Full House (3 page)

Why, then, do we continually portray this pitifully limited picture of one little stream in vertebrate life as a model for the whole multicellular pageant? Yet how many of us have ever looked at such a standard iconographic sequence and raised any question about its basic veracity? The usual iconography seems so right, so factual. I shall argue in this book that our unquestioning approbation of such a scheme provides our culture’s most prominent example of a more extensive fallacy in reasoning about trends—a focus on particulars or abstractions (often biased examples like the lineage of Homo sapiens), egregiously selected from a totality because we perceive these limited and uncharacteristic examples as moving somewhere—when we should be studying variation in the entire system (the "full house" of my title) and its changing pattern of spread through time. I will emphasize the set of trends that inspires our greatest interest—supposed improvements through time. And I shall illustrate an unconventional mode of interpretation that seems obvious once stated, but rarely enters our mental framework—trends properly viewed as results of expanding or contracting variation, rather than concrete entities moving in a definite direction. This book, in other words, treats the "spread of excellence," or trends to improvement best interpreted as expanding or contracting variation.

2

Darwin Amidst the Spin Doctors

Biting the Fourth Freudian Bullet

I have often had occasion to quote Freud’s incisive, almost rueful, observation that all major revolutions in the history of science have as their common theme, amidst such diversity, the successive dethronement of human arrogance from one pillar after another of our previous cosmic assurance. Freud mentions three such incidents: We once thought that we lived on the central body of a limited universe until Copernicus, Galileo, and Newton identified the earth as a tiny satellite to a marginal star. We then comforted ourselves by imagining that God had nevertheless chosen this peripheral location for creating a unique organism in His image— until Darwin came along and "relegated us to descent from an animal world." We then sought solace in our rational minds until, as Freud notes in one of the least modest statements of intellectual history, psychology discovered the unconscious.

Freud’s statement is acute, but he left out several important revolutions in the pedestal-smashing mode (I offer no criticism of Freud’s insight here, for he tried only to illustrate the process, not to provide an exhaustive list). In particular, he omitted the major contribution made to this sequence by my own field of geology and paleontology—the temporal counterpart to Copernicus’s spatial discoveries. The biblical story, read literally, was so comforting: an earth only a few thousand years old, and occupied for all but the first five days by humans as dominant living creatures. The history of the earth becomes coextensive with the story of human life. Why not, then, interpret the physical universe as existing for and because of us?

But paleontologists then discovered "deep time," in John McPhee’s felicitous phrase. The earth is billions of years old, receding as far into time as the visible universe extends into space. Time itself poses no Freudian threat, for if human history had occupied all these billions, then we might have increased our arrogance by longer hegemony over the planet. The Freudian dethronement occurred when paleontologists revealed that human existence only fills the last micromoment of planetary time—an inch or two of the cosmic mile, a minute or two in the cosmic year. This phenomenal restriction of human time posed an obvious threat, especially in conjunction with Freud’s second, or Darwinian, revolution. For such a limitation has a "plain meaning"—and plain meanings are usually correct (even though many of our most fascinating intellectual revolutions celebrate the defeat of apparently obvious interpretations): If we are but a tiny twig on the floridly arborescent bush of life, and if our twig branched off just a geological moment ago, then perhaps we are not a predictable result of an inherently progressive process (the vaunted trend to progress in life’s history); perhaps we are, whatever our glories and accomplishments, a momentary cosmic accident that would never arise again if the tree of life could be replanted from seed and regrown under similar conditions.

In fact, I would argue that all these "plain meanings" are true, and that we should revel in our newfound status and attendant need to construct meanings by and for ourselves—but this is another story for another time. I called this other story Wonderful Life (Gould, 1989). The theme for the present book, something of a philosophical "companion volume," is Full House. For now, I only point out that this plain meaning is profoundly antithetical to some of the deepest social beliefs and psychological comforts of Western life—and that popular culture has therefore been unwilling to bite this fourth Freudian bullet.

