Forty Rooms (11 page)

Authors: Olga Grushin

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary, #Contemporary Women, #Family Life

The fire alarm blew up above my head.

Without thinking, I turned on the water, and the room vanished in a hissing cloud of acrid steam. The alarm screamed and screamed. My door was flung open, someone ran in, and, coughing, I watched him pull up the armchair, climb to the ceiling, and unscrew something with manly efficiency.

The noise stopped.

“That’s better,” he said, stepping down. “Lucky I was passing by. What on earth were you doing?”

“Destroying compromising materials,” I said.

“I understand,” he said. “Dirty photographs.” His tone was weighty with mock seriousness, and his eyes alight with laughter in his face.

“I wish,” I said. “My life is nowhere near that interesting.”

“Burning down the dorm seems interesting enough to me,” he said. “I’m on my way to a party.”

“Constantine’s?”

He nodded.

“Watch out for the ouzo, it’s deadly.”

He pushed the armchair back to the wall.

“You should air out the room properly. Need help cleaning up?”

I turned and considered the sink, choked with soggy gray paper.

A charred, half-drowned shred was plastered against the enamel, a few lines still legible.

You can escape this maze if you grow old in it first.

The windows here are transparent walls,

Your fingers stick with the blood of childhood games,

And Ariadne’s thread is a ball of chewed gum . . .

I became aware of his standing next to me, looking at the corpse of the poem, and flushed, and smeared it quickly into wet soot, and hid my blackened hands behind my back.

It had just occurred to me that I remembered every last word of my vanished poems by heart.

“I’m fine,” I said. “Thanks.”

Our eyes met. His face had the broad, clean planes of a Michelangelo nude, and his hair was the boyish, curly mop of a Raphael angel. His eyes were no longer laughing.

“Well, I’ll be going, then,” he said.

“Yes,” I said. “Thanks.”

Still he stood

there.

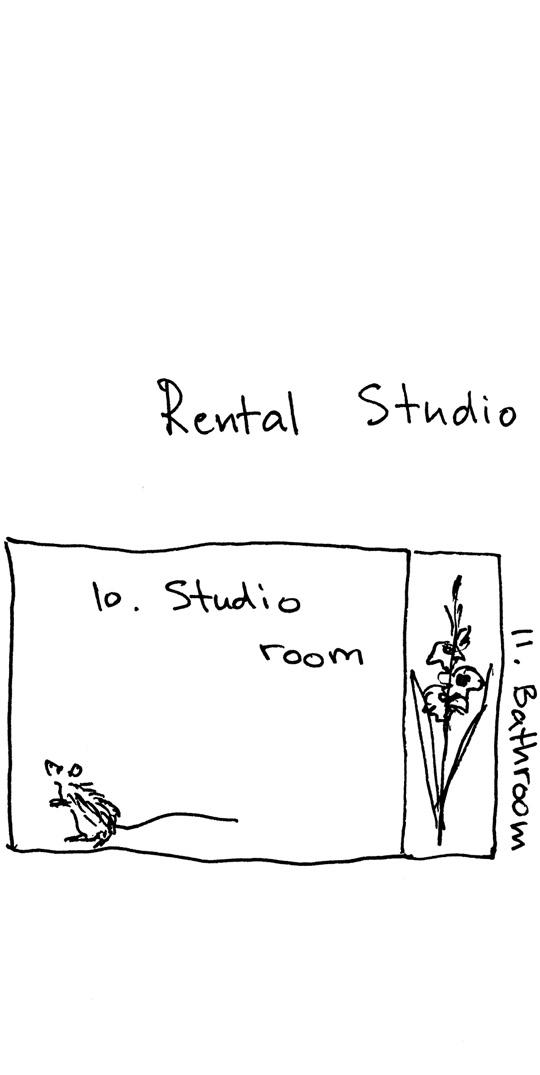

10. Studio Room

Conversation in the Dark at the Age of Twenty-two

Happiness this deep is wordless.

11. Bathroom

A Poem Written at the Age of Twenty-three

I sat on the mattress, my sweater wrapped tightly around me, my arms wrapped around my knees. I felt chilled to the bone. Adam freed a shirt from its hanger, tossed it into the open suitcase, and threw the hanger onto a growing pile; plastic hit plastic with a dry, loud clap. He would not look at me. Through the basement’s two small street-level windows I watched the rain battering dark winter puddles. A woman’s shoes rapped past, sharp and reptilian. I made another effort to speak, though my words felt like ghostly wisps of real words, passing right through him, helpless to change anything.

