Freezing People is (Not) Easy (5 page)

Read Freezing People is (Not) Easy Online

Authors: Bob Nelson,Kenneth Bly,PhD Sally Magaña

My father's death flattened my mother's spirit for a long time afterwards. I was devastated but unsurprised. I grew up knowing my father wouldn't die in a bed. He was such a powerful manâbut also a powerful force of nature. So many of the choices in my life had been either in support or in defiance of him. When he died, I felt strangely freed from his path and knew that my own journey was now finally about to begin.

In later years I witnessed the enormous love affair people have with the Mafia from the popularity of numerous Hollywood productions, including

The Godfather

and

The Sopranos.

Since I grew up in a Mafia family, I knew gangsters were only lowlife killers, no different from and no more glamorous than the drive-by gangbangers and terrorists who indiscriminately killed young men, women, and children for standing on the wrong street corner or wearing the wrong colors. For me, human lives were sacred. I valued our existence and wanted to do everything I could to preserve and prolong precious life.

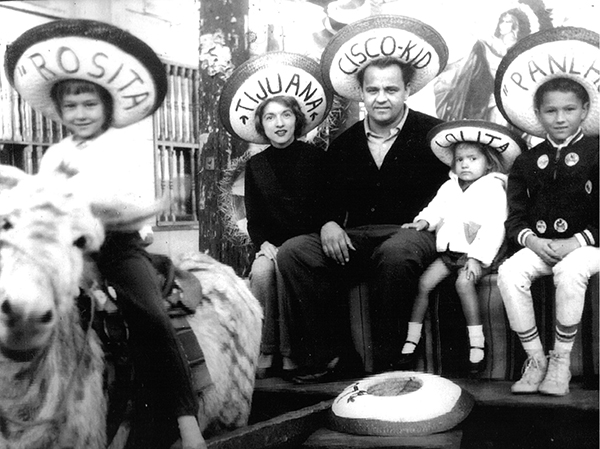

In 1962, soon after moving to California, Bob took his young family on vacation to Tijuana, Mexico.

Chapter 2

My Moment of Transformation

Ten years later, Elaine and I were still married

and still fighting. She still had a nasty mouth. I still had a penchant for leaving, and I still kept coming back because of her radiant spirit and our three adorable childrenâJohn, Lori, and our little Susan. During that time, we had switched coasts and moved to Los Angeles, where I settled into my career as a TV repairman. In our arguments, I admitted she was right about a few things: I was preoccupied with astronomy and obsessed with starting my own business. Ever since I was a little kid, forced into subservience by Grandma Witch and Big John, I had hated the idea of working for anyone else.

Those disagreements had led to our extended separation in the summer of 1965, which led me on a collision course with Professor Ettinger's

The Prospect of Immortality.

I had moved in with my friend Richard. His mother, Stella, was a wealthy and brilliant attorney, and she hoped I could keep Richard from drifting back to his heroin addiction. On the day I transferred my clothes to his plush apartment, I saw a birthday girl cutting her cake beside the swimming pool. She bewitched me with her hypnotic gaze and warm smile, looking yummier than the cake and reminding me of the legendary actress Ingrid Bergman.

The next morning I awoke from a peaceful sleep to the loud thud of a cannonball body hitting the water and a crescendo of laughter and screaming. I felt guilty, thinking my wife probably was not having a peaceful day with our small children. I peeked out and spied the birthday girl standing at the pool's edge. Every speck of her ravishing body not hidden by her lavender bikini evoked feminine tenderness; her breasts were the perfect size and slope, reminding me of a spectacular ski jump.

I quickly jumped into my swim trunks and proceeded out the door to join in the cannonball express. Three girls were at the far end of the pool. Instead of a thunderous entrance, I slipped in quietly and swam underwater toward the six tanned female legs.

When I arrived at the legs, I popped my head up out of the water, “Excuse me, girls, do any of you know Bob Nelson?”

With my sudden appearance, they looked at one another bewildered, shaking their heads. One finally said, “No, we don't know him.”

I then asked, with a cheeky grin, “Would you like to meet him?”