Only two options seem logically available in our attempted denial. We might, first of all, continue to espouse biblical literalism and insist that the earth is but a few thousand years old, with humans created by God just a few days after the inception of planetary time. But such mythology is not an option for thinking people, who must respect the basic factuality of both time’s immensity and evolution’s veracity. We have therefore fallen back upon a second mode of special pleading

—

Darwin among the spin doctors. How can we tell the story of evolution with a slant that can validate traditional human arrogance?

If we wish both to admit the restriction of human time to the last micromoment of planetary time, and to continue our traditional support for our own cosmic importance, then we have to put a spin on the tale of evolution. I believe that such a spin would seem ridiculous prima facie to the metaphorical creature so often invoked in literary works to symbolize utter objectivity—the dispassionate and intelligent visitor from Mars who arrives to observe our planet for the first time, and comes freighted with no a priori expectations about earthly life. Yet we have been caught in this particular spin so long and so deeply that we do not grasp the patent absurdity of our traditional argument.

This positive spin rests upon the fallacy that evolution embodies a fundamental trend or thrust leading to a primary and defining result, one feature that stands out above all else as an epitome of life’s history. That crucial feature, of course, is progress—operationally defined in many different ways

1

as a tendency for life to increase in anatomical complexity, or neurological elaboration, or size and flexibility of behavioral repertoire, or any criterion obviously concocted (if we would only be honest and introspective enough about our motives) to place Homo sapiens atop a supposed heap.

We might canvass a range of historians, psychologists, theologians, and sociologists for their own distinctive views on why we feel such a need to validate our existence as a predictable cosmic preference. I can speak only from my own perspective as a paleontologist in the light of the fourth Freudian revolution: We are driven to view evolution’s thrust as predictable and progressive in order to place a positive spin upon geology’s most frightening fact—the restriction of human existence to the last sliver of earthly time. With such a spin, our limited time no longer threatens our universal importance. We may have occupied only the most recent moment as Homo sapiens, but if several billion preceding years displayed an overarching trend that sensibly culminated in our mental evolution, then our eventual origin has been implicit from the beginning of time. In one important sense, we have been around from the start. In principio erat verbum.

We may easily designate belief in progress as a potential bias, but some biases are true: my utterly subjective rooting preferences led me to love the Yankees during the 1950s, but they were also, objectively, the best team in baseball. Why should we suspect that progress, as the defining thrust of life’s history, is not true? After all, and quite apart from our wishes, doesn’t life manifestly become more complex? How can such a trend be denied in the light of paleontology’s most salient fact: In the beginning, 3.5 billion years ago, all living organisms were single cells of the simplest sort, bacteria and their cousins; now we have dung beetles, sea-horses, petunias, and people. You would have to be a particularly refractory curmudgeon, one of those annoying characters who loves verbal trickery and empty argument for its own sake, to deny the obvious statement that progress stands out as the major pattern of life’s history.

This book tries to show that progress is, nonetheless, a delusion based on social prejudice and psychological hope engendered by our unwillingness to accept the plain (and true) meaning of the fourth Freudian revolution. I shall not make my case by denying the basic fact just presented: Long ago, only bacteria populated the earth; now, a much broader diversity includes Homo sapiens. I shall argue instead that we have been thinking about this basic fact in a prejudiced and unfruitful way—and that a radically different approach to trends, one that requires a revision of even more basic mental habits dating at least to Plato, offers a more profitable framework. This new vantage point will also help us to understand a wide range of puzzling issues from the disappearance of 0.400 hitting in baseball to the absence of modern Mozarts and Beethovens.

Can We Finally Complete Darwin’s Revolution?

