Foundation Game Design with ActionScript 3.0, Second Edition (43 page)

Read Foundation Game Design with ActionScript 3.0, Second Edition Online

Authors: Rex van der Spuy

An alternative way of casting variables is to use theaskeyword. You can write the previous line of code like this:

currentGuess = input.text as uint;

This line is very readable and the effect is exactly the same. It's entirely up to you which style of casting you prefer.

Now that you have a number in thecurrentGuessvariable, you can use the if/else statement to analyze it.

if (currentGuess > mysteryNumber)

{

output.text = "That's too high.";

}

else if (currentGuess < mysteryNumber)

{

output.text = "That's too low.";

}

else

{

output.text = "You got it!";

}

The logic behind this is really simple. If thecurrentGuessvariable is greater than themysteryNumber, “That's too high” displays in theoutputtext field. If it's less than themysteryNumber, “That's too low” displays. If it's neither too low nor too high, there's only one alternative left: the number is correct. Theoutputtext field displays “You got it!”

Not so hard at all, is it? If you understand how this works, you might be pleased to know that writing if/else statements will be at the very heart of the logic in your game design projects. It really doesn't get much more difficult than this.

The logic works well enough, but you can't actually win or lose the game. The game gives you an endless number of guesses and even after you guess the mystery number correctly, you can keep playing forever! Again, a fascinating glimpse into the nature of eternity and the fleeting and ephemeral nature of life on Earth, but not at all fun to play!

To limit the number of guesses, the program needs to know a little more about the status of the game and then what to do when the conditions for winning or losing the game have been reached. You'll solve this in two parts, beginning with displaying the game status.

To know whether the player has won or lost, the game first needs to know a few more things.

- How many guesses the player has remaining before the game finishes.

- How many guesses the player has made. This is actually optional information but interesting to implement so let's give it a whirl.

When a program needs more information about something, it usually means that you need to create more variables to capture and store that information. That's exactly what you'll do in this case: create two new variables calledguessesRemainingandguessesMade. You'll also create a third variable calledgameStatusthat will be used to display this new information in theoutputtext field.

- Add the following three new variables to the class definition, just below the other variables you added in previous steps:

public class NumberGuessingGame extends Sprite

{

//Create the text objectspublic var format:TextFormat = new TextFormat();

public var output:TextField = new TextField();

public var input:TextField = new TextField();

//Game variables

public var startMessage:String;

public var mysteryNumber:uint;

public var currentGuess:uint;

public var guessesRemaining:uint;

public var guessesMade:uint;

public var gameStatus:String; - Initialize these three new variables in the

startGamemethod, like so:public function startGame():void

{

//Initialize variables

startMessage = "I am thinking of a number between 0 and 99";

mysteryNumber = 50;

//Initialize text fields

output.text = startMessage

input.text = "";

guessesRemaining = 10;

guessesMade = 0;

gameStatus = "";

//Add an event listener for key presses

stage.addEventListener(KeyboardEvent.KEY_DOWN, keyPressHandler);

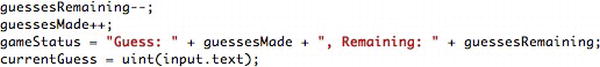

} - Add the following code in bold to the

playGamemethod:public function playGame():void

{

guessesRemaining--;

guessesMade++;

gameStatus

= "Guess: " + guessesMade + ", Remaining: " + guessesRemaining;

currentGuess = uint(input.text);

if (currentGuess > mysteryNumber)

{

output.text = "That's too high."

+ "\n" + gameStatus;

}

else if (currentGuess < mysteryNumber)

{

output.text = "That's too low."

+ "\n" + gameStatus;

}

else

{output.text = "You got it!";

}

} - Compile the program and play the game. The

outputtext field now tells you how many guesses you have remaining and how many you made.

Figure 4-16

shows an example of what your game might look like.

Figure 4-16.

The game keeps track of the number of guesses remaining and the number of guesses made.

Let's find out what this new code is doing.

