Footloose Scot (8 page)

Authors: Jim Glendinning

With my travelling companions from the bus, I too checked in at the former British Consulate, which was now a cheap hotel. Although the area has only recently been opened to westerners, already there were cafes with signs in English and some hotels where someone spoke English. I wandered around the remains of the old clay-walled city, and went to an evening concert by a Chinese orchestra in the new town.

A man was selling home-made ice cream on a street corner, helped by his son. By miming, I suggested he let me help him make the ice cream. This amused him, so I turned the ice cream churn for half an hour, ate some free samples, and he took my photo. Two westerners passing by were also amused, and they bought ice cream cones.

My main interest in going to Kashi was the Sunday bazaar, known throughout central Asia. Actually there are several markets, but I chose the largest just outside of town. I joined a huge crowd of pedestrians being overtaken by riders on horseback or motorbike, calling "boish, boish" (Coming through!). This sprawling make-shift outdoor market was packed with local people from the surrounding countryside. Faces and clothing revealed different nationalities, Uyghurs, Tajiks, Kyrgiz and Uzbeks besides the Han Chinese, reflecting Kashgar's location at the crossroads of Central Asia. Just about anything which might fetch a price was on sale: food, implements, animals, rugs, clothing, kitchen utensils, old bicycles and boom boxes. There were mounds of spices lying on the ground and meat hanging from hooks. The mood was cheerful and the bargaining intense. No one paid any attention to me. Very little had changed here in hundreds of years, I thought.

Elsewhere stalls were selling footwear and hats. I bought two Russian astrakhan winter hats with ear flaps. Bolts of colorful textiles were displayed next to used bike tires, and nearby were skins of exotic mountain animals. In the only space which was clear of people, horses and camels were being walked back and forth by their owners and watched by potential buyers with keen eyes.

After three days I returned by bus to Gilgit. At the Pakistani frontier, one of the tourists, a young German woman, did not have a visa. She was worried about being sent back to Kashi. The Pakistani immigration official, a large man with an impressive handlebar moustache, gave a great laugh and said: "Do not let that worry you, young lady, I Mohammed will grant you a visa on the spot." He took a large rubber stamp and slammed in onto her passport, then with a flourish signed his name. It was nice to observe a personal touch in the normally bureaucratic world of passport inspection.

SOLO TRAVELER

_______

1987

ROUND THE WORLD - AFRICA

BURUNDI

I arrived in Burundi by bus from its neighbor to the north, Rwanda. In those days, each country had yet to experience the trauma of the nineties. Burundi, a small, beautiful and mountainous country, is about the size of Maryland with a population of 7 million, of which Tutsis were 85% and Hutus 15%.

The Burundi capital, Bujumbura, was a ramshackle place with a single traffic light which usually was not working. I found lodging at the home of an American missionary who made a habit of putting up backpackers. This good man arrived from the USA 40 years earlier after two days of flights, including a leg from Newfoundland to the Azores. In Burundi he devoted his life to spreading the word of Christianity, and healing the locals in body through his successful health clinic in Bujumbura.

According to the missionary, the atmosphere in the capital was not easy and there was tension in the streets. He advised me not to get into any confrontation with the locals. I went to a dentist and also had a haircut. Both of these men were tall, slim Tutsis and neither was friendly. Since independence from Belgium in 1962 there had been one genocidal attack, and worse was to come in the 1990s. Even Nelson Mandela backed out of trying to solve the ingrained hatred between the two tribes despite the country's desperate poverty and low life expectancy (48.5 years). For the time being, however, the situation was safe and I had a plan which would take me into the country, far from the capital.

The Burundi tourism authorities had built a small pyramid in the countryside, claiming it marked the source of the Nile. No one believed this but it was a source of interest because of its curiosity value. I decided to go and photograph the pyramid, then make a cross-country hike to Lake Tanganyika before catching a minibus back to the capital - a three day camping trip.

I caught a minibus from Bujumbura which dropped me off at the pyramid. It was a fifteen foot high concrete structure, painted white. Like others before me I signed my name on its side. Checking my guidebook which had a map of the area, I headed off cross-country. I reckoned it was twenty miles or so from Lake Tanganyika. I followed dirt roads through upland countryside with occasional cultivated fields. In the distance I could see the highest peak, Mt. Kikizi (7,037 ft). I stopped at a water hole and joined some of the locals in the cool water. They didn't speak French but they smiled and nodded.

Later I crossed a high plateau, intensively cultivated in small plots. The surprise was that there were very few people, either in the fields or on the road. I had read that the population density was the second highest in sub-Sahara Africa. The weather was dry and the temperature in the mid-eighties Fahrenheit. Later I found a good spot for a campsite next to a waterfall. I was completely alone; there were no houses or people nearby, and I felt quite safe.

