Fooling Some of the People All of the Time, a Long Short (And Now Complete) Story, Updated With New Epilogue (25 page)

Authors: David Einhorn

Tags: #General, #Investments & Securities, #Business & Economics

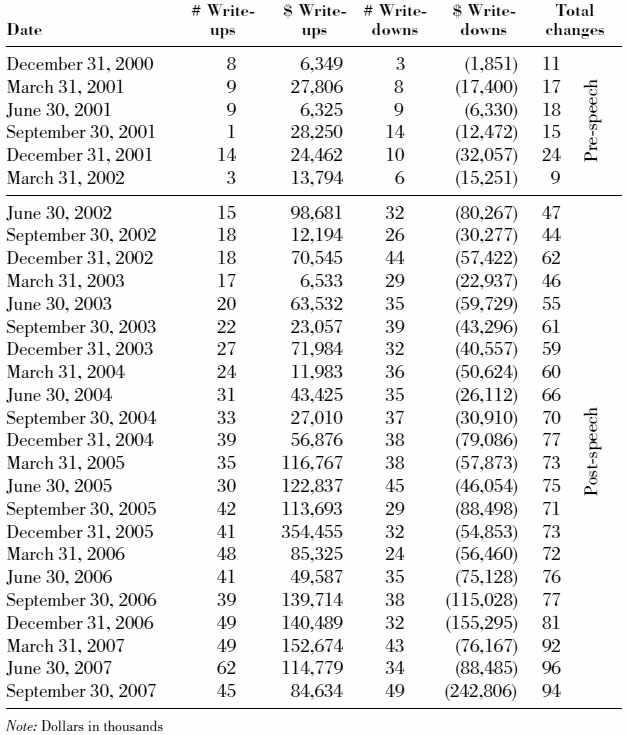

For the statistically minded, the data in

Table 20.1

showed a 99.9 percent confidence level, a correlation of 0.95, an R-squared of 0.9, and a

t

-statistic of 8.8. For the non–statistically minded, that is about as certain a conclusion as you can have in statistics.

Table 20.1

Write-ups and Write-downs Recognized Each Quarter

On the July 29, 2003, Allied conference call, notably, Houck, the Wachovia analyst, asked Allied whether the increased number of mark-ups and mark-downs in the most recent five quarters indicated a change in the valuation methodology. “You know, actually I think it’s more related to the economy than anything else. The valuation practice is the same as always,” Sweeney fibbed.

We did another statistical analysis demonstrating that Allied smoothed its investment performance rather than independently valuing each of its investments. The amount of investments written up each period correlated with the amount written down each period. (The correlation was 0.93, R-squared was 0.86, the

t

-statistic was 7.4, and the confidence level was 99.5 percent.) The relationship grew even stronger in the five quarters after Allied changed its accounting in June 2002. (The correlation was 0.99, the R-squared was 0.98, the

t

-statistic was 13.4, and the confidence level was 99.9 percent.) This meant that Allied artificially “managed” its write-ups and write-downs.

Write-ups and write-downs should be negatively correlated, or inversely related, because moves in the economy and capital markets generally occur in only one direction per period. As Allied’s portfolio investments were positively correlated with the economy, the values of write-ups and write-downs themselves should be negatively correlated. In a strong economy, there should be many write-ups and fewer write-downs. Conversely, in a weakening economy, there should be many write-downs and fewer write-ups. Our analysis showed that Allied did the opposite in order to fabricate smooth performance: Allied wrote-down its problem investments

gradually

over time and matched them with offsetting gains as they developed.

We did a third statistical analysis that showed a serial correlation between current and subsequent changes in the value of Allied’s investments. The data showed a 99.9 percent probability that initial write-downs of investments are disproportionately followed by further write-downs of the same investment. If management were marking the portfolio fairly, then future adjustments should be independent of prior adjustments. No pattern should exist and write-downs should not beget further write-downs. Just as we saw in Sirrom years before, the only conclusion to make was that Allied was slow—intentionally slow, profitably slow—to account for bad news.

That was more than just bad behavior. It is

illegal

for investment companies to smooth their performance by matching winners to losers and belatedly recognizing problems. This inflates the earnings and the balance sheet. Allied’s practice of delaying write-downs enabled them to dilute the eventual impact of the losers by repeatedly selling additional equity in the interim. Also, it gave investors a false impression that the investment results are smoother, more stable and less risky than they really are. The statistical analyses showed that this was not a case of a few isolated anecdotes of inflated valuations, but a broad, systemic pattern of reporting manipulated and misleading results. Some frauds are more obvious than others. Because this one seemed too sophisticated for regulators to catch, we tried to give the government a statistical analysis, which would make it clear, even to them.

Along with the statistical analysis showing how Allied illegally smoothed its portfolio performance, my SEC follow up letter contained a lengthy discussion of BLX, noting Allied’s high purchase price of BLC Financial (Allied paid four times book value, and an unusually large premium to the pre-deal trading price) and pointed out that even as Allied reported interest and fees from BLX, the subsidiary burned cash. The money path was circular: Allied extended additional investment to BLX each quarter. Allied began to disclose some summary financial information for BLX in the June 2002 quarter and had then made a full year of those disclosures, which showed that BLX’s loans did not have the cash economics that Allied promised at its investors’ day in August 2002. Cash premiums on loans sold averaged only 4.3 percent, rather than 10 percent. Residuals grew $56 million in the year, compared to earnings before interest, taxes, and management fees (EBITM) of $44 million, meaning 126 percent of its EBITM was non-cash. This meant that BLX generated no cash to pay Allied: All of Allied’s “revenues” from BLX were funded by Allied putting more cash into BLX.

