Gimme Something Better (5 page)

Read Gimme Something Better Online

Authors: Jack Boulware

Danny Furious:

San Francisco Art Institute was a refuge for lost souls. We liberated one of the painting studios and set up house, complete with stove, fridge, sleeping bags and bags of speed. Hung a “Keep Out” sign on the door. The administration threw us out and turned Room 113 into a storage facility.

San Francisco Art Institute was a refuge for lost souls. We liberated one of the painting studios and set up house, complete with stove, fridge, sleeping bags and bags of speed. Hung a “Keep Out” sign on the door. The administration threw us out and turned Room 113 into a storage facility.

Penelope Houston:

We started in June of ’77. I had friends that had gone to art school with Danny Furious, and he dropped out or graduated or something.

We started in June of ’77. I had friends that had gone to art school with Danny Furious, and he dropped out or graduated or something.

Danny Furious:

Penelope came to school every day dressed to the nines, with full makeup and ’50s polka-dot dresses, petticoats, high heels and jewelry. She was stunning.

Penelope came to school every day dressed to the nines, with full makeup and ’50s polka-dot dresses, petticoats, high heels and jewelry. She was stunning.

Penelope Houston:

Danny said he was starting this band with his friend from Orange County, Greg, and they had stuff set up in a warehouse on Third Street.

Danny said he was starting this band with his friend from Orange County, Greg, and they had stuff set up in a warehouse on Third Street.

Danny Furious:

At that point we were just rehearsing old Stones and various other sundry garage.

At that point we were just rehearsing old Stones and various other sundry garage.

Penelope Houston:

I was hanging out at the warehouse, and nobody was there. The P.A. was set up, and I started messing around. When they came back from wherever they were, I was like, “I’m gonna be your singer.” And they were like, okay. So we did one show at the warehouse where we just did cover songs. And then we went to L.A. and the Screamers told me, “You gotta write your own material. You can’t do cover songs.”

I was hanging out at the warehouse, and nobody was there. The P.A. was set up, and I started messing around. When they came back from wherever they were, I was like, “I’m gonna be your singer.” And they were like, okay. So we did one show at the warehouse where we just did cover songs. And then we went to L.A. and the Screamers told me, “You gotta write your own material. You can’t do cover songs.”

We had a show one week later playing at the Mabuhay for this party the Nuns were throwing. Nobody had ever heard of us. We’d only been together for about two weeks. And in that one week, we wrote like six original songs. A couple of them lasted, “Car Crash” and “I Believe in Me.” “My Boyfriend’s a Pinhead.” One called “Vernon Is a Fag.” “Vernon Is a Fag” was graffiti all over San Francisco at that time.

We made it through one song, and the band started playing the second song, and I was like, “I don’t even know what song this is. This doesn’t even sound familiar to me.” They were playing two different songs. And then, after a few measures, they just stopped playing and everyone looked up and said, “What are you playing?” “I’m playing this.” “Well, I’m playing that.” And then we figured out that the set list had been wrong.

And we went from there. I was an art student, and I was living on my scholarship. Jimmy worked at a restaurant, and he’s the source of the song “White Nigger.” I don’t know if Greg had a job or not. I don’t think Danny had a job. He just bossed everybody around.

We all lived together, sharing apartments with other punk rockers. When I did a gig I would take the money and put it in one of my coat pockets in a closet. Like, here’s the rent money. Here’s some money for the bills, put ’em in another coat pocket. And then when the time of month came around to pay bills or rent, I would be going through all my pockets in the closet trying to find that money.

There was no scene outside of North Beach. The Haight was just dead—burnt-out, drugged-out hippies. South of Market there were a couple places to play, but nothing regular. Some people lived in warehouses out on Third Street.

We played the Mabuhay a lot. Like two nights every month. Once Dirksen realized we drew people.

