Footloose Scot (4 page)

Authors: Jim Glendinning

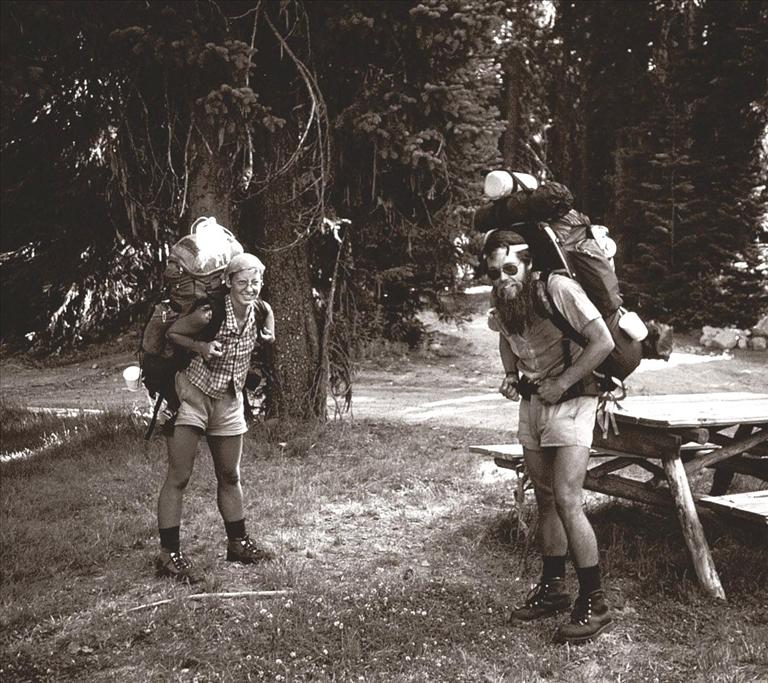

THROUGH-HIKERS

THE MAN WITH THE WHITE HORSE

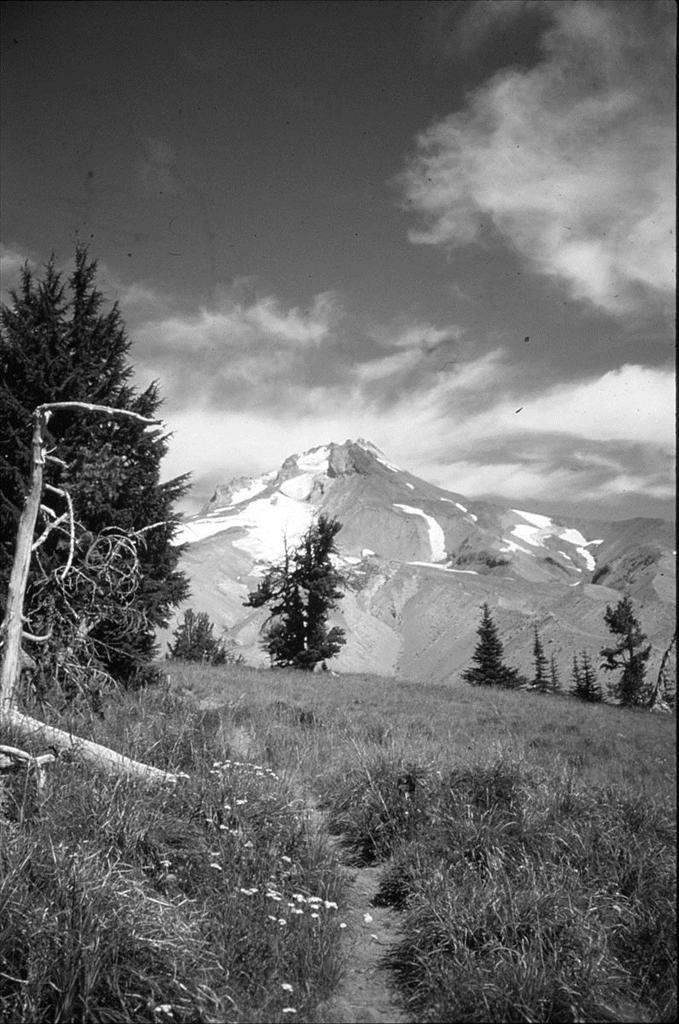

TRAIL, TREE, MOUNTAIN

Later I met a young Californian. Tall and apparently fit, he was picking up a package at a post office near the trail where I had also gone. He opened his parcel, and pulled out some medicine. He explained that he was aiming to do the whole hike in one season. He was one of the approximately 300 tthrough-hikers annually attempting the whole route.