“Please understand. I followed you up here because of your school, and now you want me to follow you across the ocean because of your job, and I just . . .”

Another hanger smashed into the pile with an angry clatter.

“Please. I don’t want to leave you. Maybe later . . . when you get back . . .”

He looked at me at last. His eyes were dark and flat.

“We were going to spend our lives together.” I could see the jaws clenching in his face. “Now, at the very last minute, I find out that you went behind my back to extend the lease on this dump, and you tell me you won’t be coming.”

“Please. Please listen . . . I just . . .”

“No,” he said, turning away. “I will finish packing and go. I will stay somewhere else tonight. I don’t know where. A hotel. I will go to the airport directly from there.” I tried to interrupt. “No,” he said again, and the force of it was like a hand clamped over my mouth. “I don’t want to say things I’ll regret later. I’ll call you from the hotel. If you change your mind, pack and join me. Otherwise—otherwise we’ll work out the details later, and I wish you well.”

Stunned, I listened to the skeletal clacking of the hangers for another minute, then stood up and, without looking at him, walked into the bathroom and shut the door behind me; there was nowhere else to hide from each other in our cramped closet of a place, and, like a frightened child, I needed to close my eyes so I would become invisible to the horrible monster stalking me through the basement. But the monster got me here just as well. He had already taken his toothbrush and his razor, but in the corner of the bathtub a giant gladiolus leaned against the moldy tiles, its wilting petals stuck out like red tongues from its many maws, mocking me, mocking me.

(“By the time it dies,” Adam had said when he had brought it home a week before, “you and I will be strolling along the Seine.”

“But we don’t have a vase large enough,” I had protested. “Come to think of it, we don’t have any vases at all.”

“So let’s put it in the bathtub. It’ll make for some interesting showers.”

“Do you know, I haven’t seen one of these in years,” I had said. “I remember carrying a bouquet of gladioli on my very first day of school. I was seven, and the flowers were taller than me, and— You’re not listening.”

“I am,” he had said, but I could see that he was thinking about his music again, so I had stopped talking and he had not noticed.)

Crumpling onto the floor by the radiator, I pressed my forehead to the wall, tried to drown out the unbearable clash of the hangers. After a while the noise stopped, all was quiet for some time; then the rip of the suitcase zipper gashed my hearing, and his steps crossed the room—it took only four of his strides to reach the door from the bed.

The front door opened and closed.

Frozen with disbelief, I listened for the turning of the key. But the door flew open instead, his steps tumbled back in, and he burst into the bathroom and kneeled beside me, cupping my face between his hands in just that way he had, and his eyes were no longer dead, and as always, as ever with him, I was overtaken by the warm rush, and everything within me fell into its proper place.

“I can’t leave like this. Tell me. Do you no longer love me?”

“I love you more than I ever thought possible. More than you’ll ever know.”

“Then why are you doing this?”

“Do you remember the first night we spent together, I asked you whether you would prefer to be happy in this life or immortal after your death, and you said immortal, and I said I was the same,

and we marveled at the serendipity of having found each other? Except I fell in love with you, and when I’m with you now, I just want to be happy. That is, I

am

happy, deliriously, astonishingly happy, but I’m also terrified of losing that happiness, and wondering whether you’re happy enough with me, and trying to make you happy, and worrying whether I’m really as happy as I seem to be or whether I’m just fooling myself into believing I’m happy because I don’t want to admit that I’m also a little sad and a little lost, and with all that fretting about happiness, as well as being so exhausted from all the odd jobs I’ve taken to help pay your bills, I barely have the energy for my poetry anymore—but for you, for you it still is all about your music. And what bothers me most is not the knowledge that I need you so much, that I love you more than you love me—although that’s pretty hard to take—but the fact that—”

“Oh, but you don’t! You can’t possibly love me more than I love you. All I want is your happiness, I don’t care about my job, I’ll call them and tell them I don’t want it—”

“Oh no, you can’t do that, it’s your future, our future, I will come with you, of course I will, all I ever wanted was to hear you say that—”

And our lips drew close together, and all was righted in the world, and in another heartbeat I did hear that key turning in the lock—he must have paused on the landing before the closed door for a long moment, perhaps likewise imagining me running after him, throwing myself into his arms, reading who knew what stilted script of unlikely, corny phrases. His steps thundered up the stairs. The springs of the outside door wheezed.

