Forgotten Voices of the Somme (38 page)

Read Forgotten Voices of the Somme Online

Authors: Joshua Levine

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Military, #World War I

I was let out to a convalescent place because – well – I guess I was improving. It was in this place called

Baglan

, near Aberavon. I was on crutches, and I couldn't do very much. Sometimes the local doctor would come up and take us out to a tea house, and I would sit with my leg stuck out, like a wooden leg, and his daughter would come and have her tea, sat beside us.

In the end, I was sent up to Newcastle. I was still on crutches, and I had to start all over again with my leg. I had severed my sciatic nerve. I have still got a dead foot, and I have always got to wear boots; I cannot wear shoes. They opened my hip up, cut the two ends and sewed them together. Not so long after that, I was walking along the side of my bed, strapped into what they called an 'elephant's foot'. It was an enormous boot. And I made it quite clear that, no matter what happened, I had to be sent to Sidcup for the

plastic surgery

.

So then, I got sent down to the

Queen Mary's hospital in Sidcup

, to have a new nose put on. That took about two years, in total.

Professor Kilmer

was the man I was under. First of all they took photographs. I had to go to a small hut, and I was smothered with plaster of Paris. They made a mask, and when that came out, it showed up every little blemish. Then, they cut down my ribs and they took a lot of cartilage out, and then they buried it in my stomach, to keep it alive. Then they put in into the bridge of my nose, to build it up. The first lot went wrong. Professor Kilmer said, 'What have you been doing? It shouldn't have gone like that!' I said, 'Well . . .

you

did it!' You could talk to the doctors like that. They would do anything for you.

So eventually Professor Kilmer said, 'What do you want? A Wellington nose, or a Roman Nose?' I said, 'I don't care, as long as I get one.' I went into the operating theatre at nine o'clock the next morning, and the next thing I remember is the middle of the night, the next night. All the night staff used to come down and have a rub of the nose, that was what they used to say, they would have a go at the lucky nose: I couldn't raise my head off the pillow. I had two black eyes, a square chin, and a pal went away and fetched a mirror so I could look at myself, but he showed me the magnifying side, and the blinking nose seemed to fill the whole mirror. I was happy with my new nose. I didn't care much, so long as I had one. Have you ever imagined being without one? I was down to nine stone, and the nose used to stand out like a piece of marble. They kept a piece of cartilage, in case anything got knocked off, or broke.

One day, I walked past some kids playing about, and as I went past they got up and galloped past me. I passed two or three streets, and when I got there all the kids in the blinking neighbourhood had gathered. Talking, looking, gawping at me. I'd just had this thing put on! I could have taken a crutch and hit the whole blinking lot of them. I knew what they were looking at, and I turned round and went straight back into the hospital. But then I thought, 'Well it's no good! I could be stuck like this for the rest of my life! I've got to face it sometime,' so I went out again after that; I just walked out. Anytime I wanted to go somewhere, I just walked out. And if people stared, I turned around and stared back.

I never really got my sense of smell back. One nostril is pretty well closed. I got a pair of silver nostrils that I wore for a long time to keep them open, but I got careless. I kept them out for so long, that I couldn't get them back

in again. I always thought if I get another two of them, I could have a pair of cufflinks.

After a time, I was walking without crutches. I had a spring across the front of my boot that lifted the foot, otherwise it would scrape. Gradually, it got better, until I got the lightest boots it was possible to buy; my mum got them in Freeman, Hardy & Willis. In the end, I learnt to walk without it. But I couldn't do very much in the sporting line. That was impossible.

When I got back to Newcastle, I was discharged from the army, and put on a twelve-month outpatient for electrical treatment and massage on my leg. I was thinking, 'What the devil will I do, now?' I didn't want to be like some of them, walking the street with a stick and trying to live on a pension. I found out what the government was able to do. I found what they called an 'Instructional Factory' in Durham, for veterans, and they had a list of things you could go in for: tailoring, cobblering, that sort of thing. I thought if I went for watchmaking, I could sit down. I couldn't stand at the bench, you see. I had to go in front of a board of watchmaker's people, who had shops up in Newcastle, to find out if my fingers were good enough, and next thing I was invited to start at the Instructional Factory. There was instructors there, and I started like an apprentice would, with a file and a square and a block of oak, and I had to square the block of oak. Towards the end, I had to go out and find a job on civvy street. So I went back to

Alnwick

, where I was from. Where I belonged.

I went to this shop where I knew this fellow, and I talked to him, and I served my apprenticeship with him. And by the start of the last war – believe it or not – I was running the shop. Doing the jobs on the bench, doing the office work, estimating and tending to the salesmen doing the orders. He tried to get me to run his bank account and I refused. I said no bloody fear. I was there thirty-odd years.

