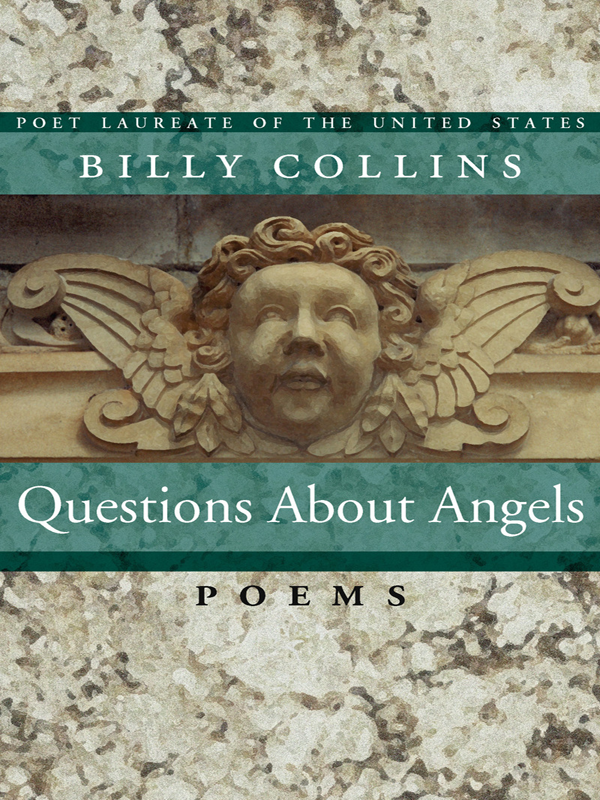

Questions About Angels

Read Questions About Angels Online

Authors: Billy Collins

Â

PITT POETRY SERIES

Ed Ochester, Editor

POEMS

Â

Â

Billy Collins

Â

University of Pittsburgh Press

Published 1999 by the University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, Pa. 15261

Originally published by William Morrow and Company, Inc.

Copyright © 1991, Billy Collins

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Printed on acid-free paper

10 9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Collins, Billy.

Questions about angels : poems / Billy Collins.

p.      cm. â (Pitt poetry series)

ISBN 0-8229-5698-5 (alk. paper)

I. Title. II. Series.

PS3553.047478Q47 1999

811'.54âdc21Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 98-45376

ISBN-13: 978-0-8229-7934-0 (electronic)

Â

for Diane

We do not speak like Petrarch or wear a hat like Spenser

and it is not fourteen lines

like furrows in a small, carefully plowed field

but the picture postcard, a poem on vacation,

that forces us to sing our songs in little rooms

or pour our sentiments into measuring cups.

We write on the back of a waterfall or lake,

adding to the view a caption as conventional

as an Elizabethan woman's heliocentric eyes.

We locate an adjective for the weather.

We announce that we are having a wonderful time.

We express the wish that you were here

and hide the wish that we were where you are,

walking back from the mailbox, your head lowered

as you read and turn the thin message in your hands.

A slice of this place, a length of white beach,

a piazza or carved spires of a cathedral

will pierce the familiar place where you remain,

and you will toss on the table this reversible display:

a few square inches of where we have strayed

and a compression of what we feel.

It is the kind of spring morningâcandid sunlight

elucidating the air, a flower-ruffling breezeâ

that makes me want to begin a history of weather,

a ten-volume elegy for the atmospheres of the past,

the envelopes that have moved around the moving globe.

It will open by examining the cirrus clouds

that are now sweeping over this house into the next state,

and every chapter will step backwards in time

to illustrate the rain that fell on battlefields

and the winds that attended beheadings, coronations.

The snow flurries of Victorian London will be surveyed

along with the gales that blew off Renaissance caps.

The tornadoes of the Middle Ages will be explicated

and the long, overcast days of the Dark Ages.

There will be a section on the frozen nights of antiquity

and on the heat that shimmered in the deserts of the Bible.

The study will be hailed as ambitious and definitive,

for it will cover even the climate before the Flood

when showers moistened Eden and will conclude

with the mysteries of the weather before history

when unseen clouds drifted over an unpeopled world,

when not a soul lay in any of earth's meadows gazing up

at the passing of enormous faces and animal shapes,

his jacket bunched into a pillow, an open book on his chest.

I can see them standing politely on the wide pages

that I was still learning to turn,

Jane in a blue jumper, Dick with his crayon-brown hair,

playing with a ball or exploring the cosmos

of the backyard, unaware they are the first characters,

the boy and girl who begin fiction.

Beyond the simple illustration of their neighborhood

the other protagonists were waiting in a huddle:

frightening Heathcliff, frightened Pip, Nick Adams

carrying a fishing rod. Emma Bovary riding into Rouen.

But I would read about the perfect boy and his sister

even before I would read about Adam and Eve, garden and gate,

and before I heard the name Gutenberg, the type

of their simple talk was moving into my focusing eyes.

It was always Saturday and he and she

were always pointing at something and shouting “Look!”

pointing at the dog, the bicycle, or at their father

as he pushed a hand mower over the lawn,

waving at aproned mother framed in the kitchen doorway,

pointing toward the sky, pointing at each other.

They wanted us to look but we had looked already

and seen the shaded lawn, the wagon, the postman.

We had seen the dog, walked, watered and fed the animal,

and now it was time to discover the infinite, clicking

permutations of the alphabet's small and capital letters.

Alphabetical ourselves in the rows of classroom desks,

we were forgetting how to look, learning how to read.

The emotion is to be found in the clouds,

not in the green solids of the sloping hills

or even in the gray signatures of rivers,

according to Constable, who was a student of clouds

and filled shelves of sketchbooks with their motion,

their lofty gesturing and sudden implication of weather.

Outdoors, he must have looked up thousands of times,

his pencil trying to keep pace with their high voyaging

and the silent commotion of their eddying and flow.

Clouds would move beyond the outlines he would draw

as they moved within themselves, tumbling into their centers

and swirling off at the burning edges in vapors

to dissipate into the universal blue of the sky.

In photographs we can stop all this movement now

long enough to tag them with their Latin names.

Cirrus, nimbus, stratocumulusâ

dizzying, romantic, authoritarianâ

they bear their titles over the schoolhouses below

where their shapes and meanings are memorized.

High on the soft blue canvases of Constable

they are stuck in pigment but his clouds appear

to be moving still in the wind of his brush,

inching out of England and the nineteenth century

and sailing over these meadows where I am walking,

bareheaded beneath this cupola of motion,

my thoughts arranged like paint on a high blue ceiling.