Freezing People is (Not) Easy (10 page)

Read Freezing People is (Not) Easy Online

Authors: Bob Nelson,Kenneth Bly,PhD Sally Magaña

I was bluffing. Cryonics was controversial, and a good outcome wasn't guaranteed, regardless of Helen's wishes. Besides, once Helen was declared clinically dead, any legal delay would be devastating to a successful perfusion.

Fortunately, Maryann backed down; she didn't want a fight any more than I did.

I quickly began preparations for Helen's perfusion at the moment she was declared dead. I told the hospital staff that the CSC was a cryobiological research organization, Helen was a medical donor, and she needed to be covered in ice so that we could accept her donation. To my relief, they cooperated. When Joseph Klockgether arrived at the hospital to retrieve Helen's body, she was already packed in ice and waiting at the loading dock.

Joseph brought her to his mortuary and performed the perfusion. He then placed Helen in the temporary storage container with Marie Sweet and covered her with dry ice. The entire process from death to temporary storage took about seven hours. Thanks to the cooperation from the hospital and Joe's swift action, Helen Kline was frozen under the best conditions.

I thought of a movie I had seen recently,

Planet of the Apes.

While Charlton Heston was portraying a suspended NASA astronaut hurtling toward a distant planet, mimicking what we hoped to accomplish, I was busy freezing Helen Kline and struggling to make this science-fiction notion into reality.

The CSC members unanimously agreed that we should try to give Helen a chance at long-term suspension. We had our second frozen hero, but we had yet to take on our first paying patient.

When remembering the early history of cryonics, it is impossible to ignore this frail little woman. While in the final stages of lung cancer, Helen overcame her pain and suffering and found the strength to organize the first California cryonics meeting. I am forever indebted to her.

I met Russ Stanley at that first meeting of California cryonicists in Helen's home. He was a tall, slender older-looking gentleman with an obnoxious Cheshire cat grin, but quite athletic. He swam laps in his aboveground pool every day, even on the coldest winter morning.

Every day for the next two years, he called and talked to me for hours if I couldn't find a way to escape. It seemed he ate, drank, and slept cryonics. If there was anything about cryonics going on, anywhere in the country, he knew about it.

He had accumulated every newsletter and article ever published on cryonics, enough to stuff a full-size file cabinet. His genuine enthusiasm was infectious, and he often provided great little pearls of new information.

On September 6, 1968, I was in San Francisco organizing a new cryonics society. During the meeting, Paul Porcasi, the CSC secretary, phoned me that Russ had suffered a heart attack and been taken to the Santa Fe Medical Center in Los Angeles, where he had been pronounced dead.

The hospital staff ignored the documentation Russ carried on him, which gave specific instructions to cool his body with ice at the moment of his death and to contact the CSC immediately. Instead they contacted Rosario, a man I had met at Russ's house, who was listed as next of kin. Rosario thought cryonics was ridiculous, but he respected Russ's wishes and fulfilled them the best he could.

Paul was a nervous wreck. The hospital refused to cool Russ's body without consent from the attending physicianâan infuriating stance, because brain damage began shortly after death. Rapid cooling slowed the deterioration and, in theory, preserved the memory of the patient. I adored Russ and wanted to give him the best chance for a full recovery.

I used my most authoritative tone, hoping to spur him into action: “Paul, contact Joseph Klockgether and ask him to meet you at the hospital. The hospital needs to release his body to Joseph. Also, bring along all Russ's donation papersâthey're on file in my office.”

“Should I also bring the CSC's articles of incorporation?” he asked.

I felt powerless so far from Los Angeles. I replied, “Bring them, but don't go flashing them around.”

Hospitals at that time were skittish of freezing bodies for later reanimation, but they were receptive to anatomical donations for medical research. If he approached the staff as a research organization, he had a better chance of receiving their assistance.

They finally cooperated. Joseph took possession of Russ's body, covered him with ice, and brought him to the mortuary. After the perfusion, his body was placed alongside Marie Sweet and Helen Kline. A total of six hours had elapsed between the time of Russ's death and the start of his perfusion. Like Marie's perfusion, the intervening time made this an imperfect operation. If Russ ever opened his eyes, he would likely have memory loss, but his suspension was still considered viable.

The day I returned from San Francisco, I contacted Rosario Coco. Russ had made Rosario executor of his estate, and I was anxious to learn the financial arrangements for his suspension. I knew Russ had impeccable records and documentation; no individual was more prepared for cryonic suspension. However, there was still the enormously important matter of financial arrangements.

