Fooling Some of the People All of the Time, a Long Short (And Now Complete) Story, Updated With New Epilogue (31 page)

Authors: David Einhorn

Tags: #General, #Investments & Securities, #Business & Economics

Brickman also found that BLX made a $480,000 SBA-backed loan to Master Chase Enterprises for two old shrimp boats in 2001. When the loan showed strain, BLX tried to defer the problem by making a second SBA-backed loan for $40,000. After the boats’ owners filed for bankruptcy in 2003, BLX repossessed the boats and sold them for a total of $60,000 in January 2004. Brickman estimated that once fees and other costs were figured in, the loans had a loss of about $500,000. He also noted that the SBA had not taken a charge-off on the $480,000 loan as of the end of 2006. This was typical of BLX: delay charge-offs in order to manipulate SBA lender statistics.

Brickman generated detailed and well-documented write-ups for every defective loan he found. He discovered abundant evidence of impropriety. He concluded that BLX violated many SBA policies, including making loans to borrowers who were already in default on debt to other lenders; not verifying equity injections; inflating collateral values; and using false or doctored bills of sale to support fictitious transactions.

Even when the SBA happened to find problems with BLX, it favored a “lender-friendly” approach. On November 4, 2004, SBA’s OIG provided BLX with a list of “paid in full” loans that had been improperly paid off with the proceeds of a new SBA loan. BLX responded on November 15, and conceded that the loans were ineligible and volunteered to repay the government for two of the loans. The SBA Loan Programs Division responded that it “. . . appreciated the lender’s offer to repay the guaranties . . .” but that it was imposing too harsh a penalty on itself and recommended a “repair” instead.

In one of the loans, Yogi Hospitality purchased a Ramada Inn in Petersburg, Virginia, from Host and Cook, Inc. in December 2000. The SBA loans to both entities were originated in BLX’s Richmond office, headed by McGee. In the documentation, BLX had failed to identify the loan as a change-of-ownership transaction or that there was an existing SBA loan to the seller. In response to the SBA’s suggestive e-mail, BLX decided not to reimburse the SBA for that loan and claimed the borrower had made all principal and interest payments for three and a half years until March 2004, when the borrower ran into financial difficulties.

In contrast, a subsequent report by the SBA’s OIG found that six months after funding, BLX granted a deferment so the borrower made no principal payments from June 2001 to July 2002 and during other periods. Further, “the lender also neglected to mention” that the loan was a $1.33 million second mortgage behind a $1.6 million first mortgage held by Richmond Bank, and also failed to mention the property had been appraised at $3.6 million at origination, but had been reappraised to only $940,000 in August 2004. The SBA loan was a complete loss.

Brickman and Greenlight filed a “whistle-blower” suit relating to the shrimp boat loans in December 2005 under seal, as required, so that the government can conduct a confidential investigation before notifying the defendants. Due to the fact that this litigation is currently on appeal, there are some aspects that I am not permitted to discuss at this point. As a result, I have limited the narrative and excluded parts of the chronology, documents, and interactions with the government. I don’t believe any of the excluded material is exculpatory to Allied or BLX in any way. But it is important for you to know that this discussion is not quite the full story.

Greenlight’s lawyer and I flew to Atlanta (where the case was filed) to meet with Justice Department lawyers and an investigator from the SBA’s OIG. Under the False Claims Act, it is standard protocol for them to meet with the “relators,” as the whistle-blowers are called. They met with Brickman a few weeks later. After some basic questions about me (they wanted my resume), what we do at Greenlight and our relationship with Brickman, I walked them through our problems with Allied and the company’s long campaign of attacking us. I gave them the whole history. The meeting lasted for about an hour and a half.

A month after our meeting, our lawyer heard from the Justice Department lawyers, who, after consulting with the SBA, were under the misimpression that the entire loss from BLX across the entire program was only $3 million! That figure made no sense—it should have been in the tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars. The Kroll report alone found more fraud than that, and those were only a small percentage of the company’s loans. The fraud was certainly more prevalent and damaging to taxpayers than $3 million. Dissatisfied with this figure, Brickman found out the losses. It took him a while, but paperwork, government bureaucracy, and time have never hindered him. He filed a series of Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to the SBA relating to BLX defaults.

Greenlight also filed a few FOIA requests. We asked for access to BLX’s regulatory filings. The SBA denied this request because release of the information “may pose harm to the lender.” In contrast, banks and insurance companies also must make regulatory filings. These filings are public documents. As a result, Greenlight appealed to the SBA and argued, “[We] believe that there is a public interest in releasing this information that outweighs any potential harm to this particular lender, as [we are] investigating whether this lender has committed fraud against the SBA.” The SBA denied our appeal.

In 2003, the SBA had announced that it would create risk-ratings to monitor individual lenders. So now we requested that the SBA release the risk-rating and related analysis for BLX. The SBA denied our access again, for the same reason. It also denied our appeal.

