Forty Rooms (15 page)

Authors: Olga Grushin

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary, #Contemporary Women, #Family Life

As she talked, she began to push the many-colored glasses of sundry shapes and sizes and the plates, no three alike, into incongruously mismatched islands amidst the cornucopia of gilded fruit, arranging them on embroidered placemats and silver chargers.

“When I opened the hatbox for the first time and saw what was inside, I was enchanted. There were postcards of castles and moonlit lakes and girls in elegant dresses. The pictures themselves were black-and-white, but the girls’ lips, cheeks, and parasols were

rouged red by hand. I had never seen anything like it, and it just took my breath away. But I was a secret hoarder. I didn’t want to squander my enjoyment on just any ordinary day, so I didn’t allow myself to look at anything properly, I just piled it all back into the hatbox, shut the lid, and hid it under my bed. For weeks afterward I went about, pretending nothing was there, all swollen with my secret. And every single day I was just dying to get the box out and pore over my treasure, to look at the beautiful girls, but I didn’t let myself. I thought I had plenty of time, so I would choose a perfect moment, make it a special occasion. My birthday, perhaps, or maybe New Year’s.”

She watched her mother in silence, without stopping her, without helping her. A chill was starting to creep up her spine. Her mother’s face had hardened into an unfamiliar expression of grim determination, and her movements as she darted about the table, sorting, shifting, rearranging, grew faster and faster.

“Then one day, when I was at school, my father’s new wife cleaned my room. She found a pile of old junk under the bed, and she threw it all out. So you see, I didn’t have any time, as it turned out. When you put something off to do later, it just doesn’t get done, not in the same way. Because there never is any time, there never is any later . . . There, all finished. Where do you keep your matches? I want to light these now.”

She stared from her mother to the table, groaning under its mad glittering, gleaming, sparkling weight, and back to her mother.

Her heart was beating slow and hard.

“Mama,” she said. “Has something happened?”

“Five minutes!” Paul trumpeted from the kitchen.

“We really should wake him up now,” her mother said.

Together they looked at the closed door of the bedroom. The candle flames bent left, bent right in an invisible breeze. The certainty of an imminent disaster hollowed out her insides. She said, “Something is wrong.”

“Yes.” Her mother stood still, her hands hanging loose by her sides, as though depleted all at once of her frenzied energy. “Don’t tell him I told you, not yet, I want tonight to be . . . to be like before. I promised him I wouldn’t tell you at all, and I didn’t, not before the wedding anyway, I didn’t want to ruin it for you. But it’s time now, I think. Papa is sick. Really sick. It’s cancer, and not the kind they can . . . That is, they don’t know how long . . . Well. All I wanted to tell you is, if you want Papa to see your children, you should start having them now.”

“And dinner is served!” Paul announced, carrying in a steaming tureen. “Wow, look at all that, it’s like the cave of Ali Baba! . . . Hey, shouldn’t you wake your dad now?”

“I’m awake, I’ve been awake,” her father said, entering the room. “I’ve just been resting a little.”

She heard him shuffling as he walked, but that was only because of Paul’s slippers, of course: they were much too big for him, weren’t they, and his own had been packed away already. She could not bring herself to look into his face at first. When she did, she saw what had escaped her in the fuss of the preceding days. He seemed much older than his sixty-eight years, and his skin had a grayish cast, and his eyelids were shadowed by exhaustion, and his mouth was thin and hard. Sorrow washed over her because

she knew that she would never again be able to recall his face from before, the way it had been, that he was somehow already lost to her—and then he noticed the outrageous, clashing abundance of the table and laughed, laughed in just that contagious way in which he used to laugh when she was a child, slapping his knee with his hand, his face starting into life with a myriad of wrinkles, his eyes dark with a disarming, childish mirth; and she went all quiet inside.

The four of them sat in the festive light of a dozen candles, amidst the pewter Thanksgiving pheasants and the bronze Christmas deer and the porcelain Easter rabbits and the glass grapes, and lifted mismatched champagne flutes in a toast to the new couple’s happiness. The bubbles fizzed on her tongue, tasting of innocence and loss.

