Flight of the Eagle: The Grand Strategies That Brought America From Colonial Dependence to World Leadership (96 page)

Authors: Conrad Black

BOOK: Flight of the Eagle: The Grand Strategies That Brought America From Colonial Dependence to World Leadership

6.3Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

6. THE FORMOSA STRAIT AND VIETNAM

On September 3, 1954, the latest Chinese initiative to aggravate the United States and roil the waters in the Far East, devised with almost fiendish imagination, began. China started shelling the tiny offshore islands of Quemoy and Matsu, which instantly became household words throughout the world. The nearest of the islands is closer to the Chinese mainland than Staten Island is to Manhattan. They are rock piles, historically attached to China, that Chiang had stuffed with soldiers and used as jumping-off points for the harassment of Chinese coastal shipping, and for raids on the mainland. Chiang claimed that the fall of Quemoy and Matsu would severely compromise the security of Taiwan itself, and the Joint Chiefs disagreed with that assessment, but averred that they could not be defended without American assistance. This was complicated by the fact that the waters among and between the islands and China, at their narrowest points, were not accessible to the principal ships of the U.S. Seventh Fleet, because of the deep drafts of its heavy units, in particular the giant aircraft carrier

Midway

.

Midway

.

Admiral Radford and his colleagues on the Joint Chiefs visited the president in Denver on his summer holiday on September 12 and for the third time in less than six months recommended the use of atomic weapons on China, and also the deployment of American forces on the islands. Eisenhower wouldn’t hear of it; he said that if war broke out, Russia, not China, would be the main counter target, and he lectured them forcefully on the requirements of constitutional government and the need to obtain congressional approval for the use of such weapons, especially in so abstruse a cause. The implications of the fact that the Chiefs, the successors of MacArthur, Marshall, Eisenhower, Nimitz, and Bradley, would be so relaxed about precipitating millions of people into eternity for such nonsensical strategic assets are disquieting. Roosevelt would have had the self-confidence, and Truman the gritty independent-mindedness and Missouri skepticism, to refuse them; but even better was Eisenhower’s dismissal of Radford’s requests as military, moral, strategic, and constitutional foolishness. Senior military officials can always impute the non-cooperation of civilian chiefs to their strategic philistinism and civilian squeamishness; this is much more challenging with a president who reached the highest possible rank in the combat U.S. Army, successfully commanded the greatest military operation in world history, and received the unconditional surrender of the nation’s enemies in Western Europe.

The usual suspects fell for Chiang’s response to Mao and Chou’s tweak. Senator Knowland demanded a naval blockade of the whole Chinese coast. To the shouts of Knowland and McCarthy and their claque about the “honor of America,” Eisenhower replied that he was well familiar with that honor and did not construe it as being “insensible to the safety of [American] soldiers.”

163

In December, he signed a mutual-defense treaty with the Nationalist Chinese that made an attack on either an attack on both, but confined the definition of Nationalist China to Taiwan and the Pescadores. Chiang agreed formally not to initiate hostilities with the People’s Republic unilaterally, conforming with the message Nixon had been sent to deliver to Chiang and Syngman Rhee the year before. The Chinese bombardment of Quemoy and Matsu continued for the rest of 1954, steadily intensifying, and there were repeated requests from Chiang, the Republican right, and the JCS to take drastic action. Eisenhower privately recommended against Chiang putting “more and more men on those small and exposed islands.”

164

At a news conference in late November, Eisenhower answered a question about using military intervention in response to Chinese mistreatment of American POWs in Korea by saying that he had written “letters of condolence ... by the thousands, to bereaved mothers and wives. That is a very sobering experience.... Don’t go to war in response to emotions of anger and resentment; do it prayerfully.”

165

163

In December, he signed a mutual-defense treaty with the Nationalist Chinese that made an attack on either an attack on both, but confined the definition of Nationalist China to Taiwan and the Pescadores. Chiang agreed formally not to initiate hostilities with the People’s Republic unilaterally, conforming with the message Nixon had been sent to deliver to Chiang and Syngman Rhee the year before. The Chinese bombardment of Quemoy and Matsu continued for the rest of 1954, steadily intensifying, and there were repeated requests from Chiang, the Republican right, and the JCS to take drastic action. Eisenhower privately recommended against Chiang putting “more and more men on those small and exposed islands.”

