Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation (4 page)

Read Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation Online

Authors: Elissa Stein,Susan Kim

Tags: #Health; Fitness & Dieting, #Women's Health, #General, #History, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #Personal Health, #Social History, #Women in History, #Professional & Technical, #Medical eBooks, #Basic Science, #Physiology

WHERE WE ARE TO DAY

S

O HERE’S A PROPOSAL FOR YOU.

What if you could determine when, how much, and how often, if ever, you’d menstruate for the rest of your reproductive life? What if you could turn your flow off, not unlike a faucet, and then rev it back up again if, say, you ever wanted to get pregnant?

Sounds too good to be true? Well, pinch yourself, sister—your dream is now a reality, thanks to your pharmaceutical pals at Wyeth, Barr, Organon USA, Watson, Warner Chilcott, and Berlex Inc.!

“Menstrual suppression” is currently hovering like a multimillion-dollar question mark above our collective head, while countless scientists, advertisers, drug executives, gynecologists, femcare manufacturers, and shareholders wait breathlessly to hear how we’re going to respond. It turns out that here in the twenty-first century, we seem to be poised on the threshold of a Brave New World when it comes to menstruation. The process itself is being chemically redefined in strange new ways, with all kinds of giddy promises being made and tantalizing possibilities dangled in front of our collective nose.

No more periods!

Who wouldn’t be overjoyed, we’re told by ads and articles that we’re sure will only increase in number and shrillness as time goes by. What woman wouldn’t love bidding adieu to all that mess, the cramps, the bloating? Who wouldn’t want to get rid of the supplies, the black “just in case” pants with the stretchy waistband, the stained sheets and underwear, the painful breasts, the psychomeltdown PMS, the backaches? Why, no right-thinking woman alive, that’s who! We’re the lucky ones who get to live in an era when we can effortlessly pole-vault over our physical limitations to thrilling new heights of ease, comfort, and freedom. What kind of Neanderthal would knowingly choose to remain bound by her biology, imprisoned by the unthinking cycles of her animal self, stuck in an “imperfect” body?

Sounds like the answer is pretty obvious, right? And yet, we hesitate.

Don’t get us wrong. We truly do appreciate that plenty of women flat-out hate their periods, and with ample reason. To them, menstruation is no friendly, gentle nuisance but a seriously painful, horribly messy, even health-threatening monthly event: a genuine curse. Even as women who don’t have such negative feelings about our periods and are actually on pretty good terms with the whole process, we can certainly understand the appeal. If we can change the shape of our noses, vacuum fatty tissue from our buttocks, get a new kidney when one fails, correct blurry vision with lasers, fight killer infections with antibiotics, and have kids even if we’re technically sterile … why shouldn’t we be able to control our flow?

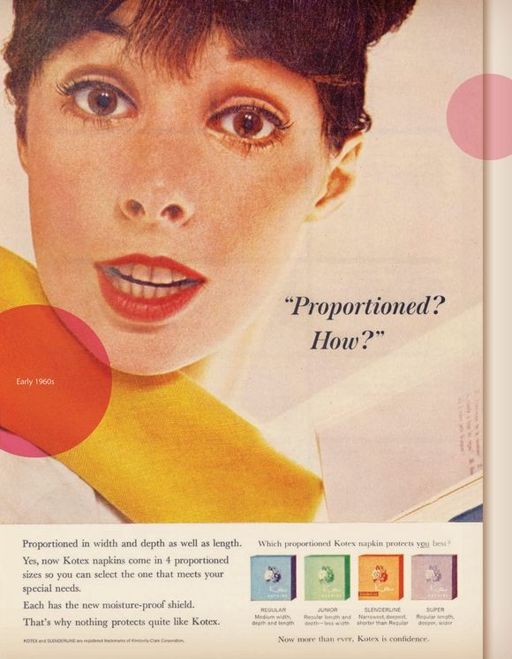

How many improvements can one make to a pad

,

anyway?

As far as we’re concerned, part of our hearts leap at the glad thought of never again having to hand-scrub our underwear in cold water or beg another quarter off a stranger in a restroom just to buy an emergency tampon. And yet not to be wet blankets, when we consider the possibility of menstrual suppression, we are left more than a little confused, as well as downright concerned.

What disturbs us right off the bat is the one-size-fits-all assumption such a pitch is based on, since all of us have significantly different feelings about our periods. That which is unbearable to one woman is ho-hum and matter-of-fact to another; one woman’s horrible monthly ordeal is another’s womanly goddess ritual, and a vaguely irritating reassurance (I’m not pregnant!) to yet another.

Nevertheless, here we are, all being indoctrinated with the same line: that menstruation is so awful, of course we all want to get rid of it. What bothers us most is that the motives underlying this message are as suspect as they ever were, arising as they do not from hard science, long-term studies, or even from our actual needs or wants, but from the tender feelings of company shareholders.

So how did this all come about?

First, let’s keep in mind that commercially produced femcare—pads, belts, tampons—has been around for only a hundred years or so. Since their launch, there have been noticeable improvements that we, for the most part, applaud madly. Who doesn’t prefer that today’s superabsorbent pads are wafer-thin, meaning that one no longer has to waddle around with the Manhattan Yellow Pages stuffed between her legs? Or that there’s such a variety of tampon styles, sizes, and applicators, even a first-timer twelve-year-old can generally find something she can insert without the need for heavy sedatives?

