Fringe Florida: Travels Among Mud Boggers, Furries, Ufologists, Nudists, and Other Lovers of Unconventional Lifestyles (15 page)

Authors: Lynn Waddell

Tags: #History, #Social Science, #United States, #State & Local, #South (AL; AR; FL; GA; KY; LA; MS; NC; SC; TN; VA; WV), #Cultural, #Anthropology

one another over who has rights to wear a location name. “People have

gotten killed over the bottom rocker,” Jim says in reference to a biker

shootout in a Nevada casino that started because a club wore its colors

in what another considered their territory.

Around the time Lace formed, 1%ers weren’t keen on women riding

their own bikes, Jim says. Most women in the outlaw biker world wore

patches that said they were property of a club member. “I don’t think

all 1%ers are chauvinists now,” Jim says, “but at one point it was pretty

much if you weren’t a white male, you could forget about it.”

proof

So, when Lace sisters became a three-patch club, it caused quite

a stir in the 1%er world. The fact that the club was Jenn’s, a woman

whom outlaw bikers knew through her late husband, Bear, Jim says,

probably made it worse.

Jenn says that 1%ers let her know they weren’t happy about it. “They

said, ‘Wait a minute. Do you know what you are doing, little girl?’” Jenn

played girly back, albeit with nerves of steel. She told them, “It looks

better. It’s a fashion statement, and you know I’m all about fashion.’”

Out of respect for the men’s clubs, Jenn says, Lace didn’t put chap-

ter locations on its bottom rocker. Rather the patch simply says, “Sis-

terhood.” She doesn’t see that as much of a concession given that Lace

ad

sisters are scattered and many are nomads, meaning they don’t have

ir

local or state chapters.

olF

The issue of patches is still touchy, as it is for any MC that dares to

eg

wear three. It makes traveling as a club particularly onerous, as 1%er

nir

protocol demands they notify every ruling club along their route that

F

they will be passing through.

47

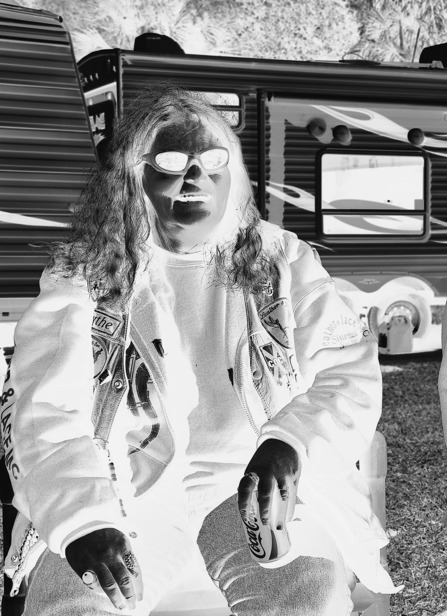

Leather & Lace mem-

ber Blythe Joslin, the

club’s web designer

and national board

member. Photo by

author.

proof

The territorial rule might seem arcane and the implied threat, melo-

dramatic, especially when you consider that Lace focuses on raising

money for breast cancer and teaching its kids how to run a popcorn

business. Lace sisters found out how maniacal 1%ers are about that

control when they took a road trip outside of Florida.

Lace sister Gail recalls the incident over Kahlua pudding shots. Due

to a miscommunication, she and other sisters found themselves in

lee

a bar with 1%ers who didn’t know Lace would be in their town. “We

ts

were only in the bar for a few minutes when these guys came in and

Fo

closed the doors. They wanted to know what we were doing there,” says

sr

Gail, who isn’t someone you’d expect to down beers with outlaw bik-

ets

ers. She’s working on a doctorate degree in emotional intelligence and

is

owns a horse-supply business in Stanfordville, New York. She’s careful

57

to phrase her reaction to the incident, as if 1%ers might take offense to

her depiction. “It was kind of interesting. We were in their territory.”

