Fringe Florida: Travels Among Mud Boggers, Furries, Ufologists, Nudists, and Other Lovers of Unconventional Lifestyles (6 page)

Authors: Lynn Waddell

Tags: #History, #Social Science, #United States, #State & Local, #South (AL; AR; FL; GA; KY; LA; MS; NC; SC; TN; VA; WV), #Cultural, #Anthropology

the cub to the Outpost. Terine admonishes, “She said she would come

alF

visit him, but she never has.”

F

Not all big-cat lovers have the fortitude to grow old with a tiger or

o e

the time to volunteer at a sanctuary, but Florida’s wannabe neo-me-

ire

nagerists can be just as committed in their fandom. Consider the infa-

gan

mous Bobo-Tarzan incident: The 600-pound Siberian-Bengal mix was

eM

the pet of a former Spanish Tarzan actor, who apparently had trouble

52

escaping his role. (He also played a biker who mutates into a monster

turkey and goes after drug dealers in the 1972 B-movie

Blood

Freak

.)

Steve Sipek was able to keep big cats because he owned them before the

state outlawed them as pets. Up until 2012, he lived, swam, and slept

with them at his Loxahatchee compound. He views himself as having

a special gift, a “sixth sense,” that allows him to communicate with the

cats, he told ABC News. Call him a tiger whisperer.

His abilities failed him in 2004 when Bobo escaped and roamed his

south Florida neighborhood for more than twenty-four hours. Neigh-

bors were terrified, but the bigger outcry came after a wildlife officer

shot and killed Bobo. The officer said the cat growled and lunged at

him. Tarzan didn’t believe it and called the shooting a murder. Hordes

of tiger fans agreed and mourned Bobo outside Tarzan’s gate. They left

a shrine of signs, wooden crosses, flowers, and giant posters of the

cat. They held candlelight vigils. They attended Bobo’s burial service,

which was complete with a priest, guest book, and a hearse. Later a fan

compiled a YouTube.com memorial video, a Bobo photo montage set

to Lionel Richey’s “Just for You.” The FFWCC got so many angry calls

from outraged big-cat lovers that supervisors warned unarmed FFWCC

biologists not to wear their uniforms in the field. The wildlife officer

who shot Bobo in self-defense? He got death threats.

proof

Seven years later, big-cat people still grieve for Bobo and berate the

FFWCC on Internet message boards. Given the intensity of the linger-

ing outrage, I dare not bring up Bobo to my Fla-zoon felidae guide.

“People just don’t realize what they are getting themselves into,”

Terine laments again as we trace our path back to the entrance. “They

may mean well, but they just don’t stop and think. If they only just

looked it up on the Internet and read just a little bit. A wild animal isn’t

like having a dog or a cat.”

Most sanctuaries preach this same message. The sentiment, how-

ever earnest, often comes across like daredevil Evel Knievel’s warn-

ing—“Don’t try this at home, kids”—before he drove his rocket-cycle

ad

off the edge of Snake River Canyon.

ir

Back where we started the tour, an adorable lion cub about the size

olF

and color of a large golden retriever bounces back and forth inside a

eg

small cage. He rears up on his hind legs and puts his front paws on the

nir

gate like a puppy in a pet store begging for attention. Terine laughs.

F

“That’s my Mus. He wants to play.”

62

Mus (pronounced Moose and short for Musafa) lives with Terine.

The black-maned lion cub isn’t a rescue. A local breeder bought him

from a Kansas breeder when the cub was only five weeks old. Terine is

just caring for Mus until he’s old enough to breed.

He comes to work with her and sleeps in her bed at night. She had a

live-in boyfriend when she got Mus, but says, “He was jealous of Mus,

so I got rid of him.”

When Mus was smaller, he followed Terine around as she went

about her chores at the refuge. At seven months, his paws are already

bigger than a man’s palm, so he stays inside a pen or on a leash.