Russ had told me he had a substantial bank balance. Although it didn't cost more to keep him in temporary storage with Marie and Helen, we couldn't sustain them foreverâwe desperately needed funding for a permanent storage facility. Russ knew our needs, knew our limitations, and surely had left sufficient funds to finally accomplish the task.

Russ had described Rosario as his “sweetheart from way back.” That was no real surprise to meâI had suspected Russ was gay when he introduced me to Rosario at the first meeting. To me the man looked like an owl. Rosario had big rings around his eyes and a tiny beak of a nose. He was small, with wavy gray hair and a curt personality. I knew that Russ had trusted this man and thought the world of him.

In his will, Russ bequeathed ten thousand dollars to the CSC, payable in two five-thousand-dollar installments. I was stunned, as I had anticipated at least double that amount to accomplish Russ's suspension and perpetual storage. I delicately grilled his friend about the funds to pay for Russ's suspension. He brusquely retorted, “That's all I know.”

Obviously Rosario wanted to dismiss us, but he was executor, and I wasn't going to make it easy for him. I asked, “Was this a donation to the CSC, or were we expected to freeze and store him perpetually for that amount?”

He said, “I have no idea,” then abruptly ended the conversation with “Good-bye.”

I stared at the telephone receiver until my backside begged me to get out of the stiff wooden office chair. Once again I found myself in the peculiar position of placing another patient in temporary storage when I knew the CSC couldn't provide perpetual maintenance. Russ's total purpose in his later life, at least during the years I knew him, was supporting the research of cryonics science. I was surprised to learn that one of the most fanatical and wealthy cryonics advocates had left only ten thousand dollars for his suspension. I knew Rosario was an honest manâRuss must've underestimated the necessary funds. I would have to invest the money he did provide wisely. It had to stretch a long way.

Chapter 6

The Vault

CSC's membership had grown to nearly one hundred.

Anticipating a deluge of cryonics requests, we set up a for-profit corporation to design, develop, and provide cryogenic hardware equipment for CSC's future needs. Marshall Neel was the president of this company, Cryonic Interment, since he had been our business brain. He was a refreshing counterweight that kept meâthe passionate, optimistic dreamerâgrounded. I loved his objectivity and realism; he'd often say “Change wives, change problems.”

Our plan was to have CSC contract with CI to perform perfusions and store suspended members. Despite our current meager funds, we felt assured about the future of cryonics. With that optimism and Russ Stanley's donation, we wanted a permanent storage facility.

Finding and setting up the proposed facility was far more difficult than I had imagined. Since the law limited storage of bodies at a mortuary to less than six months, the city of Buena Park wanted Marie, Helen, and Russ out of the Rennaker Mortuary. The health department had extended the deadline for us several times but was getting impatient. Joseph Klockgether had pleaded with me, “Build your vault, Bob, and get your people out of here.” If we couldn't store bodies at Joseph's mortuary, how could we get past regulations for storing them at our own facility?

The answer turned out to be surprisingly simple and practical. We could build an underground vault in a cemetery. There we would be immune from the local laws of legal disposition of our frozen patients. I also had to face the grim possibility of failure, since the technology was still experimental. With the patients already in a cemetery, they would be considered legally interred. Should the cryonics program dissolve, they could remain in the vault unless family members decided otherwise.

It sounded so uncomplicated, but finding a willing cemetery wasn't easy. Joseph used his contacts, but the answer we kept hearing was “No, there's no precedent for such interments.”

Of course I knew the real reason for the rejections. Cemetery directors didn't mind dealing with dead peopleâjust as long as they stayed dead. Future reanimation was all too new and strange for them to accept. After months of abysmal luck, a beam of Southern California sun finally permeated through.

My mother-in-law had recently purchased two plots at the Oakwood Memorial Park Cemetery in Chatsworth, a suburb of Los Angeles. It was a beautiful place with rolling hills, surrounded by picturesque mountainsâan ideal place to be dead, I suppose. I found their number in the Yellow Pages and called the office. I explained that CSC was a nonprofit cryobiological research organization and that we were looking for a place to store medical remains for research. I received an appointment to see the owner, Frank Enderle, immediately.

