Forgotten Voices of the Somme (31 page)

Read Forgotten Voices of the Somme Online

Authors: Joshua Levine

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Military, #World War I

By this time Tubby was wounded, Mr Firefoot was wounded and that left Captain Cazalet and I. We were the bosses, so we had a consultation on where to site this Stokes trench mortar and we decided to put it about fifty yards back from the barricade. Well, the next time an attack came over this barricade – the usual performance, a man coming over with a liquid fire canister – he got a very, very hot reception. The Stokes trench mortar opened up and dropped the mortars just the other side of the barricade. I'd three men loading up these rifle grenades and I peppered the whole line. I couldn't miss, and, judging by the shouts and the screams, I was taking a very good toll.

All told we had five attacks. The first one was the disastrous one, which we paid very heavily for, but the other four we took a very heavy toll and we didn't lose a man. The strangest thing about this engagement was, although we were right in the thick of it, we didn't have a shell in the whole four days we were there. The artillery were so mixed-up, they didn't know where we were, and where their own men were.

Rifleman Robert Renwick

16th Battalion, King's Royal Rifle Corps

We attacked Delville Wood on August 24. Just before we were due to go over the top, our artillery fell short and a few of our own men were wounded. The officer said, 'I'll be damned if I'll see my men knocked out by our own artillery!' and he took us out and led us into shell-holes before the attack began. That night was my first time over the top, and it was a very funny experience. No-man's-land was a mass of shell-holes. You couldn't see any growth at all. We were jumping from one shell-hole to the next, under machine-gun fire. I remember seeing a corporal, who had fallen, and I looked down at him and I saw that he'd covered his stripes so that he wouldn't be a target. That was a bit foolish. We attacked through the wood, but there weren't so many trees left and it wasn't too difficult to get through. As I was going, I had a vision of being back at school, and our schoolmaster was coming down the path to call us in, and I said to myself, 'If you ever see that place again, you'll be very happy.' The German line was at the back end of the wood and we got to it, but they'd retreated. They'd already gone.

We were sent back to bury the dead of our battalion. Our own pals. I thought a labour platoon should have done it. I've often wondered about that. It was mainly men from the new draft that were sent to do it, and I think they did it on purpose, to toughen us up a bit. One lad had a webbed belt, and a purse, and he had a golden sovereign in that purse. He'd shown it to me a few times and I didn't like the idea of taking it out. He was buried with the golden sovereign in his belt.

It was an upsetting job. When we buried them, the identity discs were taken off and brought back to headquarters. The bodies were buried individually: it wasn't a mass grave – although that

was

done sometimes – but the graves weren't marked. I often think when you see all these cemeteries in France with the names on the graves, I think in many cases the body's not there. But it's nice for the family to think that they're there.

After that attack, a lad who had gone home wounded wrote to my parents, telling them that I'd fallen. He said that I'd come across to see if there was anything I could do when someone was wounded in a shell-hole, and after that someone had shouted, 'Renwick's been killed now!' I remember the incident, but I wasn't killed! My father read it first, and then he handed it to my mother. She had a terrific shock, and my father said, 'Look. We've had a field

card from him since this date, so it can't be right.' It's a bit of a mystery, that one.

Private Harold Hayward

12th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment

I was the colonel's personal runner, and after the attack on Guillemont on September 3, the colonel said, 'Can you take Bacon [the colonel's assistant], and go out to see if you can find the battalion?' So we set out in the direction that the battalion had attacked, in darkness, to see if we could get in touch with them, and find out from the different officers along the line what their situation was vis-à-vis the enemy.

We might very well have been walking into German lines. Alternatively, our chaps might have thought the Germans were coming for a night attack, to get them in the rear. Ours was not a pleasant position. I carried my rifle loaded, ready to fire at a moment's notice.

We walked through the night. We had to jump over trenches and communication trenches, and I thought we ought to have turned back. I didn't see or hear anyone the whole of that night. It was an eerie experience, being out on your own, and not knowing whether you had friends in front of you, or the enemy. The ground was very much cut up, and I was aware of the fact that my rifle was loaded – one up the spout – and I could have fallen into a trench and wounded myself.

When the sun started to rise, I decided it was sensible to get back, at least to tell the colonel that we hadn't caught up with the battalion. I really don't know how far around the radius I had walked – we might have been all over the place. Suffice to say we didn't meet anyone.

At about five in the morning, the colonel told us to have some breakfast and then we went off together. Of course, in the light, it wasn't difficult. We could see ahead, and the colonel said, 'This looks like the battalion!' but not only were there other brigade units mixed up with our chaps – who, of course, we didn't recognise by face – but there were odd chaps from other divisions.

People had become mixed up, but we did learn that the Germans had not made a night-time counter-attack. Our chaps were in small trenches, which they had dug with their trenching tools. I walked along to find my two friends. One – Hull – I found and he was in a bad way because a shell had burst near him. He was pretty badly shell-shocked, and he couldn't tell me about our

mutual friend. But I did find a group of people from my old platoon. I asked what had happened to my other friend, and they said that a shell had dropped in front and buried him. He was in a poor way.

The thing that hit me was that every NCO in my company seemed to have been killed. Those were the days when ranks were distinguished by marks on the arm, and I feel certain that the Germans had people trained to look through field glasses to spot officers and NCOs and then shoot at them.

I was attached to the colonel, but he was in conversation with an officer, who was explaining the situation to him. There was a big gap on our company's right, which they couldn't spread out to cover, and the officer was afraid of the Germans getting in.