The challenge for through-hikers is that they cannot leave the Mexican border too early, or the snow in the Sierra Nevada will not have melted. Equally, if they are too slow, the fall snow will have started in Washington State, blocking the last few miles to the Canadian border. He was determined to complete the trail but had caught giardia in the early stages of his hike. This water-borne disease comes from drinking water contaminated by animal urine, such as beavers. He told me he felt drained of energy, and relied on the medication being sent him to keep going. Much of the enjoyment had gone out of the trip, but he was determined to reach the Canadian border, and reckoned he would be finished in four weeks. I later caught the disease as a Peace Corps volunteer in Kazakhstan and can attest to its debilitating effects.

At Santiam Pass where the PCT crosses US 20 I decided to leave the trail and head for the towns of Sisters or Bend, to have a meal and buy some fresh produce. A bike race was in progress and there were a lot of support vehicles. I stuck out my thumb and not long after a car stopped. The driver was an older man and he explained that he was connected with the cycle race, a fund raising effort by his church in California. He was going ahead to ensure that their accommodation, which they had booked in Bend, would be ready for the 30 participants.

Somehow this man got to explaining to me in some detail what a difficult time he had had recently with his father, an elderly man close to the end of his life. His wife, the driver's mother, had passed away two years earlier. Since then his father had been sunk in deep gloom, would not eat, would hardly talk - certainly not about his feelings. So the son felt a deep need to persuade his father to give up his hold on life, to let go and to will himself to die. This was an unusual conversation to be having between two strangers, in the Oregon wilderness. But it somehow felt natural, and I felt glad that the car driver wished to confide in me. His message to his father had worked, and the old man had died the previous week. I guess I was the first person he had told. The outdoor location and cycling event perhaps made this an easier time to tell the story and also to tell it to me, an unknown stranger.

I skirted the lodge at Mt. Hood with its parking lots and pressed on for a quiet camp site. Noise and intrusions were now becoming alien to me. I was looking forward to a good meal at the Columbia Gorge, even drooling about what I would choose. Liver and onions sounded good, so did a steak. But would the restaurant have those items on the menu? And would my shrunken stomach be able to cope with a sudden volume of rich meat?

As it happens, I chose a hamburger plate with fries and extra salad, promising myself a slice of apple pie to follow. But in my haste, and maybe also to impress the pretty waitress, I ate too quickly and got an immediate reaction of nausea. I struggled to finish the plate but had no appetite for dessert.

From the Benson Plateau at 4,000 feet to the Columbia River almost at sea level the trail, much of it dynamited out of rock, drops steeply alongside tumbling waterfalls. This is a popular area for hikers, being only one hour's drive from Portland. Fortunately, summer was ending and I passed very few hikers as I descended. I cleaned myself up, ready for a restaurant visit and for crossing the Columbia River on the Bridge of the Gods, a cantilever bridge built in 1926 and named after a Native American legend.

I was now in the State of Washington and at the lowest point on the Pacific Crest Trail. I needed to get my boots stitched before going further. These were canvas, lightweight boots made by Hi Tech. I was lucky to find an old-fashioned cobbler still in business in the first town on the other side of the river. This quiet, white-haired man stitched up my boots in a few minutes and charged me very little. "Here you are," he said, handing the boots back, "These should last just fine." He went on to explain that he got quite a bit of business from through-hikers. Mainly they complained that their leather boots were too heavy, and asked if he sold lighter boots. Most people tended to over-equip themselves, he said, which was expensive and not necessary. He approved of my boots (Hi Tech, with fabric uppers and rubber soles), which lasted me well on the trail and for nine months after.

I now had a steep uphill climb, struggling to regain elevation. The temperature had dropped and low clouds filled the sky. I started to meet hunters on the trail, dressed in camouflage clothing and moving silently. They were bow-hunters who get their opportunity ahead of the gun hunters. None of them were happy to see me; I could only be a liability in their search for prey. We nodded to each other, and passed by silently. It started to rain.