He was a cordial gentleman and listened politely. As soon as I mentioned cryonics, he leaned back in his chair and knew exactly what I wanted. To my surprise, he told me he would think about it. His brother was on the California State Cemetery Board, and he wanted his brother's legal advice before making a decision.

Frank wasn't bothered by the idea of hosting a cryonics facility as long as the cemetery had no liability. Once he received the go-ahead from his brother, he responded to me, insisting that the underground facility be constructed using the rigorous mausoleum code.

On my third visit, Frank drove me through the cemetery to choose a location. Just two hundred feet beyond the main offices, I found the perfect spot. The ground was level and situated close to the road, making it easily accessible to liquid-nitrogen delivery trucks. I didn't really expect Frank to agree, but he once again surprised me, and I successfully obtained that location.

Although Frank was not interested in cryonics, he was intrigued by its novelty. While I wrote out the check for the large plot, his general manager, a tall lanky man named Chuck, walked into the office.

Frank asked him, “Do you have any objections to having the cryonics vault on cemetery grounds?”

My heart was in my mouth; I feared he might say something to obstruct us.

A thoughtful look flashed across Chuck's face. “I do have one concern. How many frozen people could be in that vault?”

I put on my most trustworthy, concerned expression and answered, “At the very mostâtwenty.”

After a long pause, he looked me straight in the eye. “What are you going to do if they wake up and start fucking and fighting down there?”

My serious face broke into a huge grin. It was good to know that they had a sense of humor. They certainly needed it in later years.

I contracted a company to build the vault. It was constructed of steel rebar and cement, much like a swimming pool, with interior dimensions of twelve by eighteen feet. A door was built into the steel roof, which slid horizontally on rollers. A ladder led from the door at grass level to the bottom. Meanwhile, we had to find a capsule for our frozen heroes to rest in long-term suspensionâbut the capsules weren't cheap.

At this point, between the plot of land and the construction of the still-unfinished vault, CSC had spent close to seven thousand dollars of Russ's ten-thousand-dollar donation.

We lucked into finding a tank that could hold thirty patients at an industrial liquidation yard in Los Angeles. Only slight modifications were necessary, since it had all the instrumentation to monitor the core temperature and liquid nitrogen boil-off.

The top of the massive capsule had a sealed lid, which allowed access to the patients. The five-thousand-dollar price tag was a bargain; the original purchase invoice showed the capsule had cost nearly $150,000. There were, however, some serious downsides. First, the capsule was too large to fit in the plot we had already purchased, and we didn't have the money to build a new, larger vault. Second, we'd need a lot of liquid nitrogen to fill its cavernous interior, as well as the money to maintain it. Marshall and I figured five or six paying suspensions would finance the capsule, but we had an immediate need for our current cases.

In the end we banked on our optimism and took a leap of faith with the big capsule. CSC had around twenty-five-hundred dollars left in its bank account, and I arranged for a loan to pay the rest. Frank allowed us to store the capsule in the cemetery's heavy-equipment yard until we found it a permanent home and Cryonic Interment could begin using it. We were excited about the future. Soon we would have the paying suspensions to operate our new, state-of-the-art facility.

I was selling cryonics and our new facility to the public, traveling the country, giving presentations, and talking about CSC's new capabilities. After interviews on several national television and radio talk shows, I was flying high and feeling golden. A guy like me from my background, on radio and television, was seen as an expert?

Bob Nelson during a radio interview in Los Angeles

My wife was amused by the media attention but embarrassed by its bizarreness. She focused on the children and tried filling the void created by my long hours away from home. The kids enjoyed seeing their dad interviewed on TV at first, but it soon became mundane. One time I sat down to watch the replay of an interview with

Channel 5 News;

however, my daughter Lori was already watching a program and didn't care to switch the channel to see her dad.

I always felt confident that with all the exposure, we were just one phone call, one more TV appearance, one interview, just one more day away from financial solvency. I hated feeling so focused on cash though. I had such big goalsâwe were fighting for the future of humanityâand yet here I was in this position of going after the money.