“Please, may you pass salt,” said her mother to Paul, exhausting her English.

“Don’t offend now, but this Taj Mahal thing? Is ugly,” said her father, laughing again.

Why, she thought, why hadn’t they told her before the wedding? She would not have gone through with it but would have returned home instead, would have added no more days to the careless tally of years she had already missed in her father’s life. But it was too late now, and there was only one way left to hold at bay the numbing grief that was spreading through her like a slow, viscous spill.

Gods, my gods, sometimes the harder path is the opposite of what it seems.

15. Bedroom

Conversation in the Dark at the Age of Twenty-seven

“Are you asleep?”

“No. Well, maybe. I guess I am. Is something wrong?”

“I just can’t sleep. I’ve been lying here thinking.”

“About?”

“Not anything in particular. Just things. Did I ever tell you about this seminar I went to in my first month in America?”

“Yes. Possibly. No.”

“I don’t remember now what the subject was, but it was one of those workshops where everyone sat in a circle, and the professor had us write down our ‘strengths,’ what we were really good at, you know, on a piece of paper, and then we went around the circle, and everyone read what they’d written. It’s the usual stuff, right, everyone has done it dozens of time, in interviews, and class discussions, and church meetings, everyone here always talks about their strongest points, their weakest points, and the

answers are all a given—‘I’m creative,’ ‘I excel at multitasking,’ ‘I’m good with languages,’ ‘I’m a great team player.’ Except that I had never done it before, so I had no ready pat formulas in my head. I remember sitting there for the first minute, absolutely mortified, not having any idea what to say. Then I thought about it, I mean really thought about it, and wrote this long, earnest paragraph. I wrote that I believed I could sometimes sense the essence of things—houses, books, faces, moments in time—that I sometimes caught a whiff of their innermost souls, their unique smells, and that what I was hoping to do with my life was to render these impressions in words so vivid, so precise, that others could feel them too. Then the five minutes were up, and we started going around the circle, and all the long-haired boys said they were creative and all the foreign-exchange girls said they were good with languages. By the time my turn came—it was toward the end—I had caught on perfectly, so I too said I was good with languages. I remember feeling so relieved that I had not been the first one to give my answer . . . But I wonder now . . . It’s like life, you know: the more you learn what is expected of you, the more you fall into these patterns, these grooves, these ruts, the less unique your experiences become, the less unique you become yourself. If you didn’t know, for example, that people got married at a certain age and had children at a certain age and retired at a certain age, would you know to do any of those things, or would you do something else, something entirely different? Because it can’t all be pure biology. I mean, I know you pride yourself on believing only the things you can see, and I love that about you, it’s so reassuring, but—but don’t you have this

sense sometimes that our life is essentially just the tip of the iceberg, and if you stop clinging to your puny bit of ice in fear or out of habit and just dive into the water, you will discover this luminous mass going down, deep down, and meet creatures you can’t even imagine, and have thoughts and feelings no one has ever had before . . . That is really why I came here in the first place, and why I stayed here, you know. I mean, I told you I stayed because of that relationship I was in at the time, and that was part of it, I suppose, but mainly, I knew what was expected of me in Russia, and I thought that here I would be able to escape it, escape having a predictable life . . . Well, that, and the language, of course. Because languages are like that too, you know? When you are first learning a language, you are swimming in this glorious sea of possibilities—you feel that you are free to take all these little specks of meaning floating around you and combine them into the most fantastical, gorgeous, dreamlike structures that will be yours and no one else’s, amazing castles, cathedrals, entire cities of words rising out of chaos. But then you start learning the rules, the grammar, what goes with what, and then, worst of all, all these common expressions and mass-issued turns of phrase start impressing themselves onto your brain, so that when you say ‘time,’ you think ‘valuable’ and ‘waste of’ and ‘waits for no man,’ and when you say ‘love,’ you think ‘star-crossed’ and ‘blind,’ and when you say ‘death,’ you think ‘kiss of’ and ‘bored to’ and ‘dead as a doornail’—and before you know it, your words have become these prayer beads strung together and worn-out through countless repetitions, and what original meaning there was is completely obscured . . . Perhaps the longer you use the language,

