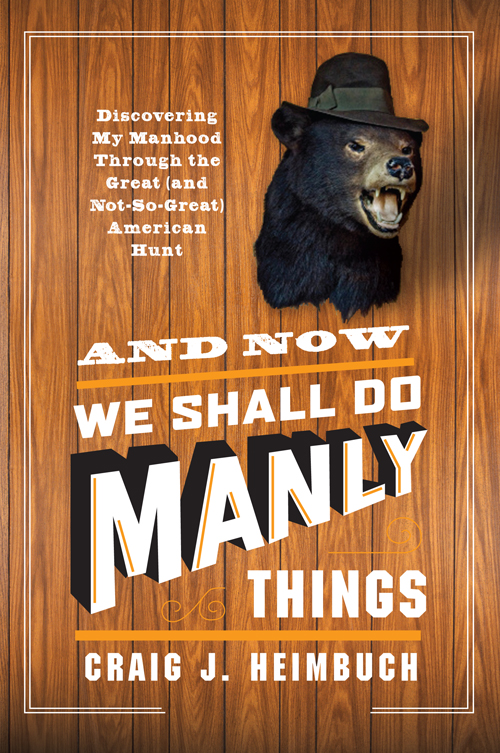

And Now We Shall Do Manly Things

Read And Now We Shall Do Manly Things Online

Authors: Craig Heimbuch

For Rebecca, the love of my life

Contents

W

e were just finishing packing up the car to head back to our place in Cincinnati when Dad asked me to go downstairs with him.

When I was young and my dad would call me down into his workshop, it usually meant trouble. Maybe my grades had been less stellar than I had led him to believe. Or maybe I had stretched the truth a bit about completing my chores. Either way, a trip into the workshop with Dad seldom resulted in warm, fuzzy father-son bondingâmore likely it was a disappointed glare and a good long talking-to.

But that was then. Now that I'm married and have three children, visits to the workshop usually involve a woodworking project with the kids or the never-ending retrieval of my college belongings that have been stored there for more than a decadeâyou never know when that freshman term paper on Chaucer might come in handy during a job interview.

I followed Dad down the stairs past the stuffed northern pike and the bearskin mounted on the wall. I've never been comfortable with the bear. The fish is one thing. I grew up fishing, and while I may have chosen a different pose than the curled-and-about-to-strike one opted for by the taxidermist, I recognize Dad's pride in that particular fish. There's also a tasteful piece of driftwood. I like that very much.

The bear, on the other hand, gives me the creeps. It's all soft fur, claws, and teeth. And the eyesâI swear it's looking at me, pleading with me to be taken down from the wall of the dim basement. “Put me in a ski lodge,” it's saying to me. “I want bikini models lying on me. I want to be the set of a late-night Cinemax movie. Please!”

“Dad,” I said, “we have to get going. I don't want to get home too late. What do you need?”

“I want to give you something,” he said.

“What?”

“Just something.”

Fine, I thought, let Dad be mysterious. Since my dad doesn't often veer toward the sentimental, I figured it was something practical. A coupon for Home Depot, perhaps, or an extra set of hex wrenches.

Instead, Dad reached into the rafters and pulled down the keys to the gun safe, which was mounted on a wall in the back corner of the workshop. He unlocked it without a word and pulled out a twelve-gauge Winchester over-under shotgun and handed it to me without much fanfare or flourish.

“What's this?” I asked rather dimly.

“It's a twelve-gauge Winchester over-under shotgun,” Dad said.

“Yes, but what is it for?” I asked.

“For shooting.”

Dad has always had a way with words.

“No,” I said as I tried to clarify, “why are you giving it to me?”

“I just thought you might appreciate it,” he said.

I must admit, it was a beautiful gun. The deep-brown wood, the dark-gray barrels and brushed silver-colored parts. I liked the way it felt in my handsâits heft and size, the particular angularity of the grip and stock.

I have a certain familiarity with guns. I understand their basic workings, having grown up in a gun-loving extended family, and can appreciate a beautiful gun when I see one. But don't confuse familiarity with comfort. Although I have fired more guns than most of my suburban peers, I have never fully immersed myself in the shooting and hunting culture of my family. My dad is a hunter. He's killed deer and bear and all sorts of birds. But even his bounty pales in comparison to that of his brothers. My uncles are the kinds of guys who spend rainy Saturday mornings watching worn VHS tapes of Alaskan hunting adventures (one in particular involving the downing of a wolverine seems to be the favorite). They spend their vacations hunting, plan for their trips all year long, and have passed their enthusiasm on to their own sons, my cousins.

This moment, however, marks the first time in my life Dad has made an overt gesture to welcome me into the fold. That I didn't ask for a gun, and am entirely too old to be receiving my first one, doesn't seem to have factored into his thinking. It's as if my dad just woke up that morning and decided it was time for me to be armed. I imagined him standing over the sink, a fresh cup of black coffeeâhe only ever drinks it black and told me that I'd better learn to do the same as you never know when someone might be out of creamâin hand, and with a manly stretch groaning, “I'm going to give Craig a gun today. Yup, that's what I'm going to do.”