Next day I arrived at a village. I was surprised when a young white man suddenly came out of a house. Spotting me, he headed in my direction. He was a Peace Corps volunteer, a conservation specialist, he told me, and was assigned in Burundi to help them establish a national park in the area. I told him I hoped to spend a night alone, deep in the jungle, and asked him where I could do it.

"Follow the trail up that hill," he said, pointing beyond the village. "Bear right to avoid some native houses, then drop down into jungle vegetation where the proposed park is going to be. Go for about two hours, until you pass a large, blasted, blackened tree. Shortly after that look to the right." He had been hacking a new trail out of the jungle at that point which would take me to a water source, a spring and small pond. There I could have my jungle experience. He shoved a machete in my hand and wished me luck.

Encouraged by the easy directions and encouragement, I bought some food in the village, and followed the trail up the steep hill. I continued on a wide mud trail as the vegetation became more dense, the trees taller. The noises from the nearby village disappeared. Sure enough, two hours later I came across a stunted, blackened tree and shortly after that I spotted some branches lying to the side of the trail and a signs of new cutting. This was the trail the Peace Corps volunteer had described. I was on the right track.

It was now early evening so I pressed forward through the forest trees, following slash marks in the undergrowth. The trail started to peter out and the jungle growth to increase. I started to stoop and crawl and was just about to give up hope, as the daylight waned, of reaching the water source, when I heard the sound of running water. I pressed on until in a hollow below me I saw a pool being fed by a trickle coming from a spring.

I collected and purified some water from the pool. In the dusk I found an upended tree and unrolled my sleeping bag in the hollow where the roots had been. This was it; I had my campsite. I had a cold snack to eat and some water to drink. I was ready for the experience of spending a night in the jungle. There were no threatening wild animals or local teenagers likely to rob me. I prepared for the good sleep which I was entitled to. I was tired.

Alas, it was not to be. Just as I was about to drop off, I felt sharp little bites on my legs. My flashlight was weak, but not so weak that it couldn't light up a small army of orange colored ants which had invaded my bag. They were everywhere, I was already bitten on both legs, and my light source was running out. I pulled my bag uphill, and spent much of the sleepless night in the dark trying to kill as many ants as I could with my fingers.

The next morning, tired and irritable, I dragged myself back to the Peace Corps volunteer's village and handed back the machete. He was not there so I couldn't share my story of the ants and get a laugh from him. Later the same day I reached the lakeside town of Mutambara from where I caught a minibus to Bujumbura and checked in at the missionary's house. When I told him about the attack of ants he smiled, but said nothing. Probably he was thinking about how to secure his health clinic in the event of fighting breaking out. I spent one more night, before heading off to catch a ferry at the port of Bujumbura which would take me the length of Lake Tanganyika, the world's longest lake and second largest freshwater lake, and drop me two days later in Zambia. Unknown to me, my travel experience was about to take a turn for the worse.

ZAMBIA

Boarding the Motor Vessel Liemba I found I was sharing a cabin with a Zambian businessman in a suit. Unfortunately, although the lake was smooth as glass and there was no wind, he got sea sick shortly after we got under way and threw up over himself. I loaned him a spare pair of pants while he rinsed his own pants in the cabin wash basin. He bought me supper in the restaurant as a thank you.

The MV Liemba had a long history. Built in 1914 and named the Graf von Gotzen by the Germans who ruled this part of Africa, it was scuttled in 1916 to prevent it falling into the hands of the British. A Royal Navy salvage crew raised the ship and it was reintroduced into service in 1924. It played a fictitious role in the movie The African Queen, as the object of Humphrey Bogart's gin-swilling riverboat captain's attack, which ended the film. Despite its age, it was clean and comfortable.

The boat made several stops going down the lake, pulling in close to the shore but not tying up since there were no jetties. Small wooden boats paddled by women would come out and try to sell vegetables to the ship's passengers. Occasionally, someone would climb up a ladder from one of these boats onto the ship.

I disembarked at Mpulungu, and I caught a ride eighteen miles to the next town, called Mbala. It was getting late. There seemed to be no hotels. I stopped at a shop to buy bread, but the shelves were bare of almost anything except canned potatoes from Ireland. A white man came into the shop to buy cigarettes. He was in his sixties, a little overweight, and his veined red nose suggested a drinking problem. He could have been a character in a Graham Greene novel, the expatriate alcoholic teacher. I asked him if there was any place in the town where I could spend the night.

"Go to the college," he said, "I work there. The boys can give you a bed in one of the dorms." With that he lit a cigarette and marched off. I found the college further along the main street, a cluster of buildings which seemed to me to resemble a rundown boarding school. There was a chapel, an administrative building with a sign reading "Office here" and two long buildings, from one of which I could hear voices. Apart from that, the campus such as it was seemed deserted.

