Framingham Legends & Lore (14 page)

Read Framingham Legends & Lore Online

Authors: James L. Parr

H

ARMONY

G

ROVE

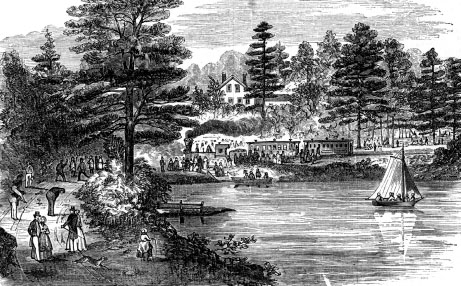

While manufacturing and commerce clearly benefited from the coming of the railroad in 1835, the rail connections also helped turn Framingham into a recreational destination for people across New England. Harmony Grove, one of the first family parks in the country, was opened on the eastern shore of Farm Pond in 1846. Owner Edwin Eames laid out walking paths on the four-acre site and built a boathouse, a dance pavilion and a one-thousand-seat outdoor amphitheatre. Eventually the park would cover fifteen acres. A branch of the Boston and Worcester Railroad ran right through the grounds, and it became a popular destination for boating, fishing, picnics and games. The amphitheatre was frequently used for large civic gatherings, including all sorts of civic, religious and reform organizations. The most significant of these was the annual rally of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, held there from the Grove's opening in 1846 until 1865.

Antislavery was by no means a universally popular cause, even in Massachusetts, where slavery had been prohibited since 1783. Many thought abolitionists were unnecessarily stirring up trouble, or that slavery was unfortunate but it was up to the individual states to decide, or that there were simply many more pressing issues of greater importance. There was also, no doubt, plenty of racism. Yet, for the most part, Framingham proved a tolerant venue for the abolitionists.

An 1852 view of Harmony Grove, from

Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion

.

The Framingham Anti-Slavery Society was founded on the day after Christmas 1837 at a meeting in the vestry of the Hollis Evangelical Society (later Plymouth Church) at the Centre. Its first president was Ebenezer Stone, with other officers including Ezra Hemenway, Edmund Capen, Charles Parkhurst, William P. Temple (uncle of Josiah, the historian), Joel Tayntor, Dana Bullard, Lawson Rice and Perisan H. Vose. The one hiccup occurred when the Middlesex County Anti-Slavery Society tried to hold a meeting on October 16, 1853, at the Framingham Town Hall (still standing on the Centre Common, now called the Village Hall). Although they had arranged to use the hall in advance, the selectmen had gotten cold feet, decided not to unlock the building and made themselves scarce. Dr. Henry O. Stone tracked down the chairman of the selectmen, who agreed that the group should be allowed to meet and found the caretaker to let them in. Meanwhile, the meeting had commenced outdoors on the common.

The Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society's annual rally on July 4, 1854, was an event of national significance. The speakers constituted almost a “who's who” of the abolitionist causeâWendell Phillips, Sojourner Truth, Henry David Thoreau, Lucy Stone and Stephen S. Foster. But it was William Lloyd Garrison, whose Boston newspaper

The Liberator

had been dedicated to promoting abolitionism for over twenty years, who made the biggest headlines.

The country was in turmoil over the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act a month earlier, which sought to eliminate the national debate over slavery by leaving the matter up to the individual states, but instead inflamed both sides. Particularly hated was the Fugitive Slave Act, which allowed escaped slaves to be arrested in free states and returned to their masters in the South. Garrison declared his belief in the words of the Declaration of Independence that all men were created equal and then burned a copy of the fugitive slave law, along with a judicial decision enforcing it, because they contradicted this sentiment. When he went on to condemn the United States Constitution as “a covenant with death and an agreement with hell,” and burned it as well, he went further than even many of those in attendance were willing to go. His actions sparked both condemnation and praise across the nation and were one more step toward driving a deep fissure through the heart of the nation over slavery.

L

UCKY

L

OTHROP

W

IGHT

The Confederate attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861 thrust America into the Civil War. Thousands of volunteers from across the nation enthusiastically enlisted in the cause, including over five hundred from Framingham. One of those volunteers was a young man named Lothrop Wight. Son of a prominent real estate owner in town and Framingham Academy graduate, the twenty-three-year-old Wight mustered in as a second lieutenant with the Sixteenth Massachusetts Volunteers in July 1861. After a short trip to Boston, the regiment traveled on to Fort Monroe, Virginia, for training. Within a short time, Wight found himself battling not for his country, but for his career as a soldier.