I noticed the apartment manager, Angie, calling and waving for me to come over, gesturing to her newspaper. She had flirted with me before and was probably just jealous, so I ignored her since I was feeling some heady potential in the pool.

Even my Ingrid Bergman beckoned me. “Come on, Bob, and play cannonball with us.”

But Angie insisted, “Come here, Bob; this is important.” Her hand waved hurry,

hurry!

I made an accounting of my dilemma: six eager eyes, three happy mouths, and six supple breasts versus Angie's hand holding a decidedly

unimportant

newspaper. My choice was clear, though. I reluctantly climbed out of the pool and splattered over to the concrete steps to see why she needed me so damned terribly much.

Angie looked up, her eyes coquettish. “Have you ever heard of freezing people a moment before their death and then many years later returning them back to life?”

I stared in disbelief at her words as the ground seemed to shift beneath me. My imagination stretched to its absolute mind-boggling limit.

“What kind of nonsense is this, science fiction?” I blurted.

Angie seemed exasperated with me. “No, this is for real. A Michigan physics professor has written a book titled

The Prospect of Immortality.

”

I grabbed her newspaper, slowly reading the article about Professor Robert Ettinger to soak up every precious word from those scant paragraphsâto force that knowledge into my brain, even by osmosis. I was shocked, and the three lovelies in the pool were completely forgotten.

Was it possible that death could be altered by this procedure? Could we really freeze peopleâand sometime in the distant future, wake them up?

I don't remember leaving the building or asking permission to take Angie's newspaper, but somehow I wound up in my car rereading the article again and again. I was entranced. That night I couldn't sleep and couldn't stop fantasizing that cryonics would change life and death on our planet. I felt transported, just as when I had heard in 1957 that the Soviets had launched

Sputnik

into orbit. Traveling to other worlds was now possible, adding decades to one's life was now possible, and seeing civilization hundreds of years after being born was now possible. That concept of limitless possibility left me dizzy.

The idea was at once preposterous and yet completely logical. But I couldn't make an evaluation about cryonics based on the filtered and simplified version written by a journalist. I needed to go to the source and read Professor Ettinger's book.

A week earlier I had signed a huge contract with a company called Nadel to repair all the damaged electronics they had bought and shipped from anywhere in the United States. It was quite an opportunity for me, and I was scheduled to start that next morning. But I was thinking of bigger issues than switches, wires, and transformers. I could only focus on the transformative power of the technology hinted at by that newspaper article.

I stopped by several bookstores on the way to my first sales meeting, but no one had yet received Professor Ettinger's book from the publisher. Finally, in the Yellow Pages I found a bookstore in Santa Monica that had just gotten the book, their shipment still unpacked.

I hated postponing such a good business opportunity, but I called Nadel and rescheduled our first sales meeting. I raced to the store to pick up the book and offered to pay them double, even triple, for a copy. I offered to help unpack, tempted to get on my knees and plead for this book. The guy at the counter thought I was a nutcase, so he went into the stockroom and returned several minutes later with a single copy of

The Prospect of Immortality.

Grabbing it from his hand, I began reading before reaching my car. I was enraptured from the first line in the preface written by legendary cryobiologist Professor Gene Rostand: “We are at last forced to concede the real possibility that the means for freezing and resuscitating human beings will one day be perfected, at however distant a time this may be.”

What a strange choice of words. “We are at last forced to concede . . .”

I drove down Sunset Boulevard to the beach, gleaning more tidbits of precious information at each stoplight. I grabbed a blanket from my Porsche, looked for an isolated spot in the sand, and settled down to devour the book; spellbound, I lost all track of time. I read as the sun ascended far overhead, as the high tide forced me to scoot back a few feet, and until the dying twilight rendered further reading impossible. I closed the cover and stared at the book. It had crisp pages and a sharp binding in the morning; now it looked worn.

It is difficult to describe my reaction to Professor Ettinger's bookâso much potential, so much hope was contained between the covers of this astounding book. For the first time in my life, I could see a bright light at the end of the tunnel of my existence, and the warmth of this light was very comforting indeed.

