Framingham Legends & Lore (9 page)

Read Framingham Legends & Lore Online

Authors: James L. Parr

There were 153 Framingham men who responded to the Lexington alarmâabout 10 percent of the entire population of the town, an impressive number constituting about half the number of men above the age of sixteen, many of whom would have been too old or otherwise infirm for military service. Many on the list of those who served that day bear the names of families we have already discussedâtwo Clayes, two Nurses, two Buckminsters, two Havens, three Browns, three Winches, four Hows, four Rices, five Stones, nine Eamesesâbut also on the list is the singular name of Peter Salem, a private in Captain Edgell's company.

P

ETER

S

ALEM

, F

ORMER

S

LAVE AND

M

ARKSMAN

Peter Salem, also sometimes called Salem Middlesex, was born a slave to Jeremiah Belknap of Framingham. He was admitted as a member of the church in 1760. Shortly before the Revolutionary War, he had been sold to Major Lawson Buckminster, son of Colonel Joseph and grandson of the first Joseph Buckminster. After his service as a Minuteman during the Lexington alarm, he enlisted in the regular army less than a week later and continued to serve in varying stints for much of the rest of the war. (Since slaves could not enlist, Buckminster must have already given him his freedom in order to serve in the army.)

He spent much of the war as body servant to Colonel Thomas Nixon. According to most accounts, it was Salem's shot that fatally wounded the British commander Major John Pitcairn at the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775. (He is also thought to be the African American figure depicted in the lower right-hand corner of John Trumball's famous painting of the battle.) He served with distinction until the end of the war and was present at the Battle of Saratoga, Valley Forge, the Battle of Monmouth, as well as other engagements. In 1783, he returned to Framingham, married Katy Benson and built a house to the east of Sucker Pond, near the present-day intersection of Fairbanks Road and Route 30. He removed to Leicester, Massachusetts, about 1793. He never found much success as a farmer, but earned a living as a basket weaver and caning the seats of chairs. By all accounts, he was a much-liked member of the community and often told tales of his service alongside Colonel Nixon in the war.

Peter Salem monument in the Old Burying Ground.

When the aged Salem was no longer able to earn enough to support himself, the town of Leicester sent him back to Framingham. As the latter was his native town, it was deemed responsible for caring for him under the poor laws of the period. Tradition records that Salem's contributions were not forgotten and Framingham welcomed him home. He died in 1816, aged about sixty-five years, and his remains were interred at the Old Burying Ground on Main Street. Many decades after his death, the town erected a monument on the site to preserve the memory of its African American Patriot.

T

HE

N

IXON

F

AMILY IN

W

AR AND

P

EACE

Colonel Thomas Nixon, who was Peter Salem's commanding officer, was one of three Nixons to serve in the Revolutionary War. The most prominent was General John Nixon, Thomas's older brother.

General John Nixon was born at Framingham on March 1, 1727, shortly after his father Christopher had moved there from parts unknown and married Mary Seaver of Sudbury. John first enlisted in the army at the age of eighteen, serving in the expedition that captured Louisburg from the French in 1745. He served extensively in the French and Indian War, participating in many campaigns between 1755 and 1762, and retired as a captain. In 1757, he bought land on the north slope of Nobscot Mountain, just over the Sudbury line, but continued to attend church in Framingham and had all his children baptized there. He commanded a company of militia from Sudbury at the Battle of Lexington and Concord, and five days afterward he was commissioned a colonel. He commanded a regiment of three hundred men at the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775, and was severely wounded there and had to be carried from the field. By August, he had recovered sufficiently to be promoted to brigadier general, a rank he held for the remainder of the war. His first command was at Governor's Island in New York Harbor, but his brigade withdrew to the Hudson Valley after Washington's army was defeated at the Battle of Long Island in 1776. He saw his most extensive combat during the pivotal Saratoga campaign in 1777, where the rebel victory helped convince France to join the war. After the war, he resided briefly in Framingham before returning to Sudbury. He eventually removed to Middlebury, Vermont, where he died at the age of eighty-eight in 1815.