A little further, the weather brightened and I dried out my clothes on some rocks. A pack train approached from the opposite direction, four horses each pulling a loaded mule. All the equipment looked top quality, and all the riders were dressed in check shirts, windbreakers, cowboy hats and chaps. The lead man stopped and affably asked where I was going. He then said his group planned to stop and fish for trout in a lake I had just passed. "The first is for you," he offered, if I cared to wait. I turned back, and hung around for an hour, but alas no fish were rising that day. Still, I appreciated the offer.

The rain started again, more persistently. Next it turned to sleet. I plodded on for a few days and, beyond Snoqualmie Pass, I met up with some other trail users who had come out for the weekend. It was raining hard, my tent was wet, my sleeping bag was also wet, and my morale was low. I had lost weight and energy. Two days earlier, I had tripped over a tree root and fallen on my back. I was temporarily stuck, like a bug with its legs in the air until I was able to roll over and get onto my knees. When the weekend guys, who had to get back to work, offered me a ride in their car to the nearest town, I took it.

I cleaned up in a room I rented above a restaurant in Skykomish where the weekend guys had dropped me, and started to enjoy having someone else cook my meals, and not having a daily mileage quota to fill. But first I wanted to get to Lake Chelan, a noted beauty spot. So I hitched east on US 2 towards Wenatchee. To my surprise, I saw the same couple of long distance hikers I had met on my third day also hitching a ride. I met up with them later on the boat ride on Lake Chelan and asked them why they had quit. They said they simply had had enough. They didn't feel that reaching Canada, three weeks' hiking away, was vital to their satisfaction. The cold weather was due to start, and they had had enough cold weather in New England the previous winter. Certainly they didn't look like people defeated by the elements. Nor was I; I had had more than a hike, covering 600 miles in six weeks. I had had a learning experience and a small adventure.

What I got out of the six weeks was a good fitness workout. Although I had lost an unnecessary amount of weight thanks to an inadequate diet, I felt strong and fit. More important, I got my head cleared of negative feelings concerning my failed business, realizing there were more important things such as good health and environment. The huge expanse of forest and wilderness areas in Oregon reminded me that the USA is a continental country in size, and the relatively few people I met along the way were testimony to the hardiness and variety of Americans. The thing I regret is not slowing down, doing some fishing and spending more time with some of the people I met, particularly the fellow with the white horse. But, refreshed in one sense and exhausted in another, I was now ready for a different sort of solo travel - around the world.

SOLO TRAVELER

_______

1987

ROUND THE WORLD - ASIA

HONG KONG

Thirteen hours after leaving Vancouver, the Air Canada Boeing 747 eased down onto the runway at Hong Kong's Kai Tak Airport in Kowloon. As we slowly lost height I could see a family of four sitting round a table eating supper in one of the tenement buildings near the runway. It was 1987, and I was on the first stop of a round-the-world trip, starting in Houston and heading for Asia and Africa, expected duration: eight months.

From the airport I took a bus to Nathan Road, Kowloon to find a room. I had read about Chunking Mansions, a legendary haunt for backpackers. The name Mansions is misleading. Comprising five blocks and rising seventeen floors this is a city in miniature, consisting of snack bars and curry restaurants, tailors and sweatshops, money exchange offices, travel agencies, retail shops of all sorts on the ground floor and on the upper floors cheap accommodation.

I already knew where I wanted to go, so I edged past the crowd of touts of many nationalities hanging around the main entrance to the Mansions. This motley crew of entrepreneurs hoped to steer a new tourist to a specific hotel or camera shop and earn a commission, or sell drugs or women or anything else. I took the lift to the fifth floor and rang a bell outside the Heavenly Gate Hotel. My room, more like a cubicle, had a shower and toilet and a single bed above which a TV was bolted to the wall. A window looked out onto a ventilation shaft. But it was clean and secure, the price was right and I was centrally located in Kowloon within walking distance of the Star Ferry to Hong Kong Island.

Hong Kong is a place which cannot be spoiled whatever else is added. The location is outstanding. It comprises an island, a piece of the mainland fronting onto the South China Sea and some smaller islands. It is a westernized commercial and banking center on the flank of China. Its many tall buildings are evidence of the colonizers' entrepreneurial success and the tenements of Kowloon speak of a Chinese city. The city sucks you in and you might as well submit to noise, odors and crowds.

