Going Interstellar (11 page)

Read Going Interstellar Online

Authors: Les Johnson,Jack McDevitt

The levitated ice ball concept might be workable in the frigid wastes of interstellar space. But frozen anti-hydrogen might be very hard to store in the much hotter environment of a near-Sun antimatter factory.

We are a long way away from being able to produce and store the amounts of antimatter needed for an interstellar voyage.

Antimatter Rockets

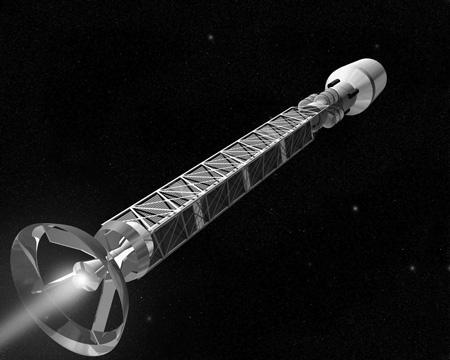

Antimatter technology is in its infancy. But as it matures, its application to space flight is a natural outcome. Figure 1 presents major features of an antimatter rocket. The payload rides ahead of the fuel tanks. The fuel consists of normal matter (probably hydrogen) and antimatter. Antimatter is fed into an “annihilation chamber” where it reacts with normal matter. An electromagnetic nozzle is used to expel the charged particles as exhaust.

Figure 1. Artist concept of an antimatter rocket. (Image courtesy of NASA.)

Let’s say we desire an interstellar cruise velocity of 0.09c after all the fuel is expelled, which allows a ship to reach Alpha Centauri in about fifty years (not counting the time required for acceleration and deceleration).

If our starship has a mass of about one million kilograms, then it would require twelve thousand eight hundred kilograms of antimatter. The hypothetical Mercury-based antimatter factory discussed in a previous section could produce this mass of antiprotons in about twenty-five years.

Instead of a crewed starship, let’s say we wish to launch a robotic probe with an unfueled mass of one thousand kilograms. In this case, only 12.8 kilograms of antimatter will be required! And if further miniaturization is possible, the antimatter mass required for an interstellar probe can be reduced still further.

We next consider the acceleration process. If the ship requires about 10 years to accelerate an average of about 10

7

kilograms of matter will be converted into energy each second. The probe generates matter/antimatter annihilation energy at an approximate average rate of 10

10

watts, roughly equivalent to that of a large city. The ship’s generated power level will be about one thousand times greater, approximating that of our entire global civilization! Antimatter propulsion is clearly not for the faint hearted!

***

Further Reading

Early antimatter history has been discussed in many archival sources. One such is H. A. Boorse and L. Motz, ed.,

The World of the Atom

, Basic Books, NY (1966).

The story of the antiproton is eloquently told by L. Yarris in “The Golden Anniversary of the Antiproton,” Science @ Berkeley Lab (Oct. 27, 2005), http://newscenter.lbl.gov/feature-stories/2005/10/27/

the-golden-anniversary-of-the-antiproton/

For further information regarding possible biomedical antiproton applications, check out L. Gray and T. E. Kalogeropoulos, “Possible Biomedical Applications of Antiproton Beams: Focused Radiation Transfer,”

Radiation Research

, 97, 246-252 (1984).

Many sources have speculated on possible military applications of antiprotons. Two web references on this topic, both by Andre Gsponer and John-Pierre Hurni, “Antimatter Underestimated,” arXiv:physics/0507139v1 [physics.soc-ph] 19 Jul 2005 and “Antimatter Weapons,” http://cul.unige.ch.isi/sscr/phys/antim-BPP.html

Many astronomy texts consider the early moments of the universe when matter (and antimatter) formed. One readable text, authored by Eric Chaisson and Steve McMillan, is

Astronomy Today

, 3

rd

ed., Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ (1999).

Sanger’s photon rocket is described by Eugene Mallove and Gregory Matloff in

The Starflight Handbook

, Wiley, NY (1989). This book also discusses the decay scheme for the proton-antiproton annihilation reaction.