164

At a news conference in late November, Eisenhower answered a question about using military intervention in response to Chinese mistreatment of American POWs in Korea by saying that he had written “letters of condolence ... by the thousands, to bereaved mothers and wives. That is a very sobering experience.... Don’t go to war in response to emotions of anger and resentment; do it prayerfully.”

165

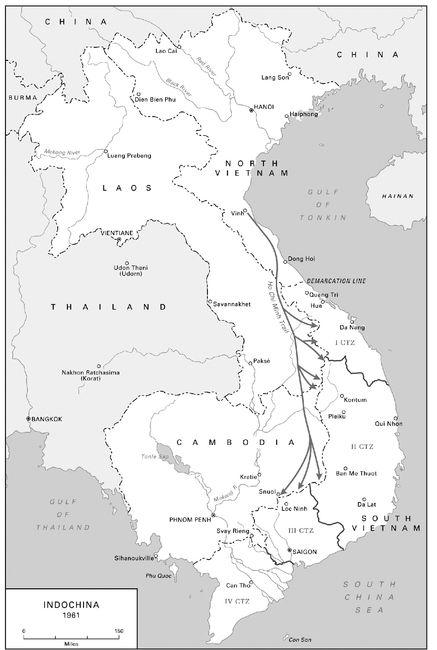

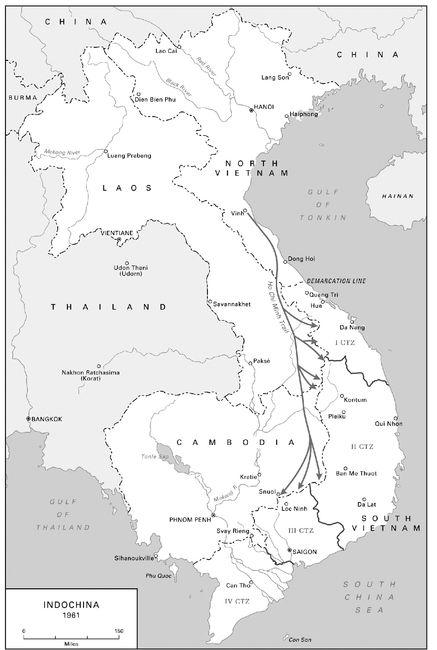

Vietnam War. Courtesy of the U.S. Army Center of Military History

Five times in the course of 1954 he had been asked by military and State Department advisers and congressional supporters to go to war in Asia, usually with a sprinkling of atomic bombs upon China: in April and again in May as the Dien Bien Phu surrender approached, in late June when the French claimed the Chinese air force was about to attack them, in September at the beginning of the shelling of Quemoy and Matsu, and again in November when China revealed the conditions in which it detained captured American airmen.

The ink (none of it American) was scarcely dry on the Geneva Accord when problems began to bubble up from the nascent but unproclaimed state of South Vietnam. Allen Dulles had sent the astute intelligence colonel Edward Lansdale (model for the good official in the novel

The Ugly American

) to harass the Viet Minh and assess Diem in the autumn of 1954. Lansdale reported that the Viet Minh were going to take absolute control of the North very quickly, and that Diem’s efforts to install himself were proceeding with difficulty, and in November Eisenhower appointed the distinguished combat general J. Lawton Collins as ambassador to what the president called “Free Vietnam.” Collins was given command over the entire American mission in the new country and the mission statement to assist in building and preserving its sovereignty. Lansdale had warned that when it became clear that the elections Chou and Mendès-France had set up at Geneva, to be held after the two-year decent interval to save a little decorum for France did not occur, Diem would have an insurrection, and to the extent that North and South Vietnam were separate countries, a war, on his hands.