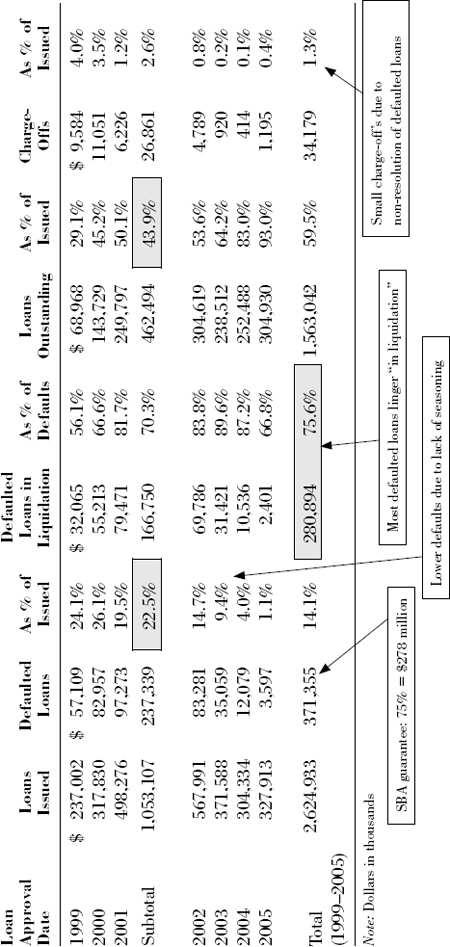

Eventually, the SBA provided Brickman with access to BLX’s loan history. It took him months to get clarifying information. He also found a database of SBA loans at the University of Missouri School of Journalism. We were able to extract the BLX loans and sorted them by year of origination and status. What we found was even beyond what we expected (see

Table 23.1

).

Table 23.1

Includes Loans Originated by Allied Capital SBLC, BLX Financial Services, Inc. and Business Loan Center

Sixty days after a loan becomes delinquent, the SBA honors its guarantee by “purchasing the guarantee.” The “Purchased Loans” column shows the loans where the SBA did that. The SBA only has to pay on the guaranteed portion, so its actual outlay is generally 75 percent of the purchased loans. After the SBA purchases the guarantee, BLX continues to try to collect on the loan. During that period, the loan is in a limbo status called “liquidation.” When BLX resolves the loan, it remits 75 percent of whatever it recovers after expenses back to the SBA. At that point, the SBA charges-off any remaining balance.

The SBA data showed that in BLX’s oldest loans (1999–2001), the SBA paid up an average of 22.5 percent of the time. The “Outstanding Balance” column shows that from those years 43.9 percent of the loans remained outstanding. The high purchase rate combined with a significant amount of remaining balances suggested that the eventual default rate could eventually reach 30 percent or more. The data showed that in more recent years, there have been fewer defaults, probably because there has been less time for defaults to develop. Since 1998, the SBA has paid out almost $280 million (75 percent of $371 million) in loan guarantees on BLX loans. That’s almost

one hundred times

more than the Justice Department found or was told by the SBA.

We suspected that the SBA’s inaccurate claim of small losses might have come from the agency’s not regularly charging-off the loans that went bad, but it also might have been someone within the SBA trying to protect BLX. About 75 percent of all the BLX loans where the SBA paid the guarantee had not been charged-off on the agency’s books. The loans instead remained in liquidation. It was up to BLX, not the SBA, to determine when it had completed every effort to collect. Of course, many bankruptcies take time to resolve. It can take years to resolve a complicated disaster like Enron, satisfy all the creditors, and handle all the things needed to reorganize or liquidate a company. However, these SBA loans are much simpler loans to convenience stores, gas stations, car washes, and motels. They are generally backed by a single property and a personal guarantee. When the loans default, it shouldn’t be a long process to foreclose on the property, hold an auction, and pursue the personal guarantee. It’s hard to see why this should normally take more than a year.

The simple matter was that the SBA wasn’t making its lenders charge-off the loans. This allowed the SBA to defer losses on its books—making the entire program look better than it was. Standard government accounting procedures would require the SBA to book its losses when it pays out on the guarantee. The SBA doesn’t report the results of its program on that basis. I suspect if it did, Congress would better see the enormous risk the program creates for taxpayers.

The effect of the SBA’s policy is that unscrupulous operators like BLX can defer losses on their own books for years. As long as BLX claimed it was trying to collect, it accrued annual servicing fees that it would get to eventually deduct from any recovery it passed back to the SBA. Carruthers heard from a former BLX employee that the company would sometimes create an inflated appraisal for the file to justify its carrying value and then hold the defaulted asset indefinitely, sometimes leasing it for “rental income” instead of liquidating it. Worse, Brickman found loans where the borrower filed and exited bankruptcy and even though the SBA debt was discharged, the loans remained classified as “in liquidation” rather than charged-off. It is hard to see how either the SBA or BLX was following its respective accounting rules.

By leaving the defaulted loans in the purgatory status of “liquidation” indefinitely, BLX was able to claim it had a low “loss rate,” which it touted to regulators, the securitization market, and investors as evidence that its portfolio performed adequately (recall that BLX claimed to have less than a 1 percent average annual loss rate). BLX also structured its securitizations to permit it to repurchase defaulted loans out of the collateral pool, reducing the reported losses in the pools, but leaving the defaulted loans on BLX’s books. Not only that, but on the few loans that it did charge-off, BLX had a relatively high recovery rate. This could easily have been a voluntary decision by the company, where loans with a good recovery were posted and resolved, while those with little chance of recovery lingered. Some of the good recoveries may have come by engineering property sales to new buyers financed by fresh loans.

The SBA measures success by how many loans it originates, how many businesses it helps. Every year it puts out a press release proclaiming the amount of support it provides. The SBA also is often criticized when it doesn’t make enough loans fast enough, such as after Hurricane Katrina. I believe the SBA took a “lender-friendly” attitude toward BLX because the company, by pumping out the loans, was making the agency look good. It also didn’t hurt that Allied, BLX and/or their high-priced lawyers aggressively lobbied the agency to ignore complaints from profit-motivated short-sellers, as we heard repeatedly from many regulators.

When we demonstrated that the losses far exceeded $3 million, the Justice Department continued its investigation into our

qui tam

complaint. The department has ninety days to decide if it will intervene, but it commonly asks for extensions, which it did with us several times in order to complete its investigation. We could have rejected their request, but that would mean we would have to pursue the case on our own. So we gave them more time.