Outlaw Nation

Florida is a two-wheel state. One in twenty-five residents sports a bike,

making it second only to California in motorcycle saturation. Weather,

naturally, plays a big role in the state’s popularity with bikers. Florida

riders don’t have to worry about getting caught in snowstorms and

can ride year-round. Legally, they don’t even have to wear helmets, or

“brain buckets,” as many bikers call them.

Florida also has hundreds of miles of coastal highways offering

views of light sandy beaches and rolling turquoise seas. Inland, well,

much of inland Florida is rural with long, flat two-lane roads stringing

together small towns with mom-and-pop grills and hole-in-the-wall

bars welcoming bikers.

Florida’s large tourism engine also lures bikers with festivals

throughout the year. In addition to Bike Week, the biggies are Biketo-

berfest and the Leesburg Bikefest, which draws a quarter million bik-

ers. Even the carnie community of Gibsonton throws a biker extrava-

ganza complete with high-wire acts, which don’t involve motorcycles.

proof

Florida is flooded with motorcycle organizations and club chapters.

Recovering drug addicts, policemen, firemen, war veterans, lesbians,

Christians, nudists, Scientologists—every subculture you can think

of has an organized motorcycle club. On any given weekend there’s a

biker poker run going on somewhere in Florida.

Real estate being second only to tourism in Florida, developers

happily cater to the lucrative biker market. One planned motorcycle

community in central Florida advertises “Live Where You Ride” and

offers customizable garages for motorcycles. Its motto: “We’re building

freedom.”

But Florida isn’t just a big motorcycling state. It’s a gun-toting 1%er

ad

nation.

ir

One-percenter bikers have laid claim to Florida since the end of

olF

World War II. When the largest 1%er clubs later divvied up national

eg

territory, the Hell’s Angels got California, the Banditos got Texas, and

nir

the Outlaws MC scored Florida. “Everything else in the country was

F

kind of open for everybody else,” says Jim, the intelligence investiga-

67

tor. “That makes Florida a very significant state.”

The FBI, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF),

and local law enforcement agencies have entire units devoted to infil-

trating and tracking the moves of 1%ers in Florida. They estimate that

hundreds of 1%ers and their affiliates call Florida home. “It’s constantly

evolving,” says Jim, who works closely with the FBI. “Someone asks me

who’s fighting who, and I have to ask what day it is.”

Although each chapter of the Outlaws MC may have only a couple

dozen members, Jim says they still dominate the growing number of

smaller 1%er clubs. Swallowing prejudice, in recent years Florida clubs

have formed alliances with younger, minority clubs that ride Japanese

street bikes, commonly referred to as crotch rockets. This is a signifi-

cant change, he says, given that 1%er clubs for the most part are exclu-

sively white and have a reputation of bigotry. “Colors are everything to

these guys,” Jim says. “But in the long run, the color that matters most

is green.”

Every few years, the feds and local cops swoop in like the winds of

a hurricane and carry a posse of Florida’s 1%ers to jail on charges of

everything from drug trafficking to gunrunning. In the years between

raids, they attempt to infiltrate club ranks or surveil them like com-

mandos, sometimes from just across the street.

At Bike Week 2010 they are more overt.

proof

In the twilight of dawn, a huge RV emblazoned with “Daytona Beach

Police Department” rolls into an older sketchy neighborhood and parks

across the street from the Outlaws MC clubhouse. Dozens of members

from around the nation are bunking inside a dingy white house sur-

rounded by a chain-link fence.

About a dozen cops gather at the mobile command post for brief-

ings. The bikers send their lawyer over with hot doughnuts. The cops

respond by issuing tickets to bikes parked illegally on the sidewalk.

Throughout the day, the show of intense machismo escalates. Tat-

tooed bikers with potbellies, beards that could hide food for weeks, and

vests patched with the Outlaws’ trademark skull and crossed pistons

lee

sit on the front porch glaring across the street. Uniformed police glare

ts

back.