During the course of training at Fort Monroe, Lieutenant Wight had become unhappy with the leadership of his captain, Henry Lawson, and had filed charges against him. Confident that Lawson would be found guilty and removed of his regimental command, Wight began voicing that opinion to the soldiers serving under him. Over the course of several days in October, the lieutenant was heard to have called Captain Lawson a “damned fool.” He also remarked that if the regiment were to go into battle, Lawson would be relegated to the rear of the company and he, Lieutenant Wight, would be called upon to lead the troops. A sergeant in the company looking for extra blankets was told by Wight to take Captain Lawson's, because “he wouldn't be needing them much longer.” Not surprisingly, the arrogant and downright insubordinate words of Lieutenant Wight caused charges to be filed against

him

, and soon he was on trial under general court-martial for, among other infractions, “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman.” Several of Wight's men testified against him, and he was promptly found guilty of all charges and “cashiered out,” or dishonorably discharged, in November 1861. The charges against Captain Lawson were not pursued, and he continued to serve in the Sixteenth Massachusetts Volunteers until he died of disease at Chancellorsville, Virginia, in October 1864.

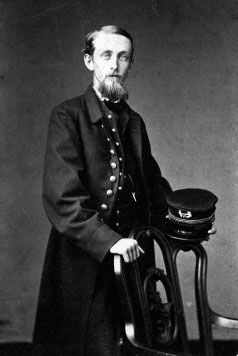

Lothrop Wight.

Lothrop Wight was given another chance to prove that he could be a good commander. He enlisted in the U.S. Navy in June 1862 and served with distinction on several ships for the duration of the war. Wight's various positions of command on the ships

Wachusett, Vanderbilt

and

Mendota

included officer of the watch, acting master's mate and acting chief. While serving on the

Vanderbilt

, he crossed the oceans of the world hunting down the Confederate ship

Alabama

, with no luck. The crew of the

Vanderbilt

did, however, capture three blockade runners during its yearlong chase.

It was while serving on the USS

Mendota

, however, that Wight proved himself in battle and earned a place in Framingham legend. The

Mendota

had been patrolling the James River throughout 1864, supporting the Union attack on the Confederate-held city of Richmond, Virginia, and was regularly assaulted by artillery on the shore. In one particularly intense attack at the end of July, Wight was hit by a Confederate bullet. Miraculously, the bullet struck a penny that Wight was carrying in his pocket. The bullet made a large indentation in the penny, fusing its silver metal to the copper of the coin and saving the life of the lucky lieutenant. After the war, Wight became a florist in Wellesley Hills, where he lived quietly until his death in 1918. The lucky penny that saved his life was passed down to his granddaughter, who donated it to the Framingham Historical Society and Museum in 1976.

The penny that saved the life of Lieutenant Wight.

Framingham boasts another Civil War sailor with a strange tale; yet this sailor did not fight under the Stars and Stripes, but under the flag of the Confederacy.

A R

EBEL ON

U

NION

A

VENUE

By the time he arrived in Framingham from Post Mills, Vermont, in 1898, Thomas Chubb had already lived a life of adventure and achievement. Shortly after his birth in Charlestown, Massachusetts, in 1839, Chubb and his family moved to Galveston, Texas, where his father, also named Thomas, began a successful shipping company. At the outbreak of the Civil War, the Yankee-born Chubb men served the Confederacy proudly. The elder Thomas captained a blockade runner, the

Royal Yacht

. Thomas the younger was a commander on several different ships and was eventually captured near the end of the war. He obtained his freedom by paying a substantial fine.

After the war, Chubb contracted yellow fever and was advised by doctors that his health would only improve if he moved northâback to the area of his birth and the home of the victorious Union army. He arrived with his family in Post Mills, Vermont, in 1868 and, not surprisingly, got a chilly reception from the local citizens. Chubb soon became fast friends and business partners with local entrepreneur William Marsten. Together in the early 1870s they founded a successful fishing rod manufacturing company. The Chubb factory produced the first machine-made rods in the world, which were renowned and coveted for their superior quality. Chubb's rods and other fishing products were promoted heavily, the distinct star logo and Chubb's bearded visage appearing in hundreds of newspaper and magazine ads across the country. Eventually the people of Chubb's adopted home came to accept and even respect him, so much so that he successfully ran for several local offices before being elected to both the Vermont house and senate.

By 1898, the successful sailor, businessman and politician needed a change. His fishing rod factory had burned and been rebuilt several times. Although it was still successful, Chubb sold out and moved south to Framingham, where he bought a house on Union Avenue. He later built a house on Warren Avenue and became active in town affairs. Every summer he would return to Post Mills to spend time with his Vermont acquaintances. In the summer of 1910, Chubb was gathered with friends, saying his usual goodbyes before his trip north. Before departing, he startled his friends by revealing a strange premonition he had. He told them that he would not be returning to Framingham; that he would die in Post Mills and be buried next to his wife on the ninth of July. Chubb was so sure of his premonition that he packed his most treasured possessionâa Confederate flag. Within a few days of departing Framingham, Thomas Chubb's prediction had come true. He was laid to rest in Vermont on the very day he had predicted, his head resting on the Confederate flag under which he had fought so many years earlier.