the more in danger you are of becoming gray and trite and shallow, I thought, but if you learn a new language, you can start all over again. And I feel, I really do feel that there are these great big truths out there, or no, not truths, exactly, just these pure slabs of . . . of meaning, of feeling, these monumental things we contend with as humans—you know, love, death, beauty, God—and I thought, if I come to them clean and childlike and with my mind free of preconceptions, or else if I come to them using two roads at once, both the front door of my native language and the servant entrance of my adopted language—or is it the other way around, do you think?—in any case, maybe then I will actually stand a chance of stumbling upon some vast reservoir of poetry just waiting out there in the universe . . . Because I write poetry, you know. Whenever you see me scribbling and I tell you these are just thank-you notes or grocery lists, they aren’t really. Well, you’ve probably figured it out for yourself by now, but I wanted to tell you anyway. I wanted to tell you for a long time, but I was being . . . superstitious about it. I guess I felt I needed to keep my poems secret from everyone until I was ready to share them with the whole world. And I’m still not ready to do that, but I’ve been thinking about something my mother said right after our wedding, and, well . . . I just wanted to tell you. Because I feel happy, you know, happy about us, and the baby, of course, but I’m also scared about the baby, and so sad about Papa, and sometimes—and please don’t be upset now—but sometimes I feel a little lonely, too, so I just thought, if I told you . . . Hello? Hello? Oh, gods, I’m talking to myself again, aren’t I? Paul? Are you asleep?”

“What? No. Well, yes, I’m afraid I was. But I heard you

saying something about a seminar and that you were good at languages . . . Oh, and did you say you wanted to name our son Mustard, or did I dream that?”

“Yes, actually, Mustard is an old family name on my father’s side, so I think it would be nice . . . Ah, you should hear your silence right now. You dreamed that.”

“Phew, I was worried for a moment there. I think I can stay awake now. Sort of. Do you want to try saying it again? Whatever it was you were saying?”

“It was nothing, really. Just go back to sleep.”

“You should get some sleep too while you can. Only three more weeks

now.”

