Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (17 page)

Read Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid Online

Authors: Douglas R. Hofstadter

Tags: #Computers, #Art, #Classical, #Symmetry, #Bach; Johann Sebastian, #Individual Artists, #Science, #Science & Technology, #Philosophy, #General, #Metamathematics, #Intelligence (AI) & Semantics, #G'odel; Kurt, #Music, #Logic, #Biography & Autobiography, #Mathematics, #Genres & Styles, #Artificial Intelligence, #Escher; M. C

Tortoise: Curious that you should think so ... I don't suppose that you know Godel's Incompleteness Theorem backwards and forwards, do you?

Achilles: Know WHOSE Theorem backwards and forwards? I've

heard of anything that sounds like that. I'm sure it's fascinating, but I'd rather hear more about "music to break records by". It's an amusing little story. Actually, I guess I can fill in the end. Obviously, there was no point in going on, and so you sheepishly admitted defeat, and that was that. Isn't that exactly it?

Tortoise: What! It's almost midnight! I'm afraid it's my bedtime. I'd love to talk some more, but really I am growing quite sleepy.

Achilles: As am 1. Well, 1 u be on my way. (

As he reaches the door, he suddenly stops,

and turns around

.) Oh, how silly of me! I almost forgo brought you a little present. Here. (Hands

the Tortoise a small neatly wrapped package

.) Tortoise: Really, you shouldn't have! Why, thank you very much indeed think I'll open it now. (

Eagerly tears open the package, and ins discovers a glass goblet

.) Oh, what an exquisite goblet! Did y know that I am quite an aficionado for, of all things, gl goblets?

Achilles: Didn't have the foggiest. What an agreeable coincidence!

Tortoise: Say, if you can keep a secret, I'll let you in on something: I trying to find a Perfect goblet: one having no defects of a sort in its shape. Wouldn't it be something if this goblet-h call it "G"-were the one? Tell me, where did you come across Goblet G?

Achilles: Sorry, but that's MY little secret. But you might like to know w its maker is.

Tortoise: Pray tell, who is it?

Achilles: Ever hear of the famous glassblower Johann Sebastian Bach? Well, he wasn't exactly famous for glassblowing-but he dabbled at the art as a hobby, though hardly a soul knows it-a: this goblet is the last piece he blew.

Tortoise: Literally his last one? My gracious. If it truly was made by Bach its value is inestimable. But how are you sure of its maker

Achilles: Look at the inscription on the inside-do you see where tletters `B', À', `C', `H'

have been etched?

Tortoise: Sure enough! What an extraordinary thing. (Ge

ntly sets Goblet G down on a

shelf.

) By the way, did you know that each of the four letters in\Bach's name is the name of a musical note?

Achilles:' tisn't possible, is it? After all, musical notes only go from ‘A’ through `G'.

Tortoise: Just so; in most countries, that's the case. But in Germany, Bach’s own homeland, the convention has always been similar, except that what we call `B', they call `H', and what we call `B-flat', they call `B'. For instance, we talk about Bach's "Mass in B Minor whereas they talk about his "H-moll Messe". Is that clear?

Achilles:

... hmm ... I guess so. It's a little confusing: H is B, and B B-flat. I suppose his name actually constitutes a melody, then

Tortoise: Strange but true. In fact, he worked that melody subtly into or of his most elaborate musical pieces-namely, the final

Contrapunctus

in his

Art of the Fugue

.

It was the last fugue Bach ever wrote. When I heard it for the first time, I had no idea how would end. Suddenly, without warning, it broke off. And the ... dead silence. I realized immediately that was where Bach died. It is an indescribably sad moment, and the effect it had o me was-shattering. In any case, B-A-C-H is the last theme c that fugue. It is hidden inside the piece. Bach didn't point it out

