbé-Marbois to come around to the door. Then the two men had a short, awkward conversation.

Livingston and Monroe realized the French were eager to make a deal. And they took a chance, guessing Jefferson would want Louisiana (he did). Over the next couple of weeks, the American and French negotiators hammered out the details of what became the Louisiana Purchase. The United States paid fifteen million dollars (75 million francs) for the Louisiana Territoryâless than four cents an acre.

The purchase instantly doubled the size of the United States, which now looked like this:

O

f course, it's easy to draw maps these days. But back in 1803 the Americans didn't really know what they had just bought, or who lived there. Thomas Jefferson gave the job of finding out to two explorers: Meriwether Lewis and William Clark.

f course, it's easy to draw maps these days. But back in 1803 the Americans didn't really know what they had just bought, or who lived there. Thomas Jefferson gave the job of finding out to two explorers: Meriwether Lewis and William Clark.

Lewis and Clark's mission was to explore the land, study new plants and animals, find rivers leading from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean (there aren't any), and establish friendly relations with Native American tribes. The two explorers put together a thirty-three-man team they called the Corps of Discovery, made up mostly of young soldiers. The crew included one African American, a young man named York. (Clark called him “my manservant.” Actually, York was Clark's slave.)

The Corps of Discovery set out from St. Louis, Missouri, in May 1804.

Other books

The Mating Call: Drekinn Series by Jana Leigh

These Few Precious Days by Christopher Andersen

Madison Johns - Agnes Barton Paranormal 02 - Ghostly Hijinks by Madison Johns

The Hundred-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out of the Window and Disappeared by Jonas Jonasson

To Catch a Highlander: A Highland Erotic Romance by LaCroix, Krystal

Dangerous Depths by Colleen Coble

Finding Home (Montana Born Homecoming Book 2) by Snopek, Roxanne

Promiscuous by Isobel Irons

Onyx by Elizabeth Rose