And yet, even the most sanguine of businessmen realized long ago that there’s ultimately a limit to what kinds of products can actually be made and sold to women when it comes to sopping up a few spoonfuls of blood every month. How many improvements can one make to a pad, anyway? If there’s anything you can figure out about making a pad, say, even more absorbent, with even better wings, or perhaps an even prettier tampon with a glide-ier applicator, you can rest assured there are many teams of scientists feverishly working on it this very second. Yet dealing with the actual effluent of menstruation is just the tip of the revenue iceberg. Sure, there’s money to be made from pads and tampons; but there’s potentially huge money, monster dollars, to be harvested from tinkering with the actual process itself—something the medical community and pharmaceutical giants figured out years ago.

This all came about in large part due to one of the hottest trends that has sprung up over the past half century, one that sociologists in the 1970s dubbed “medicalization.” Medicalization occurs when health or behavior conditions that have traditionally been thought of as being part of normal life are redefined by experts as actually being medical in nature—thus requiring medical solutions (e.g., drugs, surgery, hospitalization), as opposed to environmental, social, or even practical ones (e.g., a better diet, a raise in one’s salary, more exercise, a full-time maid/cook/masseuse).

We’re now experiencing a seismic marketing shift toward so-called preventive and quality-of-life drugs—medicines that treat an underlying condition. Invariably, the conditions are items on that vaguely dispiriting, seemingly endless list of what it means to be alive: sexual dysfunction, hay fever, obesity, bone thinning, restless leg syndrome, acid indigestion, even attention deficit disorder, depression, and anxiety. And yet all of these conditions have been systematically identified by the big pharmaceutical companies, who then developed the appropriate products, analyzed the proper markets, and pitched us, the lucky consumers. As a result, untold millions of dollars are now being made worldwide by treating conditions that weren’t even identified as such for most of human history.

The catch is, medicalization is a complex subject that can’t be solved by the simple equation “Drugs are bad, so just say no.” We ourselves are not Luddites who are so antitechnology, we’re still pushing mustard baths, mineral water purges, and homeopathic cures for serious underlying conditions. Nevertheless, what you don’t know about the way pharmaceutical companies develop blockbuster drugs might give you serious pause.

If you were a giant company looking to make some major scratch by inventing a new drug, where would you start? First, you’d definitely steer clear of developing the cure to some weird disease (because not enough people contract it) or short-lived infections (because they don’t last very long). No sir, in order for a drug to be insanely profitable, the potential market should be as big as possible … for example, “all women” is considered an excellent place to start. Furthermore, the ideal condition is something that, while annoying or even frightening, isn’t going to progress so fast that it’s going to kill anyone soon; it will hopefully linger on for years, ensuring a steady base of customers regularly holding aloft their prescription refills.

What fits the medicalization bill better than menstruation?

Patent and over-the-counter drugs to treat cramps and bloating have been around forever. Who doesn’t remember covertly cadging a Midol off a girlfriend injunior high like it was contraband? Primarily made up of acetaminophen with a little caffeine and some antihistamines thrown in, Midol was heady stuff when we were teens. Today, of course, there are drugs out there that make Midol seem like a handful of jellybeans: Seasonale, Seaso-nique, Lybrel, Implanon,Yaz. Sounding like the lineup on some female sports team from outer space, these pills promise to reduce or even halt one’s periods altogether for as long as one wants.

“But how can this be? you may be exclaiming, falling to your knees from the sheer wonder of it all.”What sort of miraculous new drug are you talking about?” In fact, it’s the same old wonder drug millions of us have already been taking for years and the single most common form of birth control here in the United States, constituting a $1.7 billion annual market. In short, menstruation suppressants are nothing more than birth control pills in a new package.

Regular birth control pills work in two ways: by thickening cervical mucus (which effectively prevents access to any eager-beaver sperm looking to hook up with an egg) and by flooding one’s hapless body with synthetic hormones, effectively tricking it into thinking it’s pregnant. As a result, ovulation ceases and the uterus stops building up its usual, heavy-duty layer of tissue, blood, and mucus.

Yaz, Bayer Health Care Pharmaceuticals

“The Pill” actually consists of twenty-one active pills and a fourth week of placebos. When you take the placebos, the endometrium (which, due to the low-dose stream of synthetic hormones, has built itself up in a very half-assed way) breaks down and flows out. Once you start back up on the active pills, the uterus again builds up a fresh, skimpy lining. This explains why one’s periods are not only light but incredibly regular when one is on the Pill. Everything is dictated by that precision flow of synthetic hormones.

One reason for building in this “pseudo-period” was that some pathologists were already worrying about the possible effects of a nonstop regimen of hormones. Another reason was that doctors felt that no period at all would be considered too freakish for most women to handle, and given what we know about 1960, the year the Pill came out, we think they were probably right. If you didn’t perm your hair, wear a girdle, or go to bed with a fresh coat of lipstick, that practically made you a bongo-playing beatnik. What would anyone have made of menstrual suppression?