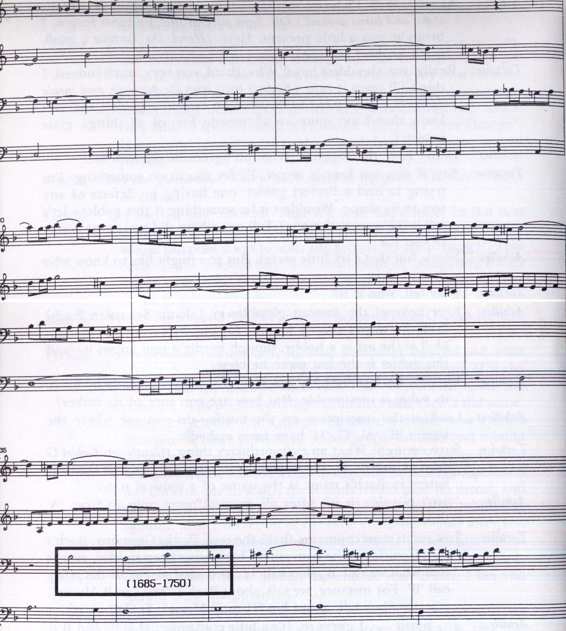

FIGURE 19. The last page of Bach's Art of the Fugue. In the original manuscript, in the

handwriting of Bach's son Carl Philipp Emanuel, is written: "N.B. In the course of this

fugue, at the point where the name B.A.C.H. was brought in as countersubject, the

composer died." (B-A-C-H in box.) I have let this final page of Bach's last fugue serve as

an epitaph.

[Music Printed by Donald Byrd's program "SMUT", developed at Indiana University]

Explicitly, but if you know about it, you can find it without much trouble. Ah, me-there are so many clever ways of hiding things in music .. .

Achilles: . . or in poems. Poets used to do very similar things, you know (though it's rather out of style these days). For instance, Lewis Carroll often hid words and names in the first letters (or characters) of the successive lines in poems he wrote.

Poems which conceal messages that way are called "acrostics".

Tortoise: Bach, too, occasionally wrote acrostics, which isn't surprising. After all, counterpoint and acrostics, with their levels of hidden meaning, have quite a bit in common. Most acrostics, however, have only one hidden level-but there is no reason that one couldn't make a double-decker-an acrostic on top of an acrostic.

Or one could make a "contracrostic"-where the initial letters, taken in reverse order, form a message. Heavens! There's no end to the possibilities inherent in the form. Moreover, it's not limited to poets; anyone could write acrostics-even a dialogician.

Achilles: A dial-a-logician? That's a new one on me.

Tortoise: Correction: I said "dialogician", by which I meant a writer of dialogues. Hmm

... something just occurred to me. In the unlikely event that a dialogician should write a contrapuntal acrostic in homage to J. S. Bach, do you suppose it would be more proper for him to acrostically embed his OWN name-or that of Bach? Oh, well, why worry about such frivolous matters? Anybody who wanted to write such a piece could make up his own mind. Now getting back to Bach's melodic name, did you know that the melody B-A-C-H, if played upside down and backwards, is exactly the same as the original?

Achilles: How can anything be played upside down? Backwards, I can see-you get H-C-A-B-but upside down? You must be pulling my leg.

Tortoise: ' pon my word, you're quite a skeptic, aren't you? Well, I guess I'll have to give you a demonstration. Let me just go and fetch my fiddle- (Walks into the next room, and returns in a jiffy with an ancient-looking violin.) -and play it for you forwards and backwards and every which way. Let's see, now ... (Places his copy of the Art of the Fugue on his music stand and opens it to the last page.) ... here's the last Contrapunctus, and here's the last theme ...

The Tortoise begins to play: B-A-C- - but as he bows the final H, suddenly,

without warning, a shattering sound rudely interrupts his performance. Both

he and Achilles spin around, just in time to catch a glimpse of myriad

fragments of glass tinkling to the floor from the shelf where Goblet G had

stood, only moments before. And then ... dead silence.

Consistency, Completeness,

and Geometry

Implicit and Explicit Meaning

IN CHAPTER II, we saw how meaning-at least in the relatively simple context of formal systems-arises when there is an isomorphism between rule-governed symbols, and things in the real world. The more complex the isomorphism, in general, the more "equipment"-

both hardware and software-is required to extract the meaning from the symbols. If an isomorphism is very simple (or very familiar), we are tempted to say that the meaning which it allows us to see is explicit. We see the meaning without seeing the isomorphism.