Terine leads him out of the cage. He’s full of personality and seems

to smile at me. I admit that the urge to pet him is strong because he

acts more like a puppy than a ferocious lion. Terine sits on top of a

wooden picnic table and poses with him for some photos. She leans

down and kisses him on the mouth. When she diverts her attention,

he bats at her playfully with his mitt. She pushes it away while continu-

ing to talk; he doesn’t give up. Mus probably already weighs as much as

Terine. When she leads him around in the grass and stops for a second,

he tugs, jerking her to the side with each pull.

Mus is a feline celebrity. He’s been on

Jimmy

Kimmel

Live

and NBC’s

Today

Show

. On one trip, a network put him and Terine up in a suite

proof

at the luxurious Ritz Carlton in New York. The hotel treated Mus like

royalty, and he had his own bed. Terine walked him in the posh hotel’s

designated doggie area and laughs that it freaked out some chihuahua

owners.

This raises some fundamental hygiene questions: Where does Mus

go to the bathroom?

As a small cub he used her cat’s litter box, but now he goes outside

like her dog, she says.

Mus is male, and by instinct mature male felines spray urine to

sno

mark their territory. Lions are super-soakers; they can spray urine up

oz-

to 10 feet away and are notorious for aiming at people. Terine says

alF

Mus doesn’t spray, and she doesn’t think he will because he hasn’t been

F

around a male feline that does. “I think it’s a learned behavior.”

o e

I make a mental note to check back with her on that in a year.

ire

After leaving the Outpost with the image of Terine kissing Mus

gan

etched in my memory, I think of Florida big-cat rescuer Carole Baskin,

eM

and her former self, Carole Lewis.

72

Cat Fights

More than a decade ago Carole shared her bed with a wild feline. She

has since transformed into Florida’s fiercest critic of the exotic-pet

trade. The Tampa breeding facility and refuge she cofounded in the

mid-1990s is now Big Cat Rescue (BCR), a “no-touch” retirement home

for about 115 big cats and a few other exotics. She argues that playing

with cubs gives people the idea that they can be pets and perpetuates

captive breeding of the cats when there aren’t enough decent facilities

to keep them now. “We have to turn away more than fifty a month,”

she says. Several of Florida’s roadside zoo and backyard sanctuary op-

erators also breed and sell big cats to help support their operation, or,

they say, to “preserve the species.” All of which makes Carole extend

her claws. “It’s just obscene to consider your facility a sanctuary when

you are breeding animals that have nowhere to go.”

Carole’s dream is that big cats will one day exist only in the wild, not

in sanctuaries like hers, not even in big accredited zoos. Her methods

can be prickly. She’s penned venomous articles and blogs online about

many of Florida’s backyard zoos and sanctuaries, characterizing them

as thinly veiled personal menageries with operators who delude them-

selves into thinking they are martyrs.

proof

She’s posted critical USDA inspection reports of other big-cat parks

and refuges. She mailed 1,500 letters to the neighbors of licensees,

notifying them of dangerous wildlife living next door and upcoming

public hearings about new regulations. She’s lobbied Washington and

Tallahassee for stricter laws on captive wild animals, shared her views

with national publications, and enraged other exotic-animal owners in

Florida and beyond.

“She’s the most hated person in Florida among exotics owners,” says

one Florida big-cat exhibitor, summing up what I’ve heard from several

others.

Big-cat people can be a little catty with one another, or play rough,

ad

especially when their pride is threatened. Many, like Carole, are multi-

ir

media savvy; cat fights often take place in a virtual arena.

olF

An anonymous critic devotes an entire blog, “Big Cat Rescue Lies,” to

eg

pointing out exaggerations in BCR’s cat stories, along with character-

nir

izing Carole as a “sociopath.”