I envisioned governments and billionaires from around the world clamoring to fund cryonics suspension research. Professor Ettinger would be deluged with grants to support this life-giving science. I looked out at the Pacific Ocean and could almost visualize on the horizon a spaceship from another galaxy, gifting us mortals with information that would save billions of research dollars and centuries of researchâcatapulting our world eons ahead with scientific knowledge.

I was convinced that what Ettinger proposed would be done immediately. I foresaw the Soviets, who had challenged us to a race to the moon, challenging us to a new raceâto break the “biological ice barrier.” Cryonics intersected my love of astronomy, as I understood that suspended animation would be a necessary ingredient for long-term space travel. It would allow people to stay dormant for months, even years, without overwhelming life support requirements. When they arrived at their distant planet, they could then be revived. With cryonics, we could travel to far-away solar systems and galaxies. Professor Ettinger's book was embellished with stardust, and that stardust had forever touched me.

My mind was inexorably bent toward cryonics and this new way of looking at death. For if a person can be revived, then he had never actually died. This is probably the most misunderstood aspect of cryonics suspension. Once a person is dead, he is dead. Nothing can bring a dead body back to life. But death does not happen in an instant; we travel a long journey to the land beyond the veil. Along that path, we pass through a complicated biological sequence as blood stops flowing, chemical reactions halt, electrical impulses stop, and there is no life force to prevent the decay. By lowering the body temperature at an early stage of the dying process (that is, clinical death), we slow down the journey and stop the dying progression, thereby keeping the patient from ever reaching the stage of complete irretrievable death. Freeze the person and stop the dying.

Cold slows down the biological clock; the colder the environment, the slower the clock. So at liquid nitrogen temperatures (-320°F; for comparison, 200 proof alcohol freezes at -173°F), time practically ceases to exist. These slowed chemical reactions are governed by the third law of thermodynamics. And through the years, I've discovered that people's responses to cryonics are governed by Newton's third law of motion: For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. As much as I love the potential and hope provided by cryonics, there are people who equally loathe the concept that cryonics can ever be a reality.

By altering our concept of deathâthat dying might be postponed hundreds of yearsâcryonics circumvents centuries of religious faith and beliefs that have been embraced for millennia. But life has a precedent of breaking such traditions of human behavior. This change is the natural order of life; it keeps happening again and again. And the privilege of witnessing such evolution and revolution is one of the primary and primal reasons I love being alive and why I want to stay alive for as long as I possibly can.

Sitting in the sand with a pink-and-orange sky before me, I wondered if I might be mentally unbalanced in this immediate and overwhelming fascination with the potential created by freezing people. I couldn't rationalize how obsessed I had become with this book while everyone else seemed more concerned with the price of gasoline.

To test my judgment, I returned to the Santa Monica bookstore a week later and purchased three more copies of Professor Ettinger's book, and then I pondered the people in my life that I considered to be the most intelligent and open-minded. The first was the Duke family, with whom I had lived as a renter for about three years.

The next person was my roommate's mother and a brilliant attorney, Stella Gramer.

The last victim was Paul Porcasi, who was an official with the Mensa society, an organization requiring members to have an IQ in the top 2 percent of the population.

I asked them to read

The Prospect of Immortality

and give me their opinion. Three for three, they agreed with me and found it logical and reasonably presented. Stella, in her late seventies, was prepared to sign up at once for her own suspension. She reasoned that if the procedure didn't work, she would simply remain dead. Paul agreed to help establish a legal organization to support freezing research and to publish a newsletter to educate the public about this fascinating new science.

Backed by their support, I felt assured I was thinking sensibly. The next couple of months were spent in an intellectual stasis, anxiously waiting to find someone that knew more about cryonics, and I was undeterred by the seeming indifference of the rest of the world.

I wasn't the saucer chaser or the self-taught pseudo-scientist. I needed some proof of concept. Even though I was young, with many years of life still before me, I knew that no one would emerge from suspended animation within my lifetime. Sure we could freeze people and leave them in liquid nitrogen indefinitely, but I needed some assurance, something more than faith, that reanimation truly did lie at the other end of the cryonics tunnel.