I took the Star Ferry from Kowloon across the harbor to Central, the downtown area, and headed for the Peak Tram. This funicular railway, built in 1888 and pulled by a steel cable, smoothly transported me almost vertically 1.4 kilometers to the summit, Victoria Peak, in eight minutes. From the top the whole wondrous spread was visible. I could see the Star Ferry now in miniature and other small boats crossing Victoria Harbor. In the foreground a dense cluster of skyscrapers soared upwards. In the distance Kowloon and the New Territories stretched towards the China border. I was lucky to see so far since on many days mist or low cloud can obscure the view from the Peak, which is Hong Kong's most popular attraction.

Shopping, the number one concern for most tourists, interested me not at all except to buy a camera. But I enjoyed prowling the streets, exercising all my senses, particularly smell. Every street was busy with bustle and noise, especially car horns. Many business transactions took place on the sidewalks, including eating. People moved purposefully since there was work to be done and money to be made. To sit in the quiet, dark interior of the St. John's Anglican cathedral, scanning the plaques on the wall commemorating the lives of former governors and military men, then to exit into the clamor of Hong Kong's streets, is about as great a contrast as you can find. Long a British colony, its days were now numbered. The takeover by China would not take place until 1997. For now, the imperial presence was still visible here and there (a Union Jack flag on a pole, a British uniform on the police, a cricket game). A sign on the red brick Clock Tower near the Star Ferry, which was built in 1916 as part of the railroad station, tells the reader that he could board a train there for London.

I came back to Hong Kong in 2010 on my way to Malaysia. A huge new airport on Lanau Island had replaced Kai Tak. After efficient and speedy processing by Chinese Immigration I stepped outside the terminal building. There I found exactly what I wanted, a local bus which took me to Nathan Road, Kowloon for Chung King Mansions again. Shady characters of many nationalities still hung around the entrance to the mansions, and the upper floors still offered closet-size rooms.

Walking the streets of Kowloon and Hong Kong Island the next day, the place seemed even more dynamic and crowded than previously. The British trappings had gone, but they had been superficial only. Hordes of mainland Chinese (over 22 million annually) were now visiting an exotic corner of their country which previously was off-limits. The tourism authorities were advertising crime scenes as an attraction, something I doubted the British would have done. I loved it. Hong Kong was not just as good as ever, it was better than before.

THAILAND

I was travelling with a backpack on a tight budget when I visited Thailand in 1987. Following the instructions in my guidebook, I walked out of Don Muang Airport, the old international airport, crossed the highway and walked 200 yards to a small rail station where I caught a second class train into the city center. My first impression of Thai people was their good natured tolerance as I heaved myself and my big blue backpack onto a very crowded train.

At Hualampong train station, following again the instructions in my guidebook, I looked for footprints painted on the sidewalk outside of the main entrance. I found them as well as the name of the place I was looking for. I followed the footsteps for a few blocks, turned right down a lane, and then I saw the same name on a gateway. Pushing open the gate I entered a garden and walked to a desk inside the entrance door, under the gaze of some backpackers lounging on chairs. I had found my base in Bangkok, a typical backpacker's hotel, which was to serve me well over several visits.

The guidebook I carried was Lonely Planet's guide to Thailand, written by Joe Cummings. Only three years later the author himself arrived on the doorstep of my Bed & Breakfast in Alpine, Texas. This time he was writing a guidebook to Texas. The guide to Thailand, first published in 1981, had sold millions.