F

Ticked off by Carole’s criticism of white-tiger breeders in a

Newsweek

82

article, the director of Feline Conservation Federation, which caters to

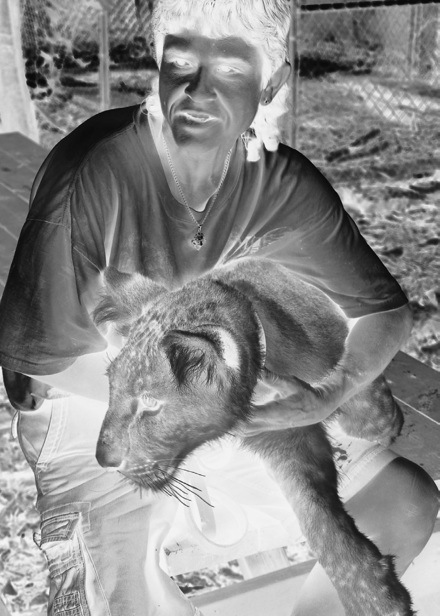

Terine, an Everglades Out-

post Wildlife Rescue worker,

warns against exotic animal

ownership as she tries to

control Mus, the young Afri-

can lion that lives with her.

Photo by James Harvey.

proof

pet owners and breeders, posted a scathing opus: “Rebuttal to Carole

Baskin’s Campaign of Hatred.”

Her most colorful critic is Oklahoma exotic-animal-park-operator

Joe Exotic, whom Carole has vigorously lobbied to shut down. His You-

tube.com series rants about everything from where Carole got her cats

to the size of her ass. He’s posted more than seventy lengthy expletive-

sno

filled diatribes, a few with his talking mouth and bulging eyes morphed

oz-

onto the face of a baby. Yes, a grown man’s teeth in the mouth of a babe

alF

saying Carole’s claims are “a big old thing of crawdad bullshit.”

F

Carole’s well aware that she has armies of enemies. The tires on

o e

BCR’s vans have been slashed more than once; she’s asked security to

ire

escort her out of FFWCC meetings. One refuge owner she targeted, a

gan

man from Seminole who rides around with his pet tiger in the back of

eM

his pickup, regularly protests at her glitzy Fur Ball fund-raisers. Car-

9

ole says hostility peaked when she lobbied to require owners of the

2

twenty-four most dangerous exotics to get a ten-thousand-dollar

surety bond. The bill was especially controversial because it also out-

lawed pythons as pets. “People would come up screaming at me and

threatening me, especially the snake people. They’re whack jobs.” Many

of her detractors, naturally, make the same assessment of her.

Invariably, their main criticism is that she’s a hypocrite. They point

out that she has a sanctuary and that she and her late husband once

bred and sold wild cats. They emphasize that many of the animals she

claims that she “rescued” were once her pets. All true.

Carole insists that was only the case in the 1990s, when she was

married to Don Lewis, a man whose mysterious disappearance has also

been juicy fodder for her foes. Wildman Joe Exotic even offers a ten-

thousand-dollar reward for information about Don’s disappearance.

I first met Carole in 1999 while writing a story for a local alterna-

tive newspaper about her eccentric missing husband. A shapely woman

with big, blue eyes, she met me in leopard print leggings and invited

me into her small, hodgepodge home that also served as the sanctuary

office. Her personal space was limited to a cluttered bedroom with a

tiger print spread on a bed she had shared with a bobcat.

Don made his millions dealing in tax-deed property and from sell-

ing RVs and treasures he plucked from dumpsters. He was a trader to

proof

the core; everything was a commodity including, sometimes, their big

cats. Carole says they didn’t set out to be big-cat owners. They went to

an animal auction to buy llamas and were horrified to see a young bob-

cat on a leash. They bought it, and Don loved it as his pet. Later at an

auction in Minnesota, they bought fifty-six baby bobcats that she says

were destined for a fur farm. “We bought them all to keep them from

being killed,” she says. She admits they sold them as pets. “We didn’t

know how stupid it was. We made an awful lot of mistakes over the

years. The only people who could offer advice were the breeders.”

They raised the cats on 40 acres down a dirt road in what was then

a semi-rural area on the fringe of Tampa. They lived in a small, older

ad

house surrounded by cat cages and called it Wildlife on Easy Street.

ir

During those years, Carole says she awakened to the ugliness of the