Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (128 page)

Read Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid Online

Authors: Douglas R. Hofstadter

Tags: #Computers, #Art, #Classical, #Symmetry, #Bach; Johann Sebastian, #Individual Artists, #Science, #Science & Technology, #Philosophy, #General, #Metamathematics, #Intelligence (AI) & Semantics, #G'odel; Kurt, #Music, #Logic, #Biography & Autobiography, #Mathematics, #Genres & Styles, #Artificial Intelligence, #Escher; M. C

undermines itself in a Gödelian way, and I am incomplete for that reason. Cases (1) and (2) are predicated on my being 100 per cent consistent-a very unlikely state of affairs.

More likely is that I am inconsistent-but that's worse, for then inside me there are contradictions, and how can I ever understand that?

Consistent or inconsistent, no one is exempt from the mystery of the self.

Probably we are all inconsistent. The world is just too complicated for a person to be able to afford the luxury of reconciling all of his beliefs with each other. Tension and confusion are important in a world where many decisions must be made quickly, Miguel de Unamuno once said, "If a person never contradicts himself, it must be that he says nothing." I would say that we all are in the same boat as the Zen master who, after contradicting himself several times in a row, said to the confused Doko, "I cannot understand myself."

Gödel’s Theorem and Personal Nonexistence

Perhaps the greatest contradiction in our lives, the hardest to handle, is the knowledge

"There was a time when I was not alive, and there will come a time when I am not alive."

On one level, when you "step out of yourself" and see yourself as "just another human being", it makes complete sense. But on another level, perhaps a deeper level, personal nonexistence makes no sense at all. All that we know is embedded inside our minds, and for all that to be absent from the universe is not comprehensible. This is a basic undeniable problem of life; perhaps it is the best metaphorical analogue of Gödel’s Theorem. When you try to imagine your own nonexistence, you have to try to jump out of yourself, by mapping yourself onto someone else. You fool yourself into believing that you can import an outsider's view of yourself into you, much as

TNT

"believes" it mirrors its own metatheory inside itself. But

TNT

only contains its own metatheory up to a certain extent-not fully. And as for you, though you may imagine that you have jumped out of yourself, you never can actually do so-no more than Escher's dragon can jump out of its native two-dimensional plane into three dimensions. In any case, this contradiction is so great that most of our lives we just sweep the whole mess under the rug, because trying to deal with it just leads nowhere.

Zen minds, on the other hand, revel in this irreconcilability. Over and over again, they face the conflict between the Eastern belief: "The world and I are one, so the notion of my ceasing to exist is a contradiction in terms" (my verbalization is undoubtedly too Westernized-apologies to Zenists), and the Western belief: "I am just part of the world, and I will die, but the world will go on without me."

Science and Dualism

Science is often criticized as being too "Western" or "dualistic"-that is, being permeated by the dichotomy between subject and object, or observer

and observed. While it is true that up until this century, science was exclusively concerned with things which can be readily distinguished from their human observers-such as oxygen and carbon, light and heat, stars and planets, accelerations and orbits, and so on-this phase of science was a necessary prelude to the more modern phase, in which life itself has come under investigation. Step by step, inexorably, "Western" science has moved towards investigation of the human mind-which is to say, of the observer.

Artificial Intelligence research is the furthest step so far along that route. Before AI came along, there were two major previews of the strange consequences of the mixing of subject and object in science. One was the revolution of quantum mechanics, with its epistemological problems involving the interference of the observer with the observed.

The other was the mixing of subject and object in metamathematics, beginning with Godel's Theorem and moving through all the other limitative'Theorems we have discussed. Perhaps the next step after Al will be the self-application of science: science studying itself as an object. This is a different manner of mixing subject and object-perhaps an even more tangled one than that of humans studying their own minds.

By the way, in passing, it is interesting to note that all results essentially dependent on the fusion of subject and object have been limitative results. In addition to the limitative Theorems, there is Heisenberg's uncertainty principle, which says that measuring one quantity renders impossible the simultaneous measurement of a related quantity. I don't know why all these results are limitative. Make of it what you will.

Symbol vs. Object in Modern Music and Art

Closely linked with the subject-object dichotomy is the symbol-object dichotomy, which was explored in depth by Ludwig Wittgenstein in the early part of this century. Later the words "use" and "mention" were adopted to make the same distinction. Quine and others have written at length about the connection between signs and what they stand for. But not only philosophers have devoted much thought to this deep and abstract matter. In our century both music and art have gone through crises which reflect a profound concern with this problem. Whereas music and painting, for instance, have traditionally expressed ideas or emotions through a vocabulary of "symbols" (i.e. visual images, chords, rhythms, or whatever), now there is a tendency to explore the capacity of music and art to not express anything just to be. This means to exist as pure globs of paint, or pure sounds, but in either case drained of all symbolic value.

In music, in particular, John Cage has been very influential in bringing a Zen-like approach to sound. Many of his pieces convey a disdain for "use" of sounds-that is, using sounds to convey emotional states-and an exultation in "mentioning" sounds-that is, concocting arbitrary juxtapositions of sounds without regard to any previously formulated code by which a listener could decode them into a message. A typical example is

"Imaginary Landscape no. 4", the polyradio piece described in Chapter VI. I may not

be doing Cage justice, but to me it seems that much of his work has been directed at bringing meaninglessness into music, and in some sense, at making that meaninglessness have meaning. Aleatoric music is a typical exploration in that direction. (Incidentally, chance music is a close cousin to the much later notion of "happenings" or "be-in"' s.) There are many other contemporary composers who are following Cage's lead, but few with as much originality. A piece by Anna Lockwood, called "Piano Burning", involves just that-with the strings stretched to maximum tightness, to make them snap as loudly as possible; in a piece by LaMonte Young, the noises are provided by shoving the piano all around the stage and through obstacles, like a battering ram.