The bias of progress expresses itself in various ways, from naive versions of pop culture to sophisticated accounts in the most technical publications. I do not, of course, claim that all, or even many, people accept the maximally simplistic account of a single ladder, with humans on top—although this imagery remains widespread, even in professional journals. Most writers who have studied some evolutionary biology understand that evolution is a copiously branching bush with innumerable present outcomes, not a highway or a ladder with one summit. They therefore recognize that progress must be construed as a broad, overall, average tendency (with many stable lineages "failing" to get the "message" and retaining fairly simple form through the ages).

Nonetheless, however presented, and however much the sillier versions may be satirized and ridiculed, claims and metaphors about evolution as progress continue to dominate all our literatures—a testimony to the strength of this primary bias. I present a few items, almost randomly selected from my burgeoning files:

From Sports Illustrated, August 6, 1990, Denver Broncos veteran Karl Mecklenburg, on being shifted from defensive end to inside linebacker to a new position as outside linebacker: "I’m moving right up the evolutionary ladder."

From a correspondent, writing from Maine on January 18, 1987, and puzzled because he cannot spot the fallacy in a creationist tract: The pamphlet "shows that well dated finds of many species of man show no advancement within a species over the thousands of years the species existed. Also many species appear to have existed concurrently. Both these finds contradict the precepts of evolution which insists each species advances towards the next higher."

From another correspondent, in New Jersey (December 22, 1992), a professional scientist this time, expressing his understanding that life as a totality, not just selected lineages at pinnacles of their groups, should progress through time: "I assume that as evolution proceeds, a greater and greater degree of specialization occurs with regard to structure and physiological activity. After a billion years or more of biological evolution I would think that the extant species are relatively highly specialized."

From a correspondent in England on June 16, 1992, really putting it on the line: "Life has a sort of ’built-in’ drive towards complexity, matched by no drive to de-complexity.... Human consciousness was inevitable once things got started on Complexity Road in the first place."

From a leading high school biology textbook, published in 1966, and providing a classic example of a false inference (the first sentence) drawn from a genuine fact (the second sentence): "Most descriptions of the pattern of evolution depend upon the assumption that organisms tend to become more and more complicated as they evolve. If this assumption is correct, there would have been a time in the past when the earth was inhabited only by simple organisms."

From America’s leading professional journal, Science, in July 1993: An article titled "Tracing the Immune System’s Evolutionary History" rests upon the peculiar premise, intelligible only if "everybody knows" about life’s progress through time, that we should be surprised to discover sophisticated immune devices in "the lower organisms" (their phrase, not mine). The article claims to be reporting a remarkable insight: "the immune system in simpler organisms isn’t just a less sophisticated version of our own." (Why should anyone have ever held such a view of "others" as basically "less than us," especially when the "simpler organisms" under discussion are arthropods with 500 million years of evolutionary separation from vertebrates, and when all scientists recognize the remarkable diversity and complexity of chemical defense systems maintained by many insects?) The article also expresses surprise that "creatures as far down the evolutionary ladder as sponges can recognize tissue from other species." If our leading professional journal still uses such imagery about evolutionary ladders, why should we laugh at Mr. Mecklenburg for his identical metaphor?

The allure of this conventional imagery is so great that I have fallen into the trap myself—by presenting my examples as an ascending ladder from the central pop icon of a sports hero, through letters of increasing sophistication, to textbooks, to an article in Science. Yet the last shall be first, and my linear sequence bends into a circle of error, as both my initial and final examples misuse the identical phrase about an "evolutionary ladder." At least the linebacker was trying to be funny!

These lists of error could go on forever, but let me close this section with two striking examples representing the pinnacle (there we go with progress metaphors again) of fame and achievement in the domains of popular and professional life.

Popular culture’s leading version: Psychologist M. Scott Peck’s The Road Less Traveled, first published in 1978, must be the greatest success in the history of our distinctive and immensely popular genre of "how-to" treatises on personal growth. This book has been on the New York Times best-seller list for more than six hundred weeks, placing itself so far in first place for total sales that we need not contemplate any challenge in our lifetime. Peck’s book includes a section titled "The Miracle of Evolution" (pages 263-68).

