Forgotten Ally: China's World War II, 1937-1945 (54 page)

Read Forgotten Ally: China's World War II, 1937-1945 Online

Authors: Rana Mitter

In Chongqing, Gauss was not the only one who perceived the deterioration of Free China. He and Graham Peck were among those who could see that Chiang’s regime, propped up with US dollars, was holding on to power with the greatest of difficulty. The many tentacles of Dai Li’s MSB arrested numerous dissidents and took them off to torture and execution. Chiang was still not in the same class of brutality as that other Western ally Stalin, but by the end of 1943 from the American perspective the Nationalist government was nearly impossible to like and almost as difficult to admire. Gauss noted the “fascist-like” actions that would make it an embarrassing ally for a postwar America.

Yet Gauss admitted that although the political situation was dire, “it would be a mistake to assume that the inevitable result will be compromise with Japan.” Gauss affirmed that the National Government genuinely believed that the Allies would win the war, and “the necessity of being on the winning side.” He also reminded Hull that the Chinese had been fighting for six years and that they were continuing to contain “almost half a million Japanese troops.” He also acknowledged that “war weariness” was a powerful deterrent to further Chinese action. (Earlier in the year, of course, Chiang had admitted, “We are exhausted after six years of our war of resistance against Japan.”)

64

Many Chinese felt that their country had already played its part in the defense of Asia, and that their government should preserve its strength for the postwar settlement, as well as preventing an occupation of the north by the Communists, assisted by the USSR. Gauss also acknowledged Chiang’s great fear that the US might itself make a compromise peace with Japan. There were many reasons to explain the unwillingness of a hollowed-out, battered China to take a more active role in the next stage of the war.

Even with his qualifications, Gauss’s criticism was still not fair. Chiang had made it quite clear that he was willing to take part in a joint campaign in the Pacific. But the suggestion that he should do so while the other Allies concentrated their forces in Europe was disingenuous. In the circumstances it was hardly surprising that Chiang had adopted a defensive strategy. Once again the Allies not only told China that it was a secondary, or indeed tertiary priority, which was understandable in terms of their geostrategic goals, but they also implied that China should act as if it were a first-rank ally while being treated as a third-rank one. The demand was also hypocritical. The Allied strategy was dependent on there not being further action in China in the period immediately preceding the invasion of Europe.

65

If Chiang had really launched his troops in some sort of solo offensive, they would have been destroyed and the Chongqing regime would have fallen even more swiftly, perhaps allowing the Nanjing regime to gain more of a hold in parts of China, or a faster Communist victory.

In a message to Roosevelt, Chiang was frank about his disappointment that the all-out assault in the Pacific would not now take place, and warned that the Chinese people might not believe that Allied pledges of assistance were sincere, particularly in the face of looming economic collapse. Only a loan of a billion gold dollars—along with a doubling of the size of the American air force in China, and an increase in general air transportation to at least 20,000 tons per month—could prevent the imminent implosion of the Chinese economy, and with it, the country’s resistance. Otherwise, Chiang feared, Japan would take advantage of the concentration of Allied efforts on the European front to “liquidate” China.

66

The request was unwise at the very least, and it was taken as a sign that Chiang’s greed knew no bounds. But Chiang can be forgiven for perhaps thinking that cash in hand was better than the vague promises of support that seemed to be written in wind and water. After all, his position, which he had thought so strong at Cairo, had been undermined within a matter of days. It was now clear that Europe, and the plans for Overlord, would dominate the global theater of war in 1944.

As the new year dawned, Chiang did not realize that he would soon be fighting for the very survival of his regime. The decision to concentrate troops on the liberation of France and the push toward Berlin would have unexpected, direct, and very dangerous consequences for China within just a few weeks. And Allied, primarily American, decisions forced on Chiang would make matters even worse.

General Claire Lee Chennault. His “Flying Tigers” were an important morale-booster for Chinese Nationalist resistance to Japan.

General Joseph W. Stilwell (“Vinegar Joe”), Chiang’s chief of staff. The toxic relationship between the two would affect US–China relations for years to come.

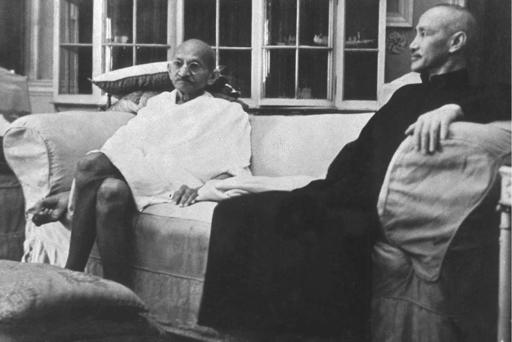

Chiang Kai-shek and Mahatma Gandhi meet near Calcutta, 1942. This was the first occasion that a non-European national leader had visited a major Indian anti-imperialist figure.

Mao inspects Eighth Route Army troops stationed in Yan’an. Communist troops would carry out important guerrilla attacks throughout the war, though they engaged in few set-piece battles.

Wounded Chinese troops, Burma, 1942. The retreat from Burma was one of the greatest humiliations for the Allies in the early part of the joint war against Japan.

Refugees fleeing famine-stricken Henan province, c. 1943. A combination of natural disaster, incompetence, and factors outside Chinese control led to a devastating famine that eroded Nationalist legitimacy.

Female famine victim, Henan, c. 1943.

A Chinese soldier guards a squadron of Curtiss P-40 Warhawk fighter planes, 1943.