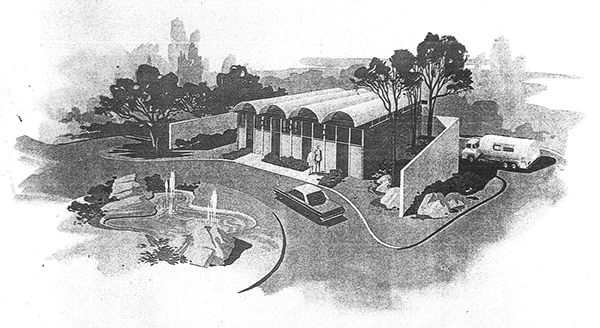

Robert Prehoda and Dr. Brunol still came to dinners and gave talks, but since there was no money, they just gradually faded away. In our newsletter we boasted of the world's first cryotoriumâa proclamation I later regretted, because my detractors claimed I had overstated our accomplishments. But we were desperate for paying suspensions, and I thought a little exaggeration was justified. Hundreds of letters and phone calls were pouring into CSC, and people were signing up. Still, there were no new patients, and the expenses just continued to mount. I didn't know how much longer I could hang on, but I couldn't think about failure. Somehow, I hoped we could save our frozen heroes.

Artist conception of future CSC cryonics facility

In late 1968 we encountered another turn of fortune. Louis Nisco had been in cryonic suspension at Cryo-Care Equipment Corporation in Phoenix, Arizona, for a year. His daughter, Marie Brown, was desperate. She could no longer afford the monthly storage and liquid-nitrogen maintenance payments, and Ed Hope, who owned the company, was threatening to terminate the suspension. Marie had purchased her father's capsule from Ed for forty-eight hundred dollars. She still owed fifteen hundred dollars and was making monthly payments along with storage and liquid nitrogen fees. She couldn't keep up with the payments and wanted my help. I called Ed Hope to get his side of the story. Ed was a businessman, pure and simple. His main line of work was manufacturing wigs, but when he saw an opportunity to make money, he added on the business of cryonics capsules.

Ed and I appeared together once on the

Louis Lomax

television show. That was during the summer of 1966, and it was my first-ever TV appearance. The producer of the show asked if I could bring a visual demonstration. I told him I had just returned from a visit to Ed's Cryo-Care facility in Phoenix and would ask him if he could bring a capsule to the show. I didn't need to ask Ed twice. The

Louis Lomax

show was nationally syndicated, and it meant big-time sales potential to Ed. He showed up at my house two days before the show, pulling a trailer with

Cryo-Care

and

Human Suspended Animation Equipment

plastered all over it. My wife was mortified about what the neighbors thought.

Three minutes before the show, Ed was still in his dressing room. I went in and asked what was keeping him. He was frantic. He couldn't find his toupee and refused to go onstage without it. At that moment Lomax grabbed me and said we had only one minute leftâforget about Ed. He got me onto the soundstage just in time. I was a nervous wreck; it felt like I had eaten a cotton ball sandwich for lunch. Lomax introduced me to the live audience as “the guy who could get you frozen and bring you back.” My secretary told me afterwards that I looked like someone desperately in need of a bathroom. I managed to parrot some of the things I'd heard Professor Ettinger say about cryonics, and our forty-five-minute segment stretched to an hour and fifteen minutes. An audience member asked if people should wear something warm for their suspension, which loosened me up. Eventually Ed came out, wig neatly arranged on his melon, and demonstrated his capsule. He managed to mention his phone number, just in case someone wanted to buy one.

Ed Hope was ruthless; if he couldn't make a buck, then he wouldn't waste his time. When I asked him about Marie's situation, he told me, “If that capsule isn't out of here in two weeks, I'm going to kick the fucking thing into the street. Is there any part of that you don't understand?”

I understood all rightâEd meant exactly what he said. I called Marie, and she was badly shaken and needed an immediate resolution. I saw an opportunity: I badly needed a capsule, since the big one couldn't be used yet, and she needed someone to store her father at a price she could afford. I offered to pay the remaining balance she owed on the capsule and to take charge of her father's suspension. In return, I asked that she donate her father and the capsule to CSC and continue making payments of $150 per month to cover the costs of storage and liquid nitrogen. I told her of our plans to eventually get our large capsule ready and that we would transfer her father to the capsule at that time. She gratefully accepted.

I mentioned there might be some shuffling of bodies before we got our large capsule functioning, but I didn't provide specifics. In truth, I wanted to open her father's capsule and place Marie Sweet, Helen Kline, and Russ Stanley in there with him. I wasn't completely honest with her, but I figured that since she was donating the capsule to CSC, we could do what we wantedâand we had a real need. I reasoned that if they were reanimated, it would be more fun to be part of a group of survivors rather than be a lonely, solitary product of an experiment. Nevertheless, of all my dealings in cryonics, this omission bothered my conscience the most.