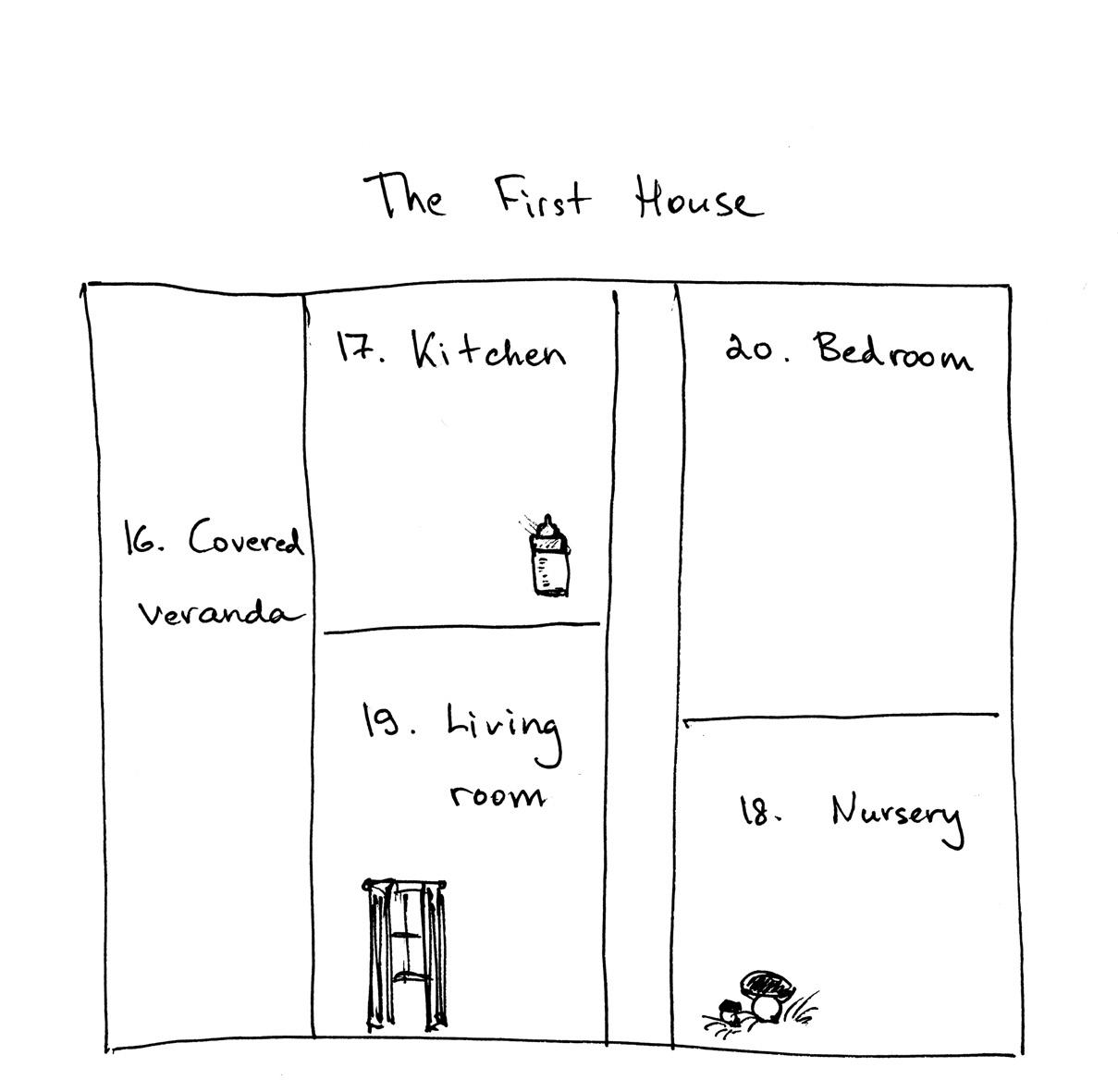

16. Covered Veranda

The Swing

When the screen door banged behind them and they entered the covered veranda, her initial impression was of something narrow, gloomy, and tired.

It had appeared different the night before, when they had driven along the street for the first time, the baby asleep in the backseat. The sign “For Sale” had flashed in their headlights, and beyond it, they saw three arches aglow in the dark. The house itself was barely visible behind the trees, just a low bulky shape against the paler blackness of the sky, but the lights on the veranda made it seem cozy and warm. “Slow down, slow down!” she cried, but they had already passed. He turned around, and they crept along the street for the second time. It looked even more welcoming then, that yellow light glowing through November drizzle.

At the end of the block they realized that another car had been forced to a crawl behind them for an entire minute.

“They didn’t honk, imagine that,” Paul had said. “Looks like a nice neighborhood. Probably kid-friendly. Honey, I have a good feeling about this one.”

“Yes,” she had said; but what she had liked most about the invisible house with the shining arches was its ambiguous promise, the darkness concealing it. It did not belong to any neighborhood at all, was not pinned down to an address somewhere in the monotonous suburbs of a busy American city, but instead was all shadows and light, and one could just as easily imagine it perched on the side of a lush Caribbean mountain, frangipani trees blooming, ice clinking in the jewel-colored cocktails of a festive crowd on a terrace suspended above the immense mystery of the moonlit sea—or maybe squatting in the deep slumber of a somber medieval village in Portugal or France, all the villagers long asleep, only a solitary poet rocking back and forth on the lit-up porch, his verses slowly adopting the creaking rhythm of the rocker—or even poised as the last human habitation on the edge of a great Siberian forest, yes, a mossy little house out of some old fairy tale, where evening after evening a small, soft-spoken family gathered in the snug seclusion of light to drink tea from chipped cups and talk about birds and stars and books—a house under a timeless spell where everyone was together, and no one was ill, and everyone was happy . . .