My dad is not a man who prides himself on his possessions. He always taught us that doing was better than having, that a man is measured by the sum total of his experiences not his net worth. He does not have a large collectionâeight guns totalâbut this is the only one I remember him buying. He showed it to me right after he bought it, holding it up in front of him, examining it under the bare bulb hanging from the workshop ceiling like a museum curator holding an ancient relic.

I always assumed it was his favorite. He's used it maybe twice, so giving it to me was beyond generous; it was confounding.

“Dad,” I said, “don't take this the wrong way, but you aren't dying, are you?”

“No,” he said with a chuckle.

“You sure? No cancer? Heart disease? Diabetes?”

“Nope,” he said. “I'm fine.”

“Because if you've had a myocardial infarction, you can tell me,” I said. “Or if you're going blind . . .”

This went on for ten whole minutesâme running through every debilitating disease and condition I could think of only to be reassured time and again that he was in perfect health and that everything was in order. No, he and Mom did not have a suicide pact and, to the best of his knowledge, there was no mob contract out on either him or me.

I remained incredulous.

“You're just coming to an age,” he finally said, “when you might get interested in these kinds of things, and I wanted you to have this.”

I'd never owned a gunânever even had the thought of owning one. Sure, I've enjoyed shooting at soda cans and paper targets in my uncle's yard, both as a kid and as an adult. But shooting was a vacation thing for me, something I did while visiting my relatives in Iowa. Sort of like people from Kansas who spend their holidays skiing in Coloradoâit's an activity so tied to a specific place in my mind as to not be considered anywhere else.

So the idea of having a gun was completely foreign. I didn't have the slightest idea of what to do with it. I was excited (who isn't when receiving an unexpected gift?), but I also had some trepidation. Where would I keep it? It's not as if I had bought a gun safe in anticipation of the day when I might randomly be given a shotgun. It was as if he had just handed me the keys to a bulldozer. It was great and exciting, but using it would require an adjustment to my day-to-day life.

Not dwelling on the why of the situation any longer, Dad launched into a lengthy list of howsâhow to take the gun apart and put it back together, how to clean it and maintain it, how to store the ammunition and how to use the trigger guards. He covered so much ground so quickly, I should have been taking notes.

“This is how it comes apart,” he said, flipping a recessed switch forward and breaking the gun into three pieces. “And this is how it goes together.” With a couple quick snaps it was whole again.

“Got it?”

“Um,” I said, “can you show me one more time? You know, I just want to be sure I really got it.”

Again, a flick of the switch and the gun was in three pieces. This time he handed the pieces to me and I fumbled with them for a while before he grabbed the pieces and snapped them together as if by rote. Twice more he demonstrated, and with each successive flick and snap my confidence waned.

It was a master's class in firearms taught over the span of five minutes. I couldn't recall my father giving me so much detailed instruction and insight in such a dense burst before. I mean, Dad was always there if you needed help with homework or your taxes, but he wasn't the kind to give instruction or unprompted life lessons. As a teenager, the only advice I got about sex was an admonishment to not die of a venereal disease.

So Dad's effusive instruction on how to care for and handle this gun, while wildly out of character, was also oddly touching. I felt like he really cared. This was the father-son moment I had always been suspicious of in those movies of the week, and yet, here it was, happening right before me. Okay, so, at thirty-two, it wasn't exactly a scene from

The Wonder Years,

but I'll take what I can get.

I asked him to cover one more time the necessary implements to clean the weapon and demonstrated that, finally, I could indeed take it apart and put it back together. He gave me a case, geometric and sturdy with shiny metal sides and two hefty locksâI was tempted to handcuff it to my armâand a hundred rounds of ammunition.

He gave me one last bit of instruction, or perhaps it was more admonition before closing the safe and leading me back upstairs. “You better be careful,” he said, “and not fuck this gun up.”

A random gift, thorough instruction, and an unwarranted use of profanity? I began thinking of other medical conditions. Something was definitely out of the ordinary.

Mom must have known what Dad was doing, because when I came back upstairs, she gave me a big, excited hug, the same kind she gave me when my wife surprised me with a thirtieth birthday party. Mom and Dad said their good-byes to my wife and kids, and I went out to put my new gun in the carâalong with the portable crib for our daughter and our sons' stuffed animals.

We pulled away, and I gave a second look back over my shoulder at my parents waving from the front porch. I believe Dad was smiling a little larger than usual.

“What was that all about?” my wife asked before we reached the end of the block.

“Um.” I hesitated. “He gave me a shotgun.”

“What?!”

“Yeah, he gave me his favorite shotgun.”

“But you're not a gun guy. Why did he do that?”

“Because he wanted to.”

“Well,” she asked, “what's it for?”

I paused a second to consider the complicated answer. Should I tell her about family legacy? About fathers and sons? About his hopes that one day I would follow in his sporting footsteps? Should I tell her that I had no idea what prompted this generosity?

In the end, I gave the only answer I knew would not come across as dreamy or fanciful. I told herâ

“For shooting.”