Peck begins his discussion with a classic misunderstanding of the second law of thermodynamics:

The most striking feature of the process of physical evolution is that it is a miracle. Given what we understand of the universe, evolution should not occur; the phenomenon should not exist at all. One of the basic natural laws is the second law of thermodynamics, which states that energy naturally flows from a state of greater organization to a state of lesser organization.... In other words, the universe is in a process of winding down.

But this statement of the second law, usually portrayed as increase of entropy (or disorder) through time, applies only to closed systems that receive no inputs of new energy from exterior sources. The earth is not a closed system; our planet is continually bathed by massive influxes of solar energy, and earthly order may therefore increase without violating any natural law. (The solar system as a whole may be construed as closed and therefore subject to the second law. Disorder does increase in the entire system as the sun uses up fuel, and will ultimately explode. But this final fate does not preclude a long and local buildup of order in that little corner of totality called the earth.)

Peck designates evolution as miraculous for violating the second law in displaying a primary thrust toward progress through time:

The process of evolution has been a development of organisms from lower to higher and higher states of complexity, differentiation, and organization.... [Peck then writes, in turn, about a virus, a bacterium, a paramecium, a sponge, an insect, and a fish—as if this motley order represented an evolutionary sequence. He continues:] And so it goes, up the scale of evolution, a scale of increasing complexity and organization and differentiation, with man who possesses an enormous cerebral cortex and extraordinarily complex behavior patterns, being, as far as we can tell, at the top. I state that the process of evolution is a miracle, because insofar as it is a process of increasing organization and differentiation it runs counter to natural law.

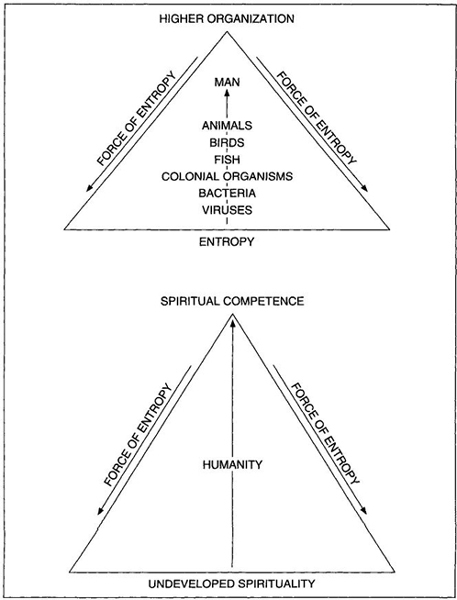

Peck then summarizes his view as a diagram (redrawn here as Figure 2), a stunning epitome of the grand error that the bias of progress imposes upon us. He recognizes the primary fact of nature that stands so strongly against any simplistic view of progress (and, as I shall show later in this book, debars the subtler versions as well)—rarity of the highest form (humans) versus ubiquity of the lowest (bacteria). If progress is so damned good, why don’t we see more of it?

Peck tries to pry victory from the jaws of defeat by portraying life as thrusting upward against an entropic downward tug:

The process of evolution can be diagrammed by a pyramid, with man, the most complex but least numerous organism, at the apex, and viruses, the most numerous but least complex organisms, at the base. The apex is thrusting out, up, forward against the force of entropy. Inside the pyramid I have placed an arrow to symbolize this thrusting evolutionary force, the "something" that has so successfully and consistently defied "natural law" over millions upon millions of generations and that must itself represent natural law as yet undefined.