The new code assigns the three new variables their initial values.

guessesRemaining = 10;

guessesMade = 0;

gameStatus = "";

The total number of guesses the player gets before the game ends is stored in theguessesRemainingvariable. You gave it an initial value of 10, but you can, of course, change it to make the game easier or harder to play. You also want to count the number of guesses the player makes, so aguessesMadevariable is created to store that information. When the game first starts, the player has obviously not made any guesses, so theguessesMadevariable is set to 0. ThegameStatusvariable is a String that will be used to output this new information, and you'll see how it does this in a moment. It contains no text initially (it is assigned a pair of empty quotation marks).

Now take a look at the first two new directives in theplayGamemethod.

guessesRemaining--;

guessesMade++;

When you play the game, you'll notice that Guesses Remaining in the output text field decreases by 1, and the Guesses Made increases by 1. That's all thanks to the two lines that use the extremely convenient

postfix operators

.

Remember the discussion of increment and decrement operators from the previous chapter? If you want to increase a value by 1, you can write some code that looks like this:

numberVariable += l;

It turns out that increasing values by 1 is something programmers want their programs to do all the time. So frequently, in fact, that AS3.0 has special shorthand for it: a double-plus sign, which is a special kind of operator called a postfix operator. You can use it to rewrite the previous line of code like this:

numberVariable++;

It will do exactly the same thing: add 1 to the value of the variable. You can use another postfix operator, the double-minus sign, to subtract 1 from the value of a variable in exactly the same way, like this:

numberVariable--;

Postfix operators change the value of the variable by 1 each time the directive runs. The directives in theplayGameevent handler are run each time the Enter key is pressed, which, of course, is each time the player makes a guess. Having theguessesRemainingandguessesMadevariables update with each key press is therefore a perfect way to keep track of the number of guesses the player has made.

When the game starts, theguessesRemainingvariable is initialized to 10. On the first click of the guess button, this directive is run:

guessesRemaining--;

It subtracts 1, making its new value 9. On the next click, the very same directive runs again, and 1 is subtracted for the second time, leaving it with a value of 8. One will be subtracted every time the Enter key is pressed for the rest of the game.

TheguessesMadevariable does the same thing, but instead uses the double-plus sign to add 1 to its value. When you test the game, you can clearly see how this is working by the way the values update in the output text field.

Let's create another new variable in the program calledgameStatus. You declared this variable as a String, which means that it will be used to store text. The first time it makes its appearance is in this directive:

gameStatus

= "Guess: " + guessesMade + ", Remaining: " + guessesRemaining;

(This is a very long line of code, so to allow it to print easily in this book, I've split it up over two lines by breaking it at the equal sign. In your program, you can probably keep it all together as a single unbroken line of code, as you can see in

Figure 4-17

.)

Figure 4-17.

Keep long bits of code together on a single line.

For the uninitiated, this is a potentially terrifying segment of code. What on earth does it do?

The first time you make a guess in the game, you'll see the following text on the second line of the output text field:

Guess:

1,

Remaining: 9

This text has to come from somewhere, and it's the preceding directive that's responsible for putting it all together.

Think about it carefully: what are the values of theguessesRemainingandguessesMadevariables the first time you click the Guess button? (They're 9 and l.)

Okay then, let's imagine that you replace the variable names you used in the directive with the actual numbers they represent: 9 and 1. It will look something like this:

gameStatus = "Guess: " + 1 +

",

Remaining: " + 9;

Make sense, right? Great, now let's pretend that the plus signs have disappeared and everything is inside a single set of quotes:

gameStatus = "Guess:

1,

Remaining: 9";

Aha! Can you see how it's all fitting together now? That's exactly the text that is displayed in the output text field.

Figure 4-18

shows how the entire line of text is interpreted, from the initial directive to being displayed in the output text field.

Figure 4-18.

From the kitchen to the plate: string concatenation in action!

The directive uses plus signs to join all the separate elements together to make a single cohesive string of text. This is something known in computer programming as

string concatenation

. This just means “joining text together with plus signs.” It's a very useful technique to use when you need to mix text that doesn't change with variables that do. Because the values of the variables change, the entire string of text updates itself accordingly. It's so simple, really, but a sort of magical thing to watch when the program runs.