The Ugly American

) to harass the Viet Minh and assess Diem in the autumn of 1954. Lansdale reported that the Viet Minh were going to take absolute control of the North very quickly, and that Diem’s efforts to install himself were proceeding with difficulty, and in November Eisenhower appointed the distinguished combat general J. Lawton Collins as ambassador to what the president called “Free Vietnam.” Collins was given command over the entire American mission in the new country and the mission statement to assist in building and preserving its sovereignty. Lansdale had warned that when it became clear that the elections Chou and Mendès-France had set up at Geneva, to be held after the two-year decent interval to save a little decorum for France did not occur, Diem would have an insurrection, and to the extent that North and South Vietnam were separate countries, a war, on his hands.

For Eisenhower to approve the cancellation of the elections, and send a four-star general to Saigon with a clear mandate to reinforce the permanent independence of South Vietnam and help it build an army and fight the war that Collins warned was about to begin again, was a very serious step into what would prove a tragic adventure. Eisenhower met with Collins on November 3, just before his departure for Saigon, and told him that he wished to emulate the examples of Greece and South Korea and assist the South Vietnamese to be able to defend themselves. Eisenhower had complained that the French, after his old comrade de Lattre de Tassigny died in 1951, wanted American aid but would not listen to American advice. He transferred a $400 million package of military assistance to France to South Vietnam, and told Collins to disperse it according to his best judgment (and Collins was as distinguished a general as de Lattre, and infinitely more so than Salan). Many questions remain over these decisions, especially if, despite all the business about dominoes, Eisenhower would not have been better off to keep his hands off South Vietnam and announce that the French had fumbled away all Indochina and that the dominoes started at Malaya, Thailand, and other sturdier and more coherent states; and if he was going to take a stand, if he could not have taken it while France was still a factor in Indochina, trading evacuation from Dien Bien Phu and even the insertion of some forces, in exchange for a durable French military commitment to the newly independent non-communist Indochinese countries.

Eisenhower sent Dulles to Europe in September 1954 to arrange Germany’s election to NATO. He agreed with West German chancellor Konrad Adenauer that the German army would not exceed 12 divisions, that West Germany would not seek nuclear weapons, and that control would reside with the NATO commander (SACEUR, the post Eisenhower had set up). Dulles carried out his mission skillfully, and the threat remained, if France did not come on side, that the United States would finally make a bipartite arrangement with West Germany. The French National Assembly and the U.S. Senate ratified the arrangements, and the integration of the Federal Republic of Germany into the Western Alliance in April 1955 was one of the greatest of Dwight D. Eisenhower’s many historic achievements, as military commander and as president.

The French, in one year, had managed their greatest military defeat—apart from 1940 and Bismarck’s capture of Napoleon III at Sedan in 1870—since Waterloo, if not Napoleon’s defeat in Russia in 1812, and had fumbled their way into secondary position as a continental European ally behind Germany, the mortal and genocidal enemy of less than a decade before. Eisenhower bore in mind at all times that Europe was the key theater and Cold War battleground, and that too aggressive or impetuous a policy in the Far East would spook America’s allies in Western Europe, where communism was militating within a hundred miles of the Rhine in East Germany, and seething and fermenting in more than 20 percent of the population in France and in Italy. America and the Western world were well-served by his world view, as they were by the U.S. president’s disposition to discount the alarms and bellicosity of his Joint Chiefs.

In the off-year election in November 1954, the Republicans lost control of both houses of the Congress fairly narrowly, and Sam Rayburn and Lyndon Johnson began the exercise of an iron control over the House and Senate that would continue to the end of the decade. They were two of the legendarily capable leaders in the history of the Congress, on a par with Clay and Webster (as managers not orators). Eisenhower gained general bipartisan support, apart from the more extreme members of the reactionary Republican right, for his strategic policy of containment in Europe through American-led alliance, the arming of infiltrated countries (building on the Truman Doctrine), a reduction of American military manpower, and a steady build-up of air, naval, and atomic superiority, while prompting counter-subversion through the CIA wherever a country was threatened and seemed susceptible. This was the “New Look,” which many senior officers and some Republican hawks criticized, but which preserved the peace and avoided large deficits and tax increases.