Note how this simple diagram encompasses all the major errors of progressivist bias. First, although Peck supposedly rejects the most naive version of life’s ladder, he places an explicit linear array right under his apex of progress as the motor of upward thrusting. Two features of this reintroduced ladder reveal Peck’s lack of attention and sympathy for natural history and life’s diversity. I am, I confess, galled by the insouciant sweep that places only "colonial organisms" into the enormous domain between bacteria and vertebrates—where they must stand for all eukaryotic unicellular organisms and all multicellular invertebrates as well, though neither category includes many colonial creatures! But I am equally cha

-

grined by Peck’s names for the prehuman vertebrate sequence: fish, birds, and animals. I know that fish gotta swim and birds gotta fly, but I certainly thought that they, and not only mammals, were called animals.

Second, the model of life’s upward thrust versus inorganic nature’s downward tug allows Peck to view progress as evolution’s most powerful and universal trend, even against the observation that most organisms don’t get very far along the preferred path: against so powerful an adversary as entropy, all life must stand and shove together from the base, so that the accumulating force will push a favored few right up to the top and out. Squeeze your toothpaste tube from the bottom, just as Mom and the dentist always admonished (and so few of us do), and the pressure of the whole mass will allow a little stream to reach an utmost goal of human service at the top.

FIGURE 2 Two biased views of evolution as progress from M. Scott Peck’s best-selling The Road Less Traveled. Above, the supposed pyramid of life’s upwardly driving complexity. Below, the same scheme applied to the supposed development of human spiritual competence.

Peck ends this section with a crescendo based on one of those forced and fatuous images that sets my generally negative attitude toward this genre of books. Human life and striving become a microcosm of life’s overall trend to progress. The force of entropy (also identified as our own lethargy) still pushes down, but love, standing in for the drive of progress (or are they the same?), drives us from the low state of "undeveloped spirituality" toward the acme, or pyramidal point, of "spiritual competence." Peck concludes by writing, "Love, the extension of the self, is the very act of evolution. It is evolution in progress. The evolutionary force, present in all of life, manifests itself in mankind as human love. Among humanity love is the miraculous force that defies the natural law of entropy." Sounds mighty nice and cozy, but I’ll be damned if it means anything.

A similar vision from the professional heights. My colleague E. O. Wilson is one of the world’s greatest natural historians. If anyone understands the meaning and status of species and their interrelationships, this unparalleled expert on ants, and tireless crusader for preservation of biodiversity, should be the paragon. I enjoyed his book The Diversity of Life (1992), and reviewed it favorably in the leading British journal Nature (Gould, 1993). Ed and I have our disagreements about a variety of issues, from sociobiology to arcana of Darwinian theory, but we ought to be allied on the myth of progress, if only because success in our profession’s common battle for preserving biodiversity requires a reorientation of human attitudes toward other species—from little care and maximal exploitation to interest, love, and respect. How can this change occur if we continue to view ourselves as better than all others by cosmic design?

Nonetheless, Wilson uses the oldest imagery of the progressivist view in epitomizing the direction of life’s history as a series of formal Ages (with uppercase letters, no less)—a system used by virtually all popular works and textbooks in my youth, but largely abandoned (I thought), for reform so often affects language first (as in our eternal debates about political correctness and the proper names for groups and genders), and concepts only later:

They [arthropods as the first land animals] were followed by the amphibians, evolved from lobe-finned fishes, and a burst of land vertebrates, relative giants among land animals, to inaugurate the Age of Reptiles. Next came the Age of Mammals and finally the Age of Man.

These words do not represent a rhetorical slip into comfortable, if antiquated, phraseology, for Wilson also provides his explicit defense of progress, ending with a line that I found almost chilling:

Many reversals have occurred along the way, but the overall average across the history of life has moved from the simple and few to the more complex and numerous. During the past billion years, animals as a whole evolved upward in body size, feeding and defensive techniques, brain and behavioral complexity, social organization, and precision of environmental control.... Progress, then, is a property of the evolution of life as a whole by almost any conceivable intuitive standard, including the acquisition of goals and intentions in the behavior of animals. It makes little sense to judge it irrelevant. Attentive to the adjuration of C. S. Peirce, let us not pretend to deny in our philosophy what we know in our hearts to be true.