Sure enough, pushing open the door in one of the long buildings I came across a group of black teenagers. There were six of them, wearing the same type of shirt and shorts, sitting in a classroom looking bored. I asked if there was anywhere to sleep.

The students then started to ask questions about me. It seemed that I had arrived at half term. The college was on vacation and all of the students had gone home except this small group. They were eager for conversation, and in no time I had my guidebook out and was showing them my route. They told me that the teacher whom I had spoken was Mr. Richards. He was from England, and taught English.

I was just wondering how I could get something to eat, and when I would get some sleep, when our excited conversation was interrupted by the arrival of one of the teachers, a stern faced man who ordered me: "Come with me." I wondered if this might mean a meal, but I was sadly mistaken.

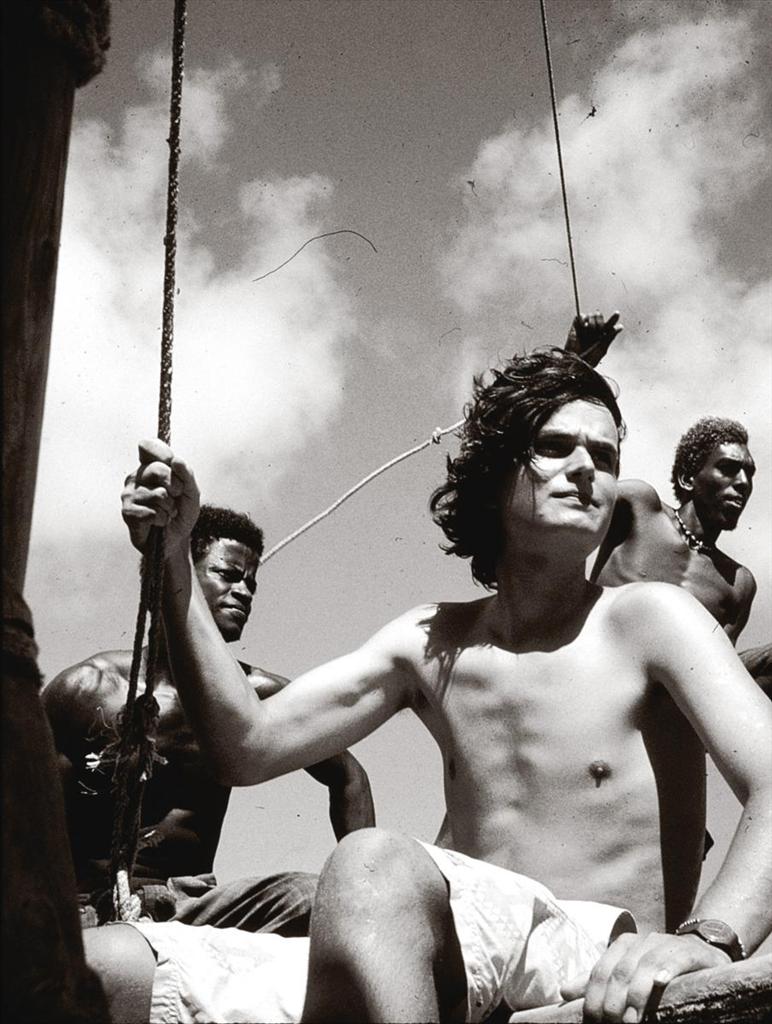

TOURIST ON A DHOW, LAMU

KIDS ON THE BEACH, MALAWI

TRAFFIC LIGHT, BUJUMBURA

We walked across the grassless lawn, and he knocked on a door marked Principal. Inside, an older man, clearly the principal, looked even more severe, and told me to sit down. These two men were upset, and they soon told me why. They thought I was a South African saboteur, since I was white and carried a backpack. I later found that there had been recent incidents in this part of Zambia of South Africans raiding and blowing up buildings.

I was dumbfounded, tired and getting testy. They were accusatory and relentless. I told them how the white teacher had suggested going to one of the dorms; I offered to open up my backpack, and I showed them my passport. I asked them: "Do I look like a military person?" They remain unconvinced, increasing if anything their accusations. Two other teachers came into the room, and joined in the hostile questioning. Then the head teacher said, "You will come with us to the police station."

We formed a small procession of five persons as we left the campus, and headed along the main street. Soon I saw a familiar blue light, the sort that shines outside every police station in England. Inside the station behind a counter was the Zambian equivalent of a British bobby, a grey haired sergeant in a dark blue uniform.

He listened to the outpouring of accusations, in local dialect, as the headmaster supported by the other teachers explained their conspiracy theory. His lined old face showed no reaction. I meanwhile, feeling tired and hungry, simply sat down on a bench while the teachers continued their barrage of accusations. The sergeant asked a couple of questions, and listened to their answers. I was thinking that he was likely getting fed up about being told how to do his job by the teachers. Maybe I would be put in the cells. I really didn't care.