Edwin Heaven:

The Nuns introduced the Avengers at a show in Rodeo, it was a biker club. Penelope was very Art Institute, her fashions were perfectly sliced and cut, safety pins everywhere. Rodeo didn’t like the Avengers at all.

The Nuns introduced the Avengers at a show in Rodeo, it was a biker club. Penelope was very Art Institute, her fashions were perfectly sliced and cut, safety pins everywhere. Rodeo didn’t like the Avengers at all.

Penelope Houston:

It was maybe our third or fourth show. This is like when Billie Joe Armstrong was five or something. They were biker types, and they wanted to kill us. Not me so much because I was a girl. They wanted to rape me first. But I remember thinking, “Why are we here?”

It was maybe our third or fourth show. This is like when Billie Joe Armstrong was five or something. They were biker types, and they wanted to kill us. Not me so much because I was a girl. They wanted to rape me first. But I remember thinking, “Why are we here?”

Dennis Kernohan:

She had just moved here from Seattle, was a freshman at the Art Institute. She came strolling in, in her little pink poodle outfit, with her little skirt and little purse. Next time I saw her she was in a ripped T-shirt, no bra, totally punked out. Ever since that night in the pink poodle outfit I’ve been madly in love with her.

She had just moved here from Seattle, was a freshman at the Art Institute. She came strolling in, in her little pink poodle outfit, with her little skirt and little purse. Next time I saw her she was in a ripped T-shirt, no bra, totally punked out. Ever since that night in the pink poodle outfit I’ve been madly in love with her.

Joe Rees:

Penelope was so gorgeous. She was always this untouchable kind of person. She wasn’t sociable. She socializes a hell of a lot more now than she ever did then. In those days she was always the mysterious woman. Every guy in the world would love to have been her partner.

Penelope was so gorgeous. She was always this untouchable kind of person. She wasn’t sociable. She socializes a hell of a lot more now than she ever did then. In those days she was always the mysterious woman. Every guy in the world would love to have been her partner.

Aaron Cometbus:

Penelope is the woman every boy

and girl

in the East Bay grew up wanting to marry.

Penelope is the woman every boy

and girl

in the East Bay grew up wanting to marry.

Billie Joe Armstrong:

I got into the Avengers through Aaron. He had these amazing archives and I remember looking at all these old pictures of her.

I got into the Avengers through Aaron. He had these amazing archives and I remember looking at all these old pictures of her.

Sheriff Mike Hennessey:

The Avengers were my favorite group, because of their lyrics. Not just punk rock songs, but political lyrics like “The American in Me,” “We Are the One.” They were just really great message songs for the rebellious youth types. And of course, Penelope Houston was kind of a dream, too.

The Avengers were my favorite group, because of their lyrics. Not just punk rock songs, but political lyrics like “The American in Me,” “We Are the One.” They were just really great message songs for the rebellious youth types. And of course, Penelope Houston was kind of a dream, too.

Dennis Kernohan:

Live, they were incredible. When they were at their peak, they were the best band in the whole scene. Bar none. Better than the Kennedys. They made everyone else look like monkeys. Jimmy Wilsey was a lead guitar player playing bass. Greg could play Black Sabbath in his sleep. And play it faster than anyone else on earth. They were definitely a fake punk band. They were a very good fake punk band. One of the best. But yeah, fake, through and through.

Live, they were incredible. When they were at their peak, they were the best band in the whole scene. Bar none. Better than the Kennedys. They made everyone else look like monkeys. Jimmy Wilsey was a lead guitar player playing bass. Greg could play Black Sabbath in his sleep. And play it faster than anyone else on earth. They were definitely a fake punk band. They were a very good fake punk band. One of the best. But yeah, fake, through and through.

Penelope Houston:

I don’t remember radio being something that we had any access to. Rodney on the ROQ, we did a few times. And then up here, there was one show on KUSF, maybe Howie Klein did it. All week long you waited for this one show to happen. Once in awhile you could get on it. So we started playing other cities.