Fo

“We just want to send them a message,” Police Chief Mike Chitwood

sr

tells the

Daytona

Beach

News-Journal

. “We’ll be holding our briefings

ets

there for Districts 1 and 2, and the command post will be there for an

is

indefinite period of time.”

7

Indefinite becomes one day. Several neighbors complain to local

7

television and newspaper reporters—not about the bikers, but the

cops.

One neighbor tells Orlando’s WOFL-TV news that the Outlaws

cleaned up the neighborhood. “There was prostitution, crime, broken

car windows . . . These guys are the best thing that ever happened to

this town.”

The mobile command center pulls out the next afternoon.

Motorcycle Mayhem with American Express® Cachet

Farther south on A1A, Lace sisters are busy doing chores. Jenn runs a

tight household. With more than fifty people consuming every square

inch of her home and lawn for a week, no one except officers gets the

luxury of slacking.

“I have yard duty,” says an eighteen-year-old who came along with

her mother in hopes of getting a Florida tan. Upon arrival all members,

except the officers, had to sign up for a housekeeping job—either cook-

ing or cleaning the yard, house, or bathrooms.

Between chores, bike safety and CPR classes, investment club meet-

ings, shopping, media interviews, and nighttime parties around camp-

fires, some of the sisters get talked into leading newbies up the beach

proof

to see the mad scene in Daytona Beach.

Bike Week is of little interest to the longtime club members these

days. Jenn holds nationals during Bike Week so that members’ male

companions, the club’s “Big Brothers,” have something to do.

Bike Week veterans grumble when I mention Main Street. “We’ve

taken a few new sisters up there to see it because you need to see it

once. But we hate going. Once you’ve done it, you don’t need to see it

again.”

They complain the event has become overly commercialized and

overrun with posers and weekend warriors. That wasn’t always the

case. The genesis goes back to 1937 when daredevils raced on the hard-

ad

packed sands of Daytona Beach, the guttural sound of their motorcy-

ir

cles choking out the hollow roar of the Atlantic surf. The tide dictated

olF

start times, and most racers were semi-pro at best. They sped 80 mph

eg

around a primitive 3.2-mile track that stretched 1.5 miles north along

nir

the flat, tan beach before banking between the dunes to finish down

F

a narrow, raggedly paved stretch of Atlantic Avenue. Onlookers lined

87

the unfenced course, often getting sprayed with sand from the passing

full-throttle Harley-Davidson, Norton, and Indian motorcycles.

The Daytona 200, then coined the Handlebar Derby, became the

premier motorcycle race in America. Riders set speed records. News

photographs of bikers racing along the crashing waves sent a romantic

image of motorcycling on Daytona Beach around the world—freedom

and thrills in paradise.

When the annual race was put on hold during World War II due to

the rationing of fuel, tires, and metal, something funny happened. The

bikers continued to come. They cruised into Daytona Beach for four

days every March, riding on the sand, checking out other bikes, and of

course, partying until they couldn’t stand. Bike Week was born.

After the war, the races returned, drawing increasingly rambunc-

tious crowds and national media attention. In 1948

Life

magazine re-

ported that “for four days last month the resort city of Daytona Beach

could hardly have been noisier—or in more danger—if it had been un-

der bombardment.” The magazine went on to note that the American

Motorcycle Association was considering policing future races: “One

duty will be to restrain sophomoric cyclists who amused themselves

this year by tossing firecrackers into the crowd.”

Racing aficionados still consider the Daytona 200 the most grueling

proof

motorcycle race in America even though it’s been held on asphalt at the

Daytona International Speedway since 1961. The partying in bars and

on the beach long ago eclipsed the race in popularity. The majority of

motorcyclists who come to Bike Week these days don’t even go to the

race.

Bike Week’s geography changed, too. Due to Daytona Beach resi-