MAKING ICE CREAM IN KASHGAR

IN A NEPALI CAFÉ

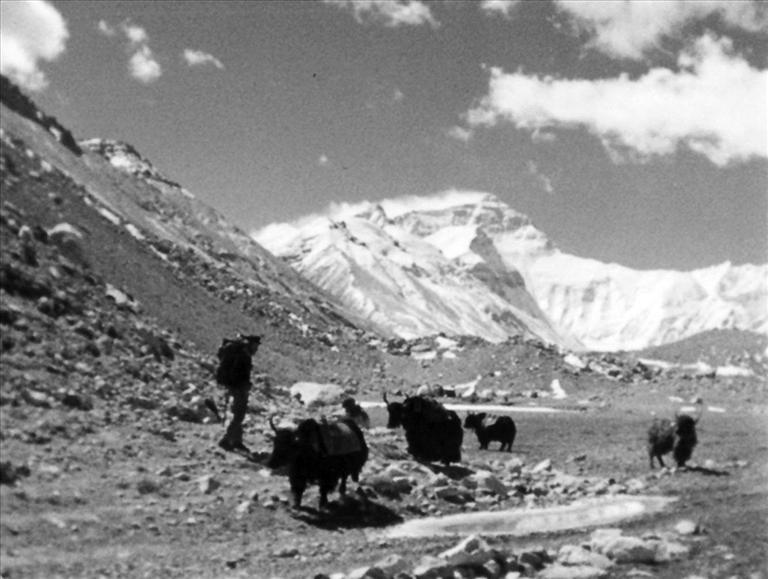

AUTHOR, YAKS, EVEREST

SCHWEDAGON PAGODA

He was to write a good number of other guidebooks including guides to Northern Mexico and Bhutan and earn himself the reputation of being one of the best guidebook writers in the world. By the time I met him again, in 2009, he had largely given up guidebook writing and was playing music, and later became Deputy Editor of The Magazine at

The Bangkok Post.

He had mastered a demanding job, being constantly on the move and requiring quick and accurate notation of mundane facts, and also being alert to spot the telling difference or a revealing feature of a place. Behind his easy going manner was a sharp eye and keen memory.

Thailand has a good railway system. I've travelled by train east to the Laotian border, north to Chiang Mai, and south to the border with Malaysia and then on to Singapore. But I have a particularly fond memory of the overnight train to Chiang Mai, air-conditioned and with comfortable berths. They even bring a meal to you. There is time to watch the passing countryside until it gets dark and the clacketty clack noise of the wheels on the railroad track lulls you to sleep. This is a good way to arrive, slowly and after a good night's rest, compared to the crowded flights and herd operation of the discount airlines.

Anything is better than Thai long distance buses. I've been on too many Thai buses driven at breakneck speed down the center of a two lane highway because the bus driver believes he is king of the road. On an overnight bus trip from Bangkok to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, three hours into the trip and close to midnight, the bus I was on stopped due to a traffic accident. The police had illuminated the crash sight with their headlights. A bus had hit a car, and skidded to one side. The car had been opened up like a can, and three dead bodies were visible. The limb of one of the occupants lay on the road surface. The German girl in the seat next to me leaned across to look out. I blocked her view, and said to her: "You don't want to see this."

Chiang Mai has always felt special to me. It's a modern city of 160,000 in the north of Thailand at an altitude of 1,000 feet, the cultural capital of Thailand. The center is easy to cover on foot and is packed with restaurants, a wide choice of accommodation, bookshops, coffee bars and outlets for Thai arts and crafts. There are tours by elephant, many varieties of cooking course, zip-line flights through the tropical forest and a choice of massage and other treatments at its many spas. Despite the huge number of tourists (up to 5 million), it has managed to absorb them and keep its special charm.

I took a hike to the hill tribe villages near Chiang Mai. It's not a thing you can easily do yourself, and the prices are competitively low. There are seven ethnic minorities in Thailand like the Karens and Hmongs, each with different tribal dress and customs. I signed up for a three day trip which would include a night in the settlements of two different tribes.

There were five in our group, two Canadian men, a young German couple and myself. We were dropped off on the main highway north of Chiang Mai and cut across hilly, wooded terrain in hot but manageable temperatures. Our guide was a young Thai wearing a cowboy hat. He seemed new to the job and uncertain of the route, but kept up a cheerful commentary about our surroundings. He carried a tray of a dozen raw eggs for our supper as well as his pack.

By early evening, when conversation had dried up and fatigue set in, we came to a village of wood and bamboo houses set on stilts. We climbed up a ladder into one of the houses and our guide talked with the owners who nodded and smiled at us. This was to be our accommodation for the night and we stretched out on mattresses which were unrolled on the floor of a large, clean, unadorned room. A pig rooted around below us looking for scraps and the occupants, the women elegant in black and red embroidered jackets, moved out to another hut. Obviously this was standard practice, and we were a useful source of income.