Fringe Florida: Travels Among Mud Boggers, Furries, Ufologists, Nudists, and Other Lovers of Unconventional Lifestyles (40 page)

Authors: Lynn Waddell

Tags: #History, #Social Science, #United States, #State & Local, #South (AL; AR; FL; GA; KY; LA; MS; NC; SC; TN; VA; WV), #Cultural, #Anthropology

would mess up, but these two girls were pushing me on.” He found that

carnival machismo only goes so far with the ladies. When he got off the

stage, the girls were gone.

As a teen, Butch bought groceries for the “Half-Girl,” Jeanie To-

maini. “She climbed up barstools then hopped around from one to an-

other. She had them all over the kitchen. She was strong as an ox and

proof

one of the nicest people you would ever meet.” She used to tip him

twenty dollars back when a fiver was considered generous.

He paints a romantic image of what the community used to be,

which is a little hard to believe given what it is now. He says as a kid

he’d walk to the Alafia River and catch fish all day. He’d go swimming at

then-undeveloped Apollo Beach, and claims that Tampa Bay was clear

enough to see the bottom.

His current neighbor owns fair rides, but Butch says there aren’t

na

many carnies around these days. He estimates in the heyday that tent

MWo

performers and ride operators represented about a fourth of the com-

hs

munity; now, maybe 5 percent. “It’s just not what it used to be,” he says.

tsa

“I won’t even fish in the river anymore it’s so polluted.”

l

As he goes off on a tangent about fishing, his friend Bill sidles up to

s’n

the bar. Another retired veteran, Bill still sports a flat-top and a faded

Wot

tattoo that looks like he got it in a seaport. With a southern twang he

Woh

calls out to a passing waitress, “Hey, I’ve got you down for a slab. Do

s

you want some sides?” She answers, and he scribbles it down on a piece

11

of paper.

2

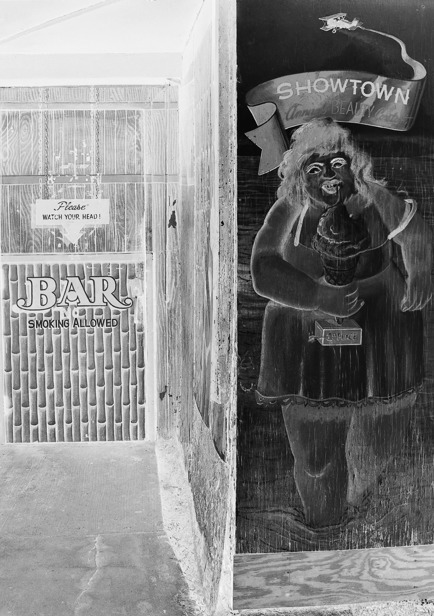

Showtown USA Bar &

Restaurant’s painted

midget door is almost

believable, especially

when you consider

that Gibsonton was

once filled with

retired sideshow

performers. Photo by

author.

proof

Bill is from Alabama, too, so we have a brief bonding about southern

barbeque, fried catfish, and fresh crappie. Meanwhile Butch tells the

female bartender, “We’ve got you down for a Boston butt. Do you want

any sides? We’ve got baked beans and they are goooood.”

These guys are actually selling their home-cooked food inside a

restaurant.

adi

When I ask about it, Bill whips out a business card: B&B Barbeque.

ro

They smoke pork, cook baked beans, and make coleslaw, all at home on

lF

order. It sounds like they’ll be smoking a barnyard the next day. “Hey,

egn

do you want some ribs or a Boston butt?” Butch asks. “It’s the real

irF

thing. We smoke it slow and we make our own sauce.”

The bartender overhears and adds, “It’s good. They’ve brought me

212

some before.”

My stomach growls and I cave to the fantasy of a true southern bar-

beque sandwich. He puts me down for a Boston butt. I resist their pitch

on the sides. Butch says to call and he’ll walk it over to the bar the next

night. “I just live down the road, within walking distance.”

I drive away wondering why I had just agreed to buy a home-smoked

pork roast from a stranger I’d just met in a smoky sideshow bar. Every-

one seems to have a pitch in Gibtown.

Police! Hooves Up!

After leaving phone messages and Facebook e-mails, I get a call back

from the King of the Sideshow. “This is Ward Hall,” he declares. He’s

says he’s back in town for some speaking engagements, all sounding

very official, but graciously agrees to meet with me at his house the

next week. He goes on to give incredibly detailed directions, the type

people gave before maps. He warns to call an hour before to make sure

he’s there. I suspect he needs the reminder.

Preparing for our meeting, I discover that while his show may be the

only traveling 10-in-1, it’s not the only traveling carnival sideshow left

in America or Florida. There are various classifications of sideshows,

and operators sometimes get in pissing matches over definitions, and

proof

who can claim this or that. Regardless, few sideshows exist of any kind.

One operator says there are as few as seven and three of those are based

in Florida.

Jim Zajicek of Tampa owns Big Circus Sideshow. His is a freak ani-

mal show. At fifty, he’s still a relative youngster among sideshow op-

erators. Like Ward, he’s trying to keep the traditional style alive. He’s

got the classic 80-foot wall of sideshow banners and a carnival shtick

so retro he could actually be a time-traveler. He’s tall, slim, and wears

na

heavy framed glasses, bowties, and vintage hats. His bally voice is deep

MWo

and rhythmic in a Rod Serling

Twilight

Zone

way. No sequins—Jim’s

hs

not one for flash.

tsa

We meet for dinner near his home in Seminole Heights, a regentri-

l

fied neighborhood in Tampa. He’s hitting the road the next morning

s’n

bound for a Texas State Fair and will bounce from one to another as

Wot

far away as Utah for the next seven months. Out of costume in a plaid

Woh

shirt and jeans, Jim blends in with the casually dressed yuppies. Con-

s

trary to his bally persona, offstage he wastes few words.