So the colonel told me to find out how big the gap was, and how far away the next troops on the right were. They were French, and I was to get in touch with a French officer and learn their plans, whether they had another attack planned, whether they were going to retire, whether the gap could be filled; it was a serious problem. I said, 'Yes, sir!' and wondered whether my fourth-form French would carry me through.

Just at that moment, I got a bullet. I was standing right next to the colonel, looking towards the rear. The colonel was facing the way the Germans were, and I was hit by a bullet that came from the rear, from the captured German trenches. A German had been left behind, in one of their deep dugouts, which hadn't been bombed; he had come out, seen the colonel – and let fly at him. As soon as that happened, he had walked down our reserve lines and given himself up as a prisoner of war. Nobody would have known.

I was wounded in the scrotum. The bullet had come up off the ground, carried dirt with it, gone through my tin of cigarettes, gone through my right low side, got into the crotch and was protruding from my left haunch. I was carried to the dugout that the colonel had decided to make his HQ. I never lost consciousness. The lieutenant put a field dressing on me, and he assured me that just as nature provides two eyes, it provides two of other things. Then he had to go back to see that his machine guns were set up well, and at sunrise the next morning, the stretcher-bearers came and put me on the stretcher and carried me out to where the Royal Army Medical Corps had brought their horse-drawn ambulance.

The ambulance was on very badly shell-pocked ground, and I did admire them for that. There were four of us inside – two Germans below and two

English above. On top, we took all the swing, of course. They took us back to the field hospital, and then from there by train down to a Canadian base hospital. My wound was dressed every four hours – and I broke into a sweat every time I heard that ward door open. The senior sister came up one night at ten o'clock, and she said, 'I want you to keep awake! I am coming to do something about that place down near your privates!' She came in with an orderly and they held one limb each, and she got her tweezers and pulled the shrapnel out.

It wasn't nice at the time, but – my goodness! – I was so pleased afterwards. It meant that they didn't have to come in every four hours to put the dressing on, and turn this

thing

over in my testicles ...

The

Battle of Flers-Courcelette

, which began on September 15, marked the introduction of a new weapon which would – in time – change the nature of modern warfare: the tank. The aim of the battle was finally to wear down German resistance, to pave the way for a breakthrough between

Morval

and

Le Sars

. The

tanks

that were to achieve this aim had been conceived as caterpillar-treaded land-ships, which would combine the mobility of infantry with the firepower of artillery. They would be able to traverse trenches and crush barbed wire, allowing the infantry to follow in their treads. Their name reflects the conditions of total secrecy in which they were developed; they were transported to France, purporting to be mobile water tanks for use by the Russians. In this early manifestation, they were twenty-six feet long, travelled at two miles per hour, and carried a crew of eight. The '

male

' tank was mounted with two six-pounder guns and three Hotchkiss machine guns. The '

female

' had no six-pounders, but carried four

Vickers machine guns

.

For all its promise, the tank of September 1916 was a primitive affair. Visibility from it was poor, armour was thin, noise was so great that the crew had to communicate by hand signals, and the engine was intensely unreliable. Of the forty-nine tanks which arrived in France, only thirtytwo arrived at their starting point ready to roll into action. Of those, fourteen broke down straight away and eight were disabled by shellfire. Two caught fire without any help from the enemy.

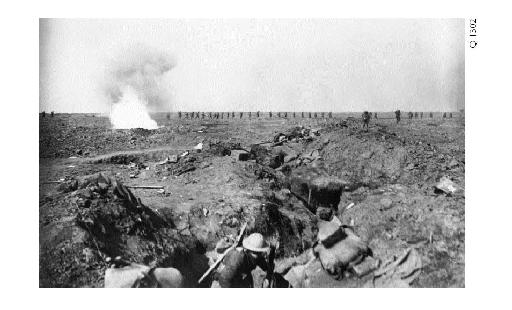

Supporting troops coming under artillery fire as they move up the line near

Ginchy

in September.

Nevertheless, when the first tank – D1, commanded by

Captain H. W.

Mortimore – appeared, German troops surrendered in panic, allowing two companies of the

6th Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

to take an enemy position. The village of

Courcelette

was taken, with the aid of a tank named 'Crème de Menthe'.

Martinpuich

was taken by the

15th (Scottish) Division

, and High Wood was taken by the

47th Division

. Flers was also taken, with the assistance of D17, commanded by Second Lieutenant Stuart Hastie.

One tank commander in action that day – Second Lieutenant

MacPherson – died by hi

s own hand. Having reported a 'broken tail' he turned back, and whilst waiting to give his report he shot himself, leaving a note which read, 'My God, I have been a coward.'

On their first day in action, tanks had probably failed to live up to unreasonably high expectations. Many had broken down and others had failed to keep pace with the infantry. On the other hand, they had inspired genuine terror amongst the enemy, they had bolstered British morale and they had contributed to the most successful advance since the start of the Battle of the Somme: a mile of enemy territory had been taken, over a six-mile front.

Corporal Jack Critchley

Royal Artillery, attached to Guards Division

One day, we were in the wagon line – quite a few of us – and somebody came along and said, 'The war is finished! Just go half a mile down the road, look in a field, and you will see!' He wouldn't tell us why. So we went down and there was quite a crowd there. We saw these 'tank' things that we had never seen or heard of, and the tank men were full of it: 'Oh this is

it

, boy!' and they were describing the tanks to us in full. 'This is a female tank, it has nothing but machine guns, but this is a male tank, it has cannon, and can fire this many shells, and these slots at the bottom of the door are where we point the revolvers through when we are going over trenches, and we kill them that way!'

After that, we thought, 'When we get a few of these lads over, the war is finished! We are going to be home by Christmas!' That was a feeling a lot of us had.

Lieutenant Norman Dillon