Robert Forward’s work is reviewed in

The Starflight Handbook

and other interstellar monographs. His final report to the US Air Force Rocket Propulsion Laboratory is entitled AFRPL TR-83-067, “Alternate Propulsion Energy Sources.” Many of Bob Forward’s ideas regarding antimatter (and a host of other subjects) are also published in a more accessible form: R. Forward,

Indistinguishable from Magic

, Baen, Riverdale, NY (1995).

Antimatter production by black holes is described by C. Bambi, A. D. Dogov and A. A. Petrov in “Black Holes as Antimatter Factories,” which was published in Sept. 2009 in the

Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics

, which is an on-line journal. This paper is also available from a physics archive as arXiv.org/astro-ph>arXiv:086.3440v2.

A NASA web publication, titled “Antimatter Factory on Sun Yields Clues to Solar Explosions,” describes the discovery of gamma rays in solar flares. http://www.nasa.gov/vision/universe/solarsystem/rhessi

_antimatter.html.

To learn more about the surprising discovery of positrons associated with terrestrial lightning discharges, consult R. Cowen, “Signature of Antimatter Detected in Lightning,” www.wired.com/wiredscience/2009//11/antimatter-lightning/.

Information regarding the current capabilities of the Tevatron was obtained from Wikipedia and the Fermilab website. Operational details regarding the Large Hadron Collider are available on the CERN website.

Many books on SETI (the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) deal with the Kardashev scheme for categorizing the capabilities of advanced technological civilizations. A very readable and authoritative one is W. Sullivan’s

We Are Not Alone

, revised edition, Dutton, NY (1993).

A number of researchers have considered the application of solar-sail technology to the construction of huge planetary sunshades or solar collectors. Analysis by Robert Kennedy, Ken Roy and David Fields is discussed and reviewed by L. Johnson, G. L. Matloff and C Bangs in

Paradise Regained: The Regreening of Earth

, Springer-Copernicus, NY (2009).

The cited antimatter-storage paper by S. D. Howe and G. A. Smith is entitled “Development of High-Capacity Antimatter Storage.” It was delivered at the Space-Technology and Applications International Forum-2000, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, July 30-February 3, 2000 and is available on line.

LUCY

Jack McDevitt

Jack McDevitt is a former English teacher (the first of three in this anthology), naval officer, Philadelphia taxi driver, customs officer and a motivational trainer. He is a Nebula Award-winning author and John W. Campbell Memorial Award winner. Jack also served as one of the editors of this anthology.

In

“Lucy,”

Jack merges two favorite themes of futurists—artificial intelligence and deep space travel—into a story that actually makes you care deeply about the fate of a sentient computer.

***

“We’ve lost the

Coraggio

.”

Calkin’s voice was frantic. “The damned thing’s gone, Morris.”

When the call came in, I’d been assisting at a simulated program for a lunar reclamation group, answering phones for eleven executives, preparing press releases on the Claymont and Demetrius projects, opening doors and turning on lights for a local high-school tour group, maintaining a cool air flow on what had turned into a surprisingly warm March afternoon, and playing chess with Herman Mills over in Archives. It had been, in other words, a routine day. Until the Director got on the line.

Denny Calkin is a small, narrow man, in every sense of the word. And he has a big voice. He was a political appointment at NASA, and consequently was in over his head. He thought well of himself, of course, and believed he had the answers to everything. On this occasion, though, he verged on hysteria. “Morris, did you hear what I said?” He didn’t wait for an answer. “We’ve lost the

Coraggio

.”

“How’s that again, Denny? What do you mean,

lost

the

Coraggio

?”

“What do you think I mean? Lucy isn’t talking to us anymore. We haven’t a clue where she is or what’s going on out there.”

Morris’s face went absolutely white. “That’s not possible. What are you telling me, Denny?”

“The Eagle Project just went over the cliff, damn it.”

“You have any idea what might be wrong?”