He was gone.

I did not know how much time had passed before I became aware of the deep, all-pervasive cold—at least an hour, probably longer. I was shivering. The radiator was lukewarm under my stiffened fingers, and my legs had gone numb on the icy floor. I felt that I could not move, that my body did not belong to me, and for one mad instant I was possessed by an absolute certainty that somehow, without my noticing, I had died, and was now condemned to spend a meager afterlife trapped in the grimy hell of a narrow, dim bathroom, remembering in an agony of perfect regret the light I had chosen to walk out of, the love I had chosen to lose.

I forced myself to rise and strip. Stepping into the shower, I pushed the gladiolus down into the tub and turned the water on full-blast, as hot as it would go, until it felt scalding, until the steaming stream ran red with the blood of the flower. I began to scrub myself, scrub myself hard, so hard it burned, and at last tears came, big wracking sobs, and still I kept scrubbing, scrubbing the memory of his touch off my skin, the memory of slow kisses in the dark small room, dancing naked to Bach and Django, the threadbare carpeting coarse under our bare soles, our souls always bared, breakfasts in bed at two in the afternoon, feasts of grapes and vodka at two in the morning, reciting Apollinaire and Gumilev to each other—his fluent French, my native Russian, arriving at clumsy English together—candles guttering in pewter holders picked up at a sidewalk sale, conversations intense with questing after truths, the romance of youthful poverty, a three-legged rat scratching night after night at our basement window, boots stomping past, the trembling web of moonlight on the

ceiling, the abandon of nights deep and hard and raw with life, the taste of crisp green apples on his lips, the perfect exclamation point of New Year firecrackers bursting on the street outside just after I said: “Yes, yes, I will.”

In the room beyond, the telephone started to ring.

Leaping out of the shower, naked and wet, heart pounding, flinging open the bathroom door, steam pouring out, damp footprints on the grim gray carpet, not caring who peeked into the bare windows, tearing the receiver off the cradle, breathless from the cold—Hello, hello, are you there, is it you? Where are you, give me the address, stay there, don’t go anywhere, don’t go anywhere ever again, I will come right away, I love you, I will always love you, I can’t live without you—

And as I stood still in the shower, the scalding water running down my back, my breasts, my thighs, the circles of telephone rings widening on the surface of deep winter silence, I watched that other girl through the bathroom door she had left wide open behind her. I watched her flying around the room, pulling on clothes, tossing clothes into her bag, throwing on her coat, running out the door, coming back to pick up the keys she had forgotten, running out again. The girl looked frantic with the relief of happiness—happier, I knew, than I was ever likely to be now—but also somehow less real, diminished. The door closed behind her, just as it had closed behind him.

In the empty room, the telephone stopped ringing.

I turned off the water, dried myself, got dressed, and bent to fish the discolored petals of the dead gladiolus out of the tub.

“When I was seven years old,” I said aloud, “I carried a bouquet

of flowers just like this on my first-ever day of school. We were all supposed to give flowers to our teachers, you see, and gladioli were traditional. I felt ridiculously proud. The teacher had all the new children come up to her one by one, hand over the flowers, and announce in front of everybody what they wanted to do when they grew up. All the boys wanted to be cosmonauts, all the girls wanted to be ballet dancers. When it was my turn, I said that I just wanted to live in a castle full of beautiful paintings and old books. The teacher was indignant. She hissed that it was dangerous bourgeois rot and that she would have to speak to my parents. She made an example out of me, and at recess all the other children called me names and laughed. I was so distressed that I became ill and spent the next two weeks in bed with a fever. My mother read me Charles Perrault’s fairy tales, but my father read me poems. I fell in love with Blake’s ‘Tiger’ and Gumilev’s ‘Giraffe.’ Remember, I translated it for you—

“I see that today your gaze is especially sad,

And your arms, as they hug your knees, seem especially thin.

Listen: far, far away, at Lake Chad,

There wanders an exquisite giraffe . . .

“But ever since then I have detested gladioli.”

I finished stuffing what remained of it into the trashcan, then meticulously rinsed the dark red pollen off my hands, the last traces of the murder committed. I thought about what had bothered me most, about what I could have told him—all the things about art and fulfillment and not wanting a small life consumed

by happiness. The Muses may have been women, I could have complained, but they had still inspired men, had they not? I would have lied, though, about what bothered me most.