Looking back, it's hard to explain, but I look back on the war with a certain amount of satisfaction. I was determined to go to war, and I went. It made me a man. I was standing on my feet, and amongst men; I had to stand up for myself. I have had thirty-three operations, but I've never regretted anything in my life. I had a job, and I had a wage. My wife got all my wages, and I lived on my pension, backing horses and playing cards. I didn't do too badly over the years. No. I've never regretted anything – except the death of my wife. That is the only thing I regret. I don't care about anything else.

The

casualty figures

for the battle are shocking. They are very difficult to comprehend, and very difficult to excuse. Nevertheless, the fighting severely weakened the German army physically, mentally, in numbers, and in its ability to fight the war on its own terms. Had the Somme not been fought, Verdun would have been lost and the war could well have drawn to a quite different conclusion, just as General Falkenhayn had predicted.

Mistakes may have been made in the conduct of the battle by British commanders, but does that mean that it was necessarily a mistake to engage in the first place? Or to persevere at such a shattering human cost? Was the British

leadership

demonstrating unforgivable indifference to men whose interests it should have been protecting? Was it pursuing a pragmatic strategy when set against a seemingly inexorable enemy? Similar questions – relating to different conflicts – have arisen since 1916, and they will continue to arise in the future. The answers should concern us: they will always divide us – but the questions themselves may not always be as straightforward as they first appear.

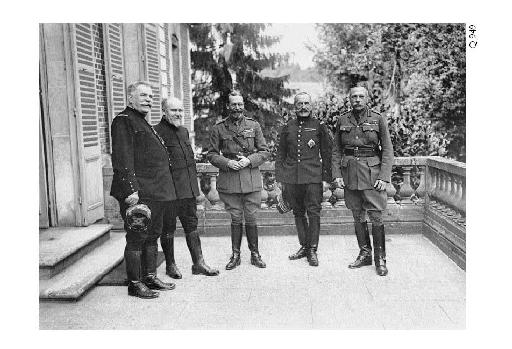

General

Joffre, President

Poincaré,

the King, General Foch and Sir Douglas Haig, photographed on August 12.

A chaplain tending a soldier's grave in the Carnoy Valley.

Index of Contributors

Number in brackets denotes IWM Sound Archive catalogue number. Page numbers in bold refer to photographs.

Adlam, Second Lieutenant Tom VC [35]

Ashurst, Corporal George [9875]

Bewshire, Private Stanley [16463]

Blunden, Second Lieutenant Edmund [4030]

Bradshaw, Private Russell [16474]

Brockman, Second Lieutenant W. J. [24865]

Cameron, Private Donald [16467]

Chapman, Private William [7309]

Cleeve, Second Lieutenant Stewart [7310]

Coldridge, Private Reg [24864]

Collins, Lieutenant Norman [12043]

Critchley, Corporal Jack [4067]

Cullen, Private Philip [24891]

Dickinson, Lieutenant A. [13674]

Dillon, Lieutenant Norman [9752]

Durrant, Sergeant A. S. [13675]

Fellows, Corporal Harry [16470]

Francis, Corporal Frederick [21195]

Glenn, Private Reginald [13082]

Goodman, Sergeant Frederick [9398]

Gordon Davies, Private Leonard [9343]

Hanbury-Sparrow, Captain Alan [4131]

Hastie, Second Lieutenant Stuart [4126]

Hatton, Second Lieutenant [4136]

Hayward, Private Harold [9422]

Holbrook, Private William [9339]

Holmes, Private William [8868]

Howe, Lieutenant Phillip [16469]

Hunt, Sergeant Wilfred [16464]

Jackson, Private H. D. [24858]

Lansdown, Private Victor [10147]

Lewis, Bombardier Harold [9388]

Lewis, Lieutenant Cecil [4162]

Lindlay, Private Frank [16472]

Martin Andrews, Reverend Leonard [4770]

Murray, Leading Seaman Joe [8201]

Naylor, Bombardier James [729]

Ounsworth, Signaller Leonard [332]

Partridge, Corporal Bill [16457]

Pearson, Private Arthur [13680]

Pickard, Private Joseph [8946]

Pilliet, Private Georges [4202]

Polhill, Private Victor [9254]

Quinnell, Sergeant Charles [554]

Renwick, Rifleman Robert [12679]

Senescall, Private W. J. [13681]

Snaylham, Private James [16465]

Staddon, Lieutenant Wilfred [4235]

Startin, Private Harold [16453]

Taylor, Lieutenant William [9430]

Tennant, Gunner Norman [16460]

Woods, Corporal Wilfred [29170]

General Index

Page numbers in bold refer to photographs.