I don’t remember radio being something that we had any access to. Rodney on the ROQ, we did a few times. And then up here, there was one show on KUSF, maybe Howie Klein did it. All week long you waited for this one show to happen. Once in awhile you could get on it. So we started playing other cities.

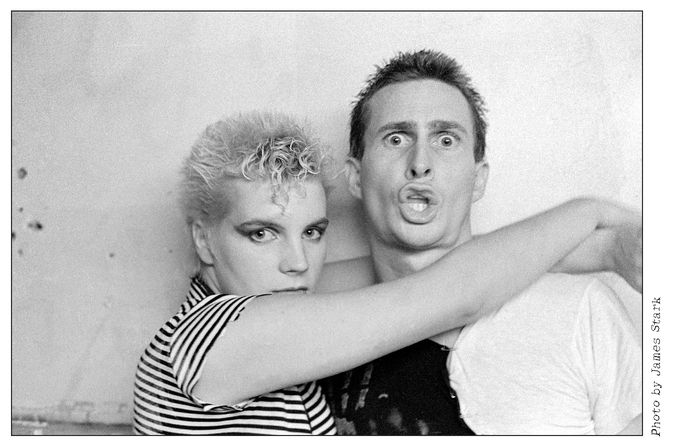

We Are the One: Penelope Houston and Danny Furious of the Avengers

Danny Furious:

We went up to Vancouver in early ’78 to do a show with DOA and the Dishrags. We pulled up to the venue, and this big, beefy, biker type skinhead punk approached our van. Took me by the hand, very politely said, “Hi, I’m Joey Shithead. Welcome to Vancouver!” I nearly pissed my pants.

We went up to Vancouver in early ’78 to do a show with DOA and the Dishrags. We pulled up to the venue, and this big, beefy, biker type skinhead punk approached our van. Took me by the hand, very politely said, “Hi, I’m Joey Shithead. Welcome to Vancouver!” I nearly pissed my pants.

Penelope Houston:

L.A. loved us. They pretended that we were from L.A. because two of our members were from there. We played the Masque a lot, eventually the Whisky. The Go-Gos, X, the Weirdos opened for us. It’s funny, all the people that opened for us. How far they went, and how far we didn’t go.

L.A. loved us. They pretended that we were from L.A. because two of our members were from there. We played the Masque a lot, eventually the Whisky. The Go-Gos, X, the Weirdos opened for us. It’s funny, all the people that opened for us. How far they went, and how far we didn’t go.

Dave Chavez:

Negative Trend, I don’t know how long they were together. I think it was less than two years. If anything, they were one of the heavier bands. They weren’t fast like hardcore became, but they were heavy like hardcore. A very important band, too. They had Will Shatter’s beautiful voice that to this day I still think is one of the greatest voices from any of the scenes.

Negative Trend, I don’t know how long they were together. I think it was less than two years. If anything, they were one of the heavier bands. They weren’t fast like hardcore became, but they were heavy like hardcore. A very important band, too. They had Will Shatter’s beautiful voice that to this day I still think is one of the greatest voices from any of the scenes.

Jello Biafra:

Rozz was the most electrifying part of that band. Our local Iggy.

Rozz was the most electrifying part of that band. Our local Iggy.

Johnny Genocide:

Rozz took the front man persona to the limits, beyond anything anyone was doing at the time.

Rozz took the front man persona to the limits, beyond anything anyone was doing at the time.

Rozz Rezabek:

I was living with these teenage girls in Portland. I had been hanging out with these people that all listened to Mott the Hoople, Bowie, Lou Reed and Iggy, the glitter kind of crowd. There wasn’t really much else. And then all of a sudden the Ramones came up, and we started hearing about stuff over in England. We heard the only place you could even get those records or hear them on the radio was San Francisco. So we had to go.