Colonel Thomas Nixon was born in Framingham on April 27, 1736, and married Bethiah Stearns, eventually inheriting her father Timothy's extensive estate on the northeast corner of the intersection of Edmands and Nixon Roads. This property in the northwest part of Framingham remained in the Nixon family for generations. He followed his brother into military service during the French and Indian War in 1755â59 and declined the command of a regiment of the Framingham militia in 1774, instead electing to serve under his brother in the Sudbury company. Similarly, he became a lieutenant colonel in his brother's regiment and then a regimental colonel in his brother's brigade. After the war, he returned to Framingham before dying on a voyage to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in 1800.

Thomas's son, Thomas Nixon Jr., was born on March 19, 1762, in Framingham. He enlisted as a fifer at the age of thirteen in Captain David Moore's Sudbury company and saw action at Lexington and Concord. (His recorder and pages of sheet music are in the collection of the Framingham Historical Society and Museum.) He served in the army from 1777 to 1780 and again from 1782 to 1783, having only reached the age of twenty at the war's end. After the war, he built a house that still stands on part of his father's estate and became a prominent member of the community in his own right, serving as captain of the militia as well as selectman. He died on January 4, 1842.

His son, Warren Nixon, born March 9, 1793, if anything, gained even greater standing in the town, serving as teacher, surveyor, selectman and justice of the peace. He was a talented draughtsman and drew the first truly comprehensive map of Framingham in 1832. At the time of his death in 1872, there was perhaps no more esteemed and distinguished resident. A few years prior, the town had presented him with an embossed Bible in recognition of his contributions to Framingham over the course of his long life. But his rough-and-tumble father, who had spent his teenage years as a fifer in Washington's army, had not been so impressed with Warren's bookishness. The following advertisement appeared in the

National Aegis

, a Worcester newspaper, on May 15, 1811:

NOTICE. The Subscriber will be very much obliged to any person who will give him any information relative to his Son WARREN NIXON, who left his home on the 21

st

of March last in a very unexpected and unaccountable manner. He has from his youth been exceedingly attached to literary pursuits, and it is believed, has, in some degree, injured his brain. He is about eighteen years of age, about five feet seven inches high, light complexion, with very full light blue eyes. His Father will be much rejoiced to see him return to his home, and will do every thing

[sic]

in his power to render him contented and happy. Those printers who will have the humanity to insert the above, will confer a favor on the disconsolate Parent. THOMAS NIXON

. Framingham.

That Warren did eventually return home and prospered perhaps should be a comfort to the disconsolate parents of teenagers everywhere.

J

OHN

A

DAMS

I

NSPECTS

G

ENERAL

K

NOX

'

S

A

RTILLERY

T

RAIN IN

F

RAMINGHAM

When George Washington took command of the Continental army in July 1775, it consisted almost entirely of Massachusetts and other New England men who had surrounded General Howe's British regulars in Boston since the Battle of Lexington and Concord. The British had expelled the Patriots from Breed's and Bunker Hills in Charlestown, but at a considerable loss of life. As the two sides settled down to a long siege, the British control of the seas meant that they could hold out in Boston indefinitely. Meanwhile, one of Washington's primary goals was to turn the collection of militiamen he had inherited into a proper army.

To that end, Washington appointed Henry Knoxâtwenty-five years old at the timeâas commander of the artillery, such as it was. Since artillery was the only thing that might drive the English out of Boston, it was important to amass whatever he could find. Knox immediately came up with the idea of transporting the large number of mortars and cannons that had been captured at Fort Ticonderoga when it had been seized by Ethan Allen's Green Mountain Boys in May 1775. The only problem was that Ticonderoga stood on the shores of Lake George in upstate New Yorkâthree hundred miles to the west, and on the other side of the Berkshire Mountains. Washington gave Knox the go-ahead and authorized an expenditure of £1,700 for the purpose.