New Year’s Day, 1955, was an occasion for mutual threats of war from Chou En-lai and Chiang Kai-shek. The Communists seized a couple of the small islands in the Formosa Strait. Eisenhower broke new constitutional ground in asking Congress for authority to use any level of force, including atomic weapons, that he judged necessary, for the defense of Formosa and the Pescadores, and “closely related localities,” the identification of which would be left to the president. Eisenhower produced the “Formosa Doctrine,” which like many of his forays into the prosaic, especially at press conferences, was designed to be incomprehensible: Chou called it a war message and Chiang complained that it did not cover Quemoy and Matsu. Eisenhower made it clear to the Joint Chiefs and the congressional leaders that he would only use the degree of force he thought necessary to defend Formosa and the Pescadores, and that on no account would he allow an attack upon mainland China or be dragged into the Chinese Civil War by Chiang. The timeless leaders of the House, Speaker Sam Rayburn and minority leader and former Speaker Joe Martin, jammed it through without debate, 403–3. There was a resolution in the Senate curtailing Eisenhower’s authority, but this was brushed aside and Johnson and Knowland put the president’s measure through after three days, 83–3. Eisenhower, in a remarkable vote of confidence, was given a blank check, even to blast China with atomic weapons if he thought the national interest justified it.

In almost identical letters to the NATO commander, General Alfred Gruenther, and to Winston Churchill (who was finally about to retire as prime minister, after nine years and over 30 years in government and 54 years in Parliament), Eisenhower wrote that Europeans consider America “reckless, impulsive, and immature,” but reminded them that he had to deal with “the truculent and the timid, the jingoists and the pacifists.” Where Roosevelt flattered whom he had to, dissembled when he felt it necessary, and sailed through like a monarch, and Truman took the best decision as each came up, crisply and clearly, Eisenhower was always mindful of the political landscape and maneuvered in a grey zone of complicated syntax and personal discretion, aware of the poles between which he had to operate.

Churchill was skeptical about anything to do with East Asia, and really cared only about Hong Kong and Malaya. He didn’t believe the version of the domino theory that Eisenhower tried to sell through a visit by Dulles—a rather pious, overserious, and uncongenial man to send as an emissary to Churchill, unlike Acheson, who liked a drink and was very witty and much more articulate than Dulles. Churchill and Eden didn’t buy any of it, and thought the U.S. should try to negotiate the handover of Quemoy and Matsu for a guarantee not to bother Formosa, which, as Eisenhower said, was “more wishful than realistic.” In post-colonial terms, the British had no idea at all of how to deal with East Asia, and had no resources to be a factor there anymore.

Dulles went from London to the Far East and said when he returned to Washington that he doubted the Nationalist Chinese army would remain loyal to Chiang if the Communists invaded, and that if it was the president’s decision to defend Quemoy and Matsu, atomic weapons would have to be used. There was a great deal of concern, even among conservative Democrats like Johnson, about betting too much on strategic rubbish like Quemoy and Matsu. Truman’s favorite general, Matthew B. Ridgway, now the chief of staff of the army, told congressional hearings that he opposed Eisenhower’s “New Look” of fewer troops and more firepower, atomic and otherwise. Eisenhower was sorely tempted to sack him, as Truman had fired MacArthur, but didn’t, partly on the advice of Dulles.

Other books

Searching for Tomorrow (Tomorrows) by Mac, Katie, Crane, Kathryn McNeill

Killjoy by Julie Garwood

Why Pick on Me by Louis Sachar

Stray Souls (Magicals Anonymous) by Kate Griffin

Consume: A Standalone Romance by Lauren Hunt

The Summer House by Moore, Lee

Finder: First Ordinance, Book One by Connie Suttle

Adiós, Hemingway by Leonardo Padura

Truffled to Death (A Chocolate Covered Mystery) by Kathy Aarons

Unforgiven (A Cyn and Raphael Novella Book 3) by Reynolds, D. B.