“No. She’s completely shut down, Morris.” He said it as if he were talking to a six-year-old.

“Okay.” Morris tried to assume a calm demeanor. “How long ago?”

“It’s been about five hours. She missed her report and we’ve been trying to raise her since.”

“All right.”

“We’re trying to keep it quiet. But we won’t be able to do that much longer.”

The

Coraggio

, with its fusion drive and array of breakthrough technology, had arrived in the Kuiper Belt two days earlier and at 3:17 a.m. Eastern Time had reported sighting its objective, the plutoid Minetka. It had been the conclusion of a 4.7 billion-mile flight.

Morris was always unfailingly optimistic. It was a quality he needed during these days of increasingly tight budgets. “It’s probably just a transmission problem, Denny.”

“I hope so! But I doubt it.”

“So what are we doing?”

“Right now, we’re stalling for time. And hoping Lucy comes back up.”

“And if she doesn’t?”

“That’s why I’m calling you. Look, we don’t want to be the people who lost a twenty-billion-dollar vehicle. If she doesn’t respond, we’re going to have to go out after her.”

“Is the

Excelsior

ready?”

“We’re working on it.”

“So what do you need from me, Denny?”

He hesitated. “Baker just resigned.”

“Oh. Already?”

“Well, he’s

going

to be resigning.”

Over in the museum, one of the high school students asked a question about the Apollo flights, what it felt like to be in a place where there was no gravity. The teacher directed it to me, and I answered as best I could, saying that it was a little like being in water, that you just sort of floated around, but that you got used to it very quickly. Meantime I made a rook move against Herman, pinning a knight. Then Morris said what he was thinking. “I’m sorry to hear it.” It was an accusation.

“Sometimes we have to make sacrifices, Morris. Maybe we’ll get a break and they’ll come back up.”

“But nobody expects it to happen.”

“No.” There was a sucking sound: Calkin chewing on his lower lip.

“It leaves us without an operations chief.”

“That’s why—”

“—You need me.”

“Yes, Morris, that’s why we need you. I want you to come to the Cape posthaste and take over.”

“Do you have any idea at all what the problem might be?”

“Nothing.”

“So you’re just going to send the

Excelsior

out and hope for the best.”

“What do you suggest?”

“In all probability, you’ve had a breakdown in the comm system. Or it’s the AI.”

“That’s my guess.”

“You’ve checked the comm system in the

Excelsior

?”

“Not yet. They’re looking at it now.”

“Good. What about the AI?”

“We’re going to run some tests on Jeri, too. Don’t worry about it, Morris, okay? You just get down here and launch this thing.”

“Denny, Jeri and Lucy are both Bantam level-3 systems.”

“So what are you saying, Morris? Those are the best SIs we have. You know that.”

“I also know they’re untested.”

“That’s not true. We ran multiple simulations—”

“That’s not the same as onboard operations.”

“Morris, there’s no point doing all those tests again. We’d get the same results. There’s nothing wrong with the Bantams.”

“Okay, Denny. But we’ve got a battle-tested system already. We know it works. Why not use it?”

“Because we’ve spent too much money on the Bantams, damn it.”

“Denny, Sara’s done all the test flights with the

Coraggio

. If we use her, it removes one potential source of trouble from the equation.”

I liked the sound of that. I’d have smiled if I could, while I finished a press release for an upcoming welcome-back event for several cosmonauts and astronauts. I felt sorry for them. They’d been on active duty for an average of nineteen years, and none of them had ever gotten beyond the space station. Calkin responded just as I was sending the document to the public information office. “We’ll talk about it when you get here.”

He hung up, and it was a long minute before Morris put the phone down. He’d been an astronaut himself, more years ago than he wanted to remember. Now he sat staring out the window. And finally he took a deep breath: “Sara?”

“I heard, Morris.”

“What do you think?”

“The most vulnerable piece of equipment on the ship is the AI.”

“You wouldn’t really mind that, would you? If the Bantams are screwed up some way.”