Even as origination volume and EBITM hadn’t changed much and Sweeney insisted on the July 29, 2003, conference call that Allied valued BLX using the same valuation process, Allied increased BLX’s enterprise value to $465 million as of June 30, 2003, from $390 million the previous year.

Allied recognized “unrealized appreciation” of $50 million in its BLX investment that quarter. Since Allied reported $59 million of net income that quarter, the BLX mark-up was most of Allied’s earnings. The write-up more than offset sizeable write-downs from four other investments: $14 million from Executive Greetings, $10 million from ACE Products, $8 million from Color Factory, and $7 million from Galaxy American Communications.

Allied explained that part of the increase in BLX’s value came from an increase in the multiples of comparable companies. The multiples did expand in the June 2003 quarter from the March 2003 quarter, and on the second-quarter conference call Allied cited the higher public multiples to justify the enormous write-up of BLX’s value—even though its operating results had not improved. However, in the September 2002 quarter, comparable company multiples had fallen an average of 32 percent and conveniently that decline did not cause Allied to write-down BLX. All told, the multiples in June 2003 were lower than in June 2002. We didn’t know how Allied changed its valuation methodology for BLX, but certainly it did.

The following quarter, Allied disclosed that it changed the comparable companies it used in its analysis. Allied dropped DVI, Inc., which went bankrupt, and replaced it with additional companies that used portfolio lending accounting, including HPSC Inc., GATX Corp., and Capital Source. This was the first time that Allied identified the publicly traded comparable companies in an SEC filing. Allied said on the conference call that the comparable group was “about the same,” but it had actually changed dramatically.

Finally, the letter to the SEC discussed Allied’s other investments in Hillman, GAC, Startec, Fairchild, Powell Plant Farms, Drilltec, the CMBS portfolio, and Redox Brands. We reminded the SEC about the experience of Todd Wichmann, the Redox chief executive, who said Allied asked him to falsify his company’s financial statement to avoid problems with the senior lender. We also summarized Kroll’s findings about American Physician Services.

“Simply put,” I wrote, “in our view, Allied continues to engage in valuation and accounting fraud, and then attempts to disguise its valuation practices through the dissemination of misleading statements. This practice is repeatedly demonstrated in investment after investment.”

The letter continued, “Through such practices, Allied has presented to the public a completely inaccurate view of the strength of the company and its investment portfolio. This fraud allows Allied to grow continually—as its most recent stock offerings demonstrate.” Since my speech in May 2002, Allied had raised about $470 million from issuing roughly 22 million shares, or 20 percent of the company.

I concluded the letter by urging the SEC to be more aggressive toward Allied: “Allowing Allied to persist in this behavior is fundamentally unfair both to investors and to competing investment companies that keep honest books and fully disclose negative information concerning their investments. We request that you investigate Allied’s practices and take appropriate action promptly and publicly to correct Allied’s misleading disclosures and overstated financials.”

Then, like always, we waited. While we were waiting, Allied announced that BLX had a bad third quarter in terms of loan originations and profits. For the quarter, BLX’s origination volumes declined 21 percent and earnings before interest, taxes and management fees fell 53 percent to only $6 million, compared to $12.9 million the previous year. On the conference call announcing the results on October 28, 2003, Allied management began by trumpeting that BLX obtained PLP status from the SBA in all markets, including Puerto Rico and Guam, before explaining that, to improve its securitization execution, it needed to diversify its industry concentration. It appears BLX’s loans were too concentrated in gas stations and motels. This “strategic shift” to reduce the overconcentrations caused the decline in origination volumes and profits. Management thought the problem would persist as the “diversification efforts will take some time.” Notwithstanding this obvious bad news that the company admitted would persist for a while, Allied further expanded the enterprise valuation of BLX from $465 million to $476 million.

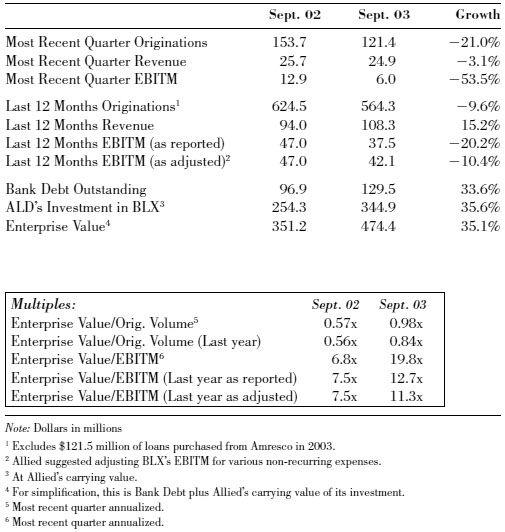

These were important numbers. As discussed in Chapter 12, Allied’s initial description of how it valued BLX was absurd. Now, with Allied’s announcement of the enterprise value, we could compare that old valuation of BLX to this new, even more fanciful one.

As

Table 20.2

on page 190 shows, originations and operating profit before management fees (EBITM) had fallen over a full year. BLX incurred more bank debt. Even so, Allied dramatically increased the valuation of its own investment. The valuation multiples, which we believed to be unreasonable a year earlier, expanded dramatically. Allied’s expansion of BLX’s multiples, even as the results deteriorated, reached absurdity.

Table 20.2

BLX Valuation Comparison

We were also able to follow the circular money trail between Allied and BLX. Allied recognized more in fees, interest, and dividends than BLX generated in EBITM, none of which was cash. We pieced together all the SEC filings and found that BLX burned through $32 million in cash before paying Allied anything the previous year. BLX borrowed this money from its credit line, which Allied co-signed. BLX then “paid” Allied $39 million in interest, fees, and dividends. That money showed up on Allied’s books as income, boosting its earnings per share. Allied used it to pay its distribution. At the same time, Allied invested an additional $39 million in BLX. It was a spinning circle of money.