Art in this century has gone through many convulsions of this general type. At first there was the abandonment of representation, which was genuinely revolutionary: the beginnings of abstract art. A gradual swoop from pure representation to the most highly abstract patterns is revealed in the work of Piet Mondrian. After the world was used to nonrepresentational art, then surrealism came along. It was a bizarre about-face, something like neoclassicism in music, in which extremely representational art was

"subverted" and used for altogether new reasons: to shock, confuse, and amaze. This school was founded by Andre Breton, and was located primarily in France; some of its more influential members were Dali, Magritte, de Chirico, Tanguy.

Magritte's Semantic Illusions

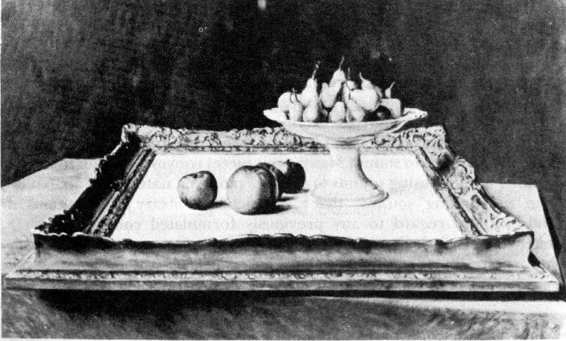

Of all these artists, Magritte was the most conscious of the symbol-object mystery (which I see as a deep extension of the use-mention distinction). He uses it to evoke powerful responses in viewers, even if the viewers do not verbalize the distinction this way. For example, consider his very strange variation on the theme of still life, called

Common

Sense

(Fig. 137).

FIGURE 137.

Common Sense, by Rene Magritte (1945-46).

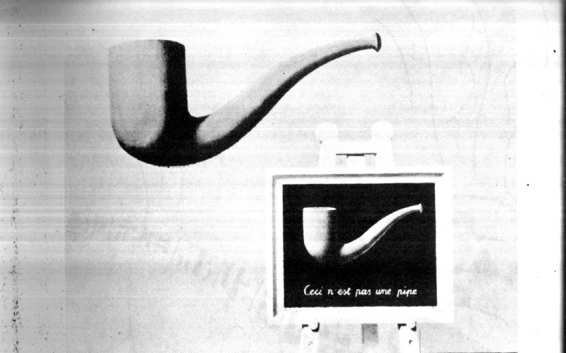

FIGURE 138.

The Two Mysteries, by Rene Magritte (1966)

.

Here, a dish filled with fruit, ordinarily the kind of thing represented inside a still life, is shown sitting on top of a blank canvas. The conflict between the symbol and the real is great. But that is not the full irony, for of course the whole thing is itself just a painting-in fact, a still life with nonstandard subject matter.

Magritte's series of pipe paintings is fascinating and perplexing. Consider

The

Two Mysteries

(Fig. 138). Focusing on the inner painting, you get the message that symbols and pipes are different. Then your glance moves upward to the "real" pipe floating in the air-you perceive that it is real, while the other one is just a symbol. But that is of course totally wrong: both of them are on the same flat surface before your eyes.

The idea that one pipe is in a twice-nested painting, and therefore somehow "less real"

than the other pipe, is a complete fallacy. Once you are willing to "enter the room", you have already been tricked: you've fallen for image as reality. To be consistent in your gullibility, you should happily go one level further down, and confuse image-within-image with reality. The only way not to be sucked in is to see both pipes merely as colored smudges on a surface a few inches in front of your nose. Then, and only then, do you appreciate the full meaning of the written message "Ceci West pas une pipe"-but ironically, at the very instant everything turns to smudges, the writing too turns to smudges, thereby losing its meaning! In other words, at that instant, the verbal message of the painting self-destructs in a most Gödelian way.

FIGURE 139.

Smoke Signal. [Drawing by the author.

]

The Air and the Song (Fig. 82), taken from a series by Magritte, accomplishes all that

The Two Mysteries

does, but in one level instead of two. My drawings Sm

oke Signal

and Pipe Dream

(Figs. 139 and 140) constitute "Variations on a Theme of Magritte". Try staring at

Smoke Signal

for a while. Before long, you should be able to make out a hidden message saying, "Ceci n'est pas un message". Thus, if you find the message, it denies itself-yet if you don't, you miss the point entirely. Because of their indirect self-snuffing, my two pipe pictures can be loosely mapped onto Gödel’s G-thus giving rise to a

"Central Pipemap", in the same spirit as the other "Central Xmaps": Dog, Crab, Sloth.

A classic example of use-mention confusion in paintings is the occurrence of a palette in a painting. Whereas the palette is an illusion created by the representational skill of the painter, the paints on the painted palette are literal daubs of paint from the artist's palette. The paint plays itself-it does not symbolize anything else. In

Don

Giovanni

, Mozart exploited a related trick: he wrote into the score explicitly the sound of an orchestra tuning up. Similarly, if I want the letter 'I' to play itself (and not symbolize me), I put 'I' directly into my text; then I enclose Ì' between quotes. What results is ' I"