The most blatant example is human language, where people often attribute meaning to words in themselves, without being in the slightest aware of the very complex

"isomorphism" that imbues them with meanings. This is an easy enough error to make. It attributes all the meaning to the object (the word), rather than to the link between that object and the real world. You might compare it to the naive belief that noise is a necessary side effect of any collision of two objects. This is a false belief; if two objects collide in a vacuum, there will be no noise at all. Here again, the error stems from attributing the noise exclusively to the collision, and not recognizing the role of the medium, which carries it from the objects to the ear.

Above, I used the word "isomorphism" in quotes to indicate that it must be taken with a grain of salt. The symbolic processes which underlie the understanding of human language are so much more complex than the symbolic processes in typical formal systems, that, if we want to continue thinking of meaning as mediated by isomorphisms, we shall have to adopt a far more flexible conception of what isomorphisms can be than we have up till now. In my opinion, in fact, the key element in answering the question

"What is consciousness?" will be the unraveling of the nature of the "isomorphism"

which underlies meaning.

Explicit Meaning of the

Contracrostipunctus

All this is by way of preparation for a discussion of the

Contracrostipunctus

-a study in levels of meaning. The Dialogue has both explicit and implicit meanings. Its most explicit meaning is simply the story

Which was related. This “explicit meaning is, strictly speaking extremely

implicit

, in the sense that the brain processes required to understand the events in the story, given only the black marks on paper, are incredibly complex. Nevertheless, we shall consider the events in the story to be the explicit meaning of the Dialogue, and assume that every reader of English uses more or less the same "isomorphism" in sucking that meaning from the marks on the paper.

Even so, I'd like to be a little more explicit about the explicit meaning of the story.

First I'll talk about the record players and the records. The main point is that there are two levels of meaning for the grooves in the records. Level One is that of music. Now what is

"music"-a sequence of vibrations in the air, or a succession of emotional responses in a brain? It is both. But before there can be emotional responses, there have to be vibrations.

Now the vibrations get "pulled" out of the grooves by a record player, a relatively straightforward device; in fact you can do it with a pin, just pulling it down the grooves.

After this stage, the ear converts the vibrations into firings of auditory neurons in the brain. Then ensue a number of stages in the brain, which gradually transform the linear sequence of vibrations into a complex pattern of interacting emotional responses-far too complex for us to go into here, much though I would like to. Let us therefore content ourselves with thinking of the sounds in the air as the "Level One" meaning of the grooves.

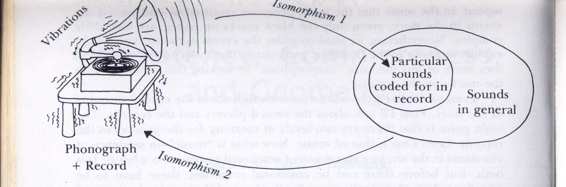

What is the Level Two meaning of the grooves? It is the sequence of vibrations induced in the record player. This meaning can only arise after the Level One meaning has been pulled out of the grooves, since the vibrations in the air cause the vibrations in the phonograph. Therefore, the Level Two meaning depends upon a chain of two isomorphisms:

(1) Isomorphism between arbitrary groove patterns and air

vibrations;

(2) Isomorphism between graph vibrations. arbitrary air

vibrations and phonograph vibrations

This chain of two isomorphisms is depicted in Figure 20. Notice that isomorphism I is the one which gives rise to the Level One meaning. The Level Two meaning is more implicit than the Level One meaning, because it is mediated by the chain of two isomorphisms. It is the Level Two meaning which "backfires", causing the record player to break apart.

What is of interest is that the production of the Level One meaning forces the production of the Level Two meaning simultaneously-there is no way to have Level One without Level Two. So it was the implicit meaning of the record which turned back on it, and destroyed it.

Similar comments apply to the goblet. One difference is that the mapping from letters of the alphabet to musical notes is one more level of isomorphism, which we could call "transcription". That is followed by "translation"-conversion of musical notes into musical sounds. Thereafter, the vibrations act back on the goblet just as they did on the escalating series of phonographs.