I was living with these teenage girls in Portland. I had been hanging out with these people that all listened to Mott the Hoople, Bowie, Lou Reed and Iggy, the glitter kind of crowd. There wasn’t really much else. And then all of a sudden the Ramones came up, and we started hearing about stuff over in England. We heard the only place you could even get those records or hear them on the radio was San Francisco. So we had to go.

Me and these three stripper girls, Jane, Pammy and Debbie Sue, headed off to San Francisco together in Debbie’s big old ’56 Buick. Debbie Sue was able to get an apartment and she had already met up with Craig and Will Shatter, they were in a band called Grand Mal.

Will Shatter was always on. He was always kinda snide and sarcastic. The way he would talk kinda sounded like an English accent, almost like a Valley guy. He was from Gilroy. He never let any of that on. To us, he was from England. But we kinda knew he just went over to England.

So Debbie Sue was with Craig, and Will was with Pammy. Pammy and Will had the couch, and I had a pile of cardboard behind the couch. They were like, “This is Rozz from Portland, you gotta put him in the band.”

They were saying, “You can’t be in the band unless you get a punk haircut.” I had kinda long Peter Frampton hair. I’d fought my dad so long to finally be able to grow my hair out. And I was like, “No, then I’m not gonna do it.” Then I did one show with them. I just came in and pushed Don Vinil offstage after about six songs and said, “I’m the new singer.”

Danny Furious:

They managed to pull off a coup at the Mabuhay that night, Rozz jumping stage mid-show and basically not allowing poor Don Vinil to continue.

They managed to pull off a coup at the Mabuhay that night, Rozz jumping stage mid-show and basically not allowing poor Don Vinil to continue.

Rozz Rezabek:

The next time we played, I broke my arm. We played this party with the Avengers at Iguana Studios. All the bands, Dils, Avengers, everybody rehearsed at Iguana Studios for eight dollars an hour. But in the big main room there was a big showcase for Sandy Pearlman, the producer who had just done Blue Oyster Cult’s “Don’t Fear The Reaper.” We thought it was big and important, because we were all like 17 at the time. But it was not really important at all. He was really there just to see the Avengers.

The next time we played, I broke my arm. We played this party with the Avengers at Iguana Studios. All the bands, Dils, Avengers, everybody rehearsed at Iguana Studios for eight dollars an hour. But in the big main room there was a big showcase for Sandy Pearlman, the producer who had just done Blue Oyster Cult’s “Don’t Fear The Reaper.” We thought it was big and important, because we were all like 17 at the time. But it was not really important at all. He was really there just to see the Avengers.

Everybody was getting entangled in all the microphone cords. I tripped over a cord and broke my arm. I went to the hospital and was supposed to be waiting around for the cast. But we were punk rockers, we were impatient. I wanted to get back to the party and see what Sandy Pearlman thought of the band. So I went back. The arm was all fucked up and got broken again, because I didn’t really have a cast on it. I just had these makeshift wraps.

The story got bigger and bigger. It was in Rolling Stone: “In the grand tradition of Iggy Pop, Negative Trend lead singer Rozz, a frisky beanpole of a lad, fell offstage breaking his arm to pieces. And his arm was a shattered bloody wreck.” And then it got picked up in

New York Rocker

. When actually all I did was trip over a cord.

New York Rocker

. When actually all I did was trip over a cord.

We thought it was gonna be this big, big deal, playing in front of Sandy Pearlman. It was years after that, before any punk bands got signed to any labels.

The Avengers were really nice to us. They could really play, just gorgeous music. And same with the Dils. Those guys didn’t see us as a threat. We were just kinda the California Sex Pistols, destroying and breaking furniture. So those guys put us on their bills, to take the pressure off their set or something. It was a nice little chaotic bit of anarchy.

Danny Furious:

Rozz would jump onto tables, knock everyone’s drinks over. Just basically being as obnoxious as possible.

Rozz would jump onto tables, knock everyone’s drinks over. Just basically being as obnoxious as possible.