31

Jim’s show is mainly a museum. He only has a few live deformed

2

animals—a six-legged steer, a five-legged sheep, an albino turtle, a tiny

horse, and a two-headed turtle. The others are stuffed or pickled in jars.

A Chicago native, Jim started out in a circus at eighteen. “As soon

as they handed me my diploma, I didn’t look back,” he says. “My dad

thought it was just a phase, and I wouldn’t stay with it.” His first job on

a tent crew paid fifty dollars a week. Over the years he took on dozens

of other positions. He drove trucks, did electrical work, shoveled ani-

mal poop. Along the road he learned acts from performers. He can walk

on broken glass, swallow fire, lay on a bed of nails, and pound some up

his nose.

In typical showman fashion, Jim bluffed his way into the Big Top.

That’s how he ended up working with elephants, some of the most dan-

gerous of circus animals. He handled them for nine years, coaching

them to stair-stack one another around a ring, bow on one knee, and

other things trainers make them do to appear tamed. Jim says the per-

formance is but a small part of the responsibility. “It’s a 24-7 job. You

always have to be available to take care of them. You clean up after

them. You wash them. You start to smell like them because it gets into

your skin. I had a waitress one time ask me if I was a pig farmer.”

Then he had to deal with animal-rights activists. “You get these peo-

ple telling you that you are being cruel and questioning your integrity

proof

all the time. You start to question it yourself. I miss the elephants, but

I don’t miss the elephant business,” Jim says.

Jim’s on the road about nine months a year. He winters in Tampa

and houses his live animals near Ocala. But you won’t catch his show

in Florida, not after what happened at the state fair in Tampa in 2005.

“I was on the bally and I see these deputies coming running up with

their guns drawn!”

I repeat what he said to make sure I heard him correctly. “Yes, they

had their guns drawn. I do not exaggerate.”

The deputies told him it was against the law to display his two-nose

cow, dwarf goat, and tiny horse—the farm animals. It so happens that

adi

Florida, a state where people can take their orangutan to Hooters, is

ro

the only one in America that explicitly prohibits the display of live de-

lF

formed livestock. They have to be dead—pickled or stuffed.

egn

The law dates back to 1921 and has rarely been enforced. Jim and the

irF

Florida State Fair operators didn’t know about it, and neither did the

Hillsborough County sheriff deputies, until a Tampa radio show host

412

complained about Jim’s sideshow.

Jim Zajicek, owner of Big Circus Sideshow. Photo by Lori Ballard.

The law passed at the same time as one banning human freak shows.

No one knew about that one either until after sideshows were well es-

tablished in Gibsonton. Jim says his friend Ward helped get the human

one overturned.

proof

Freak animal sideshow operators are a rarity, and Jim doesn’t have

the money to legally challenge the law by himself. Plus, there’s the

Florida Cattleman’s Association to contend with. The organization

squelched attempts to overturn the law, arguing that people might

purposefully breed animals to have deformities, you know, because

people are itching to build herds of six-legged goats and two-headed

cows to exhibit for three dollars a ticket.

“It’s just ridiculous,” Jim says with disgust. “Ward can tell you more

naM

about it and what they went through.” Once again, the yellow brick

Wo

road leads back to Ward. Is there anything he hasn’t done in regard to

hs

sideshows?

tsa

The next week I make the promised call to Ward. He quickly answers,

l s

sounding chipper and alert. He’s waiting.

’nWotW

The World of Ward

ohs

I miss his street off the Tamiami Trail and turn at the next to get a taste

51

of the neighborhood, which is only one in the loosest sense. The ’hood

2

doesn’t have sidewalks. It’s filled with old mobiles homes on sandy lots

with barely a sprig of grass. Yards, once parking areas for sideshow

trailers and carnival trucks, are filled with residents’ contractors vans,

semis, and old pickups. Children chase one another around a sagging

clothesline. A young man in a wife-beater bikes down a thin lane, steer-

ing with one hand and holding a can of Busch beer in the other.

By this standard, Ward’s corner is a palatial estate. His double-wide

sits on an expansive, green grassy corner lot secured by an 8-foot chain-

length fence. A crystal-blue swimming pool out front surrounded by a

low wall topped with small Grecian statues gives it a budget palazzo

feel. An added sunroom with aluminum windows stretches the width

of his mobile home. The side yard holds a shuffleboard court. I pull into

his looped green concrete drive and park beside an island of Greek col-

onnades, more statuary and Asian urns filled with dying plants. This is

Ward’s Ca’ d’Zan.

His sunroom door is open, welcoming me inside. The narrow room is

busy with drapes framing the wide windows, 1970s metal-framed patio

couches, 1960s lamps and a foot-wide Asian-patterned molding along

the ceiling, the kind you might see in a Chinese restaurant. It’s impec-

cably neat with shiny clean ashtrays and a fresh pack of matches on

every end table. There’s no smell of stale cigarette smoke or must, just

proof

stagnant air that’s sticky hot. The only solid wall is covered in posters

of newspaper clippings, photos, letters, and playbills protected behind

thin plastic—Ward’s wall of wonders.

With one knock, he pops out the front door wearing a tan guayabera

shirt, gray polyester slacks, and black-and-white saddle shoes, the kind