Knox arrived at Ticonderoga in early December 1775 and immediately set about assembling the large number of oxen, wagons, sleds, sledges, etc. needed to transport the dozens of field pieces and ammunition. The journey was arduous and took much longer than the three weeks Knox had estimated. That Knox was able to do it at all given the terrain he encountered, using mid-eighteenth-century technology, was an engineering marvel.

According to General William Heath, Knox arrived at the army's headquarters in Cambridge on January 18, 1776, and the artillery train, at that point near Springfield, Massachusetts, was ordered to halt in Framingham. We know the artillery was at Framingham a week later. Patriot leaders John Adams and Elbridge Gerry were on their way to attend the Continental Congress in Philadelphia and stopped for dinner (a midday meal in this case) on January 25, 1776, at (where else?) Buckminster's tavern. Adams noted in his diary that afterward “Coll. Buckminsterâ¦shewed us, the Train of Artillery brought down from Ticonderoga, by Coll. Knox.” The two then proceeded to supper at “Maynards,” presumably the old Jonathan Maynard tavern on Maple Street, which by this time was operated by his son Joseph, although historian Stephen Herring suggests they may have gone to William Maynard's on Salem End Road just east of the junction with Temple Street, before heading to Worcester the next morning.

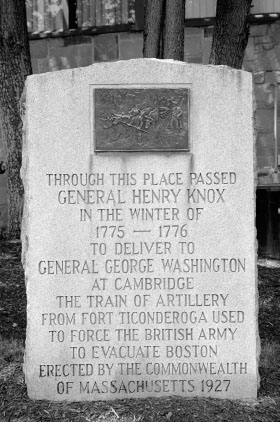

Monument memorializing the passage of the Knox artillery train through Framingham.

Photo by Edward P. Barry

.

It makes sense that the artillery would be held up in Framingham, a sufficient distance away from Boston, so as not to tip off the British before they were able to be deployed. The guns were kept at the houses along “Pike Row,” a line of properties that began at the Pike-Haven house (still standing) on the corner of Grove and Belknap Streets and extended eastward. The oxen were said to have been kept at the Hemenway (later Whiting) farm on Brook Street, in a barn that burned down in 1958. Just how long the artillery remained in Framingham is open to conjecture, although the first deployment in positions surrounding Boston did not begin until late February.

In the end, the cannons served their purpose: once the colonists had taken Dorchester Heights (in what would now be termed South Boston), they commanded Boston, and the British withdrew from the city on March 17, 1776.

L

OYALISTS IN

F

RAMINGHAM

Not everyone in Framingham supported the Revolution, of course. Although since Patriots dominated the town, as they did Massachusetts and New England in general, most of those who harbored doubts about the rebel cause largely kept those thoughts to themselves.

One Loyalist created a great many headaches for Colonel Joseph Buckminster, by then in his late seventies. Commodore Joshua Loring of Roxbury, who had commanded the British naval forces on Lake Champlain during the French and Indian War, left his home on April 19, 1775, never to return, as he could not bear the thought of abandoning the flag and king he fought for in his distinguished military career. His young son John Loring joined the Royal Navy at the age of fourteen but was soon captured by the rebels and imprisoned in the jail at Concord. His prominent uncle Obadiah Curtis interceded and, given the boy's youth, he was released into the care of Curtis's father-in-law, Colonel Buckminster in Framingham, sufficiently far from the sea to avoid getting into further trouble. That Buckminster was a Patriot was unquestioned; two of his sons were officers in the militia and fought at Bunker Hill, while his son-in-law Colonel Jonathan Brewer was an officer in the Continental army. Nonetheless, Buckminster soon found himself in an awkward position, caught between his sense of family obligation and the anger of his friends. Loring persisted in taunting Buckminster's Framingham neighbors, calling them “rascally rebels” and worse, and the enraged townsmen threatened to demolish Buckminster's home for harboring the young Tory. It was no doubt with a great sense of relief that Buckminster saw Loring leave town in 1776 as part of a prisoner exchange. John Loring went on to a distinguished career in the Royal Navy, attaining the rank of commodore and seeing extensive service during the Napoleonic Wars.