Rozz Rezabek:

What people liked is that our shows were spontaneous. You went to fuckin’ Crime and the Nuns, you knew exactly what you were gonna get. You knew Jeff Olener was gonna pull out his fake teeth during this song. You knew that Johnny Strike was gonna turn on some stupid cop lights on the back of their amplifiers.

What people liked is that our shows were spontaneous. You went to fuckin’ Crime and the Nuns, you knew exactly what you were gonna get. You knew Jeff Olener was gonna pull out his fake teeth during this song. You knew that Johnny Strike was gonna turn on some stupid cop lights on the back of their amplifiers.

But at a Negative Trend show, you didn’t know if everybody was gonna smash every table and chair in the joint, cover it with an American flag, douse it with gasoline, and start a fire in the middle of the dance floor. We always ended up owing Dirk money, because of the shit that would get destroyed.

Ian MacKaye:

I was quite a student of the West Coast punk scene at the time. Negative Trend, we thought of them as one of the greatest bands that ever existed. The fact that they were San Francisco was just really clear. San Francisco people were really wired. They were jittery, like speed people. And they were kind of crunchy.

I was quite a student of the West Coast punk scene at the time. Negative Trend, we thought of them as one of the greatest bands that ever existed. The fact that they were San Francisco was just really clear. San Francisco people were really wired. They were jittery, like speed people. And they were kind of crunchy.

Rozz Rezabek:

We had a song “Blow Out Kennedy’s Brains Again.” We’d start sloppin’ these big slimy gray cow brains. You could get ’em at any market. You could even get ’em on food stamps. We would use food stamps to buy props.

We had a song “Blow Out Kennedy’s Brains Again.” We’d start sloppin’ these big slimy gray cow brains. You could get ’em at any market. You could even get ’em on food stamps. We would use food stamps to buy props.

Bruce Loose:

I would always have an interaction with Rozz onstage. Grabbing, pulling him onto the ground, we’d be rolling around on the floor. I did a dance called the Worm at the time, where everybody’d be pogoing, and I’d be lying on the floor wriggling around, trying to knock people over. I got stomped on a lot, but, you know.

I would always have an interaction with Rozz onstage. Grabbing, pulling him onto the ground, we’d be rolling around on the floor. I did a dance called the Worm at the time, where everybody’d be pogoing, and I’d be lying on the floor wriggling around, trying to knock people over. I got stomped on a lot, but, you know.

Rozz Rezabek:

We were like the first punk band to tour the West Coast, and when we went up to Seattle we did not disappoint. The club had this eight-foot painting of Marie Osmond in a wedding dress. When we went up onstage we went crazy, and her painting got a hole ripped in a specific place. People took what we were doing and went with it, and went even nutsier. It was a line of crazy Seattle punks gangbanging a painting of Marie Osmond.

We were like the first punk band to tour the West Coast, and when we went up to Seattle we did not disappoint. The club had this eight-foot painting of Marie Osmond in a wedding dress. When we went up onstage we went crazy, and her painting got a hole ripped in a specific place. People took what we were doing and went with it, and went even nutsier. It was a line of crazy Seattle punks gangbanging a painting of Marie Osmond.

When we got outside of San Francisco, we could still shock and awe people. In San Francisco, people had to go further and further. Some sort of B&D situation where they just wanted to take it further further further. There’s no safe word in punk.

Jello Biafra:

Rozz was in so much pain he basically left the band to save himself.

Rozz was in so much pain he basically left the band to save himself.

Other books

The Legend Mackinnon by Donna Kauffman

Contaminated 2: Mercy Mode by Em Garner

A Journey of the Heart Collection by Colleen Coble

Charity Girl by Georgette Heyer

Waiting for Morning by Karen Kingsbury

Cuentos malévolos by Clemente Palma

Questions About Angels by Billy Collins

Confessions of the World's Oldest Shotgun Bride by Gail Hart

Mad Hatter's Holiday by Peter Lovesey

Cocky: A Stepbrother Romance by Emma Johnson