Flight of the Eagle: The Grand Strategies That Brought America From Colonial Dependence to World Leadership (55 page)

Authors: Conrad Black

BOOK: Flight of the Eagle: The Grand Strategies That Brought America From Colonial Dependence to World Leadership

5.6Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Considerable interest had arisen over the precise line of the boundary between the Alaska Panhandle and the Canadian province of British Columbia after the Klondike gold rush of 1896. Canada invoked the Anglo-Russian Treaty of 1825, which set the border at the outer edges of the peaks of the Rockies, while the United States invoked a line between the heads of bays and inlets along the coast. That would assure U.S. retention of the harbors. In January 1903, the U.S. and Great Britain signed an agreement confiding the determination to a joint commission consisting of three Americans, two Canadians, and the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, Lord Alverstone. Alverstone cast his vote with the Americans, and the matter, which had never been more than an irritant, was settled in America’s favor, to the annoyance of the Canadians, who felt they had been put over the side by the mother country, but accepted that the higher interests of empire could not accommodate trivial disputes with the United States.

By this time, the United States had become such an immense power in the world, and was led by such a dynamic and aggressive president, and Britain was in such an intense contest of naval construction with Germany, that the British national and imperial interest required almost open-ended deference to the United States. France and Russia were in alliance against Germany and Austria-Hungary (Hungary having acquired parity with Austria, largely through the cunning political infighting, accompanied by extraordinary skills in the Habsburg salons and boudoirs, of the dashing and formidable Hungarian premier and foreign minister, Count Andrássy, with the help of Bismarck). Italy was loosely attached to the Berlin-Vienna alliance, and the Entente Cordiale between France and Britain was growing steadily more intimate, ancient foes now reconciled in the shadow of German military and naval might, with Alsace-Lorraine part of the German Empire and the German navy laying keels of ever larger battleships almost as swiftly as the British. The impetuous young Emperor Wilhelm II, after dismissing Bismarck as chancellor, had allowed the alliance with Russia and the isolation of France to lapse, as he became embroiled in the Habsburg-Romanov contest for the South Slavs and gratuitously challenged Britain’s supremacy on the seas, the one concern that could always be relied upon to drive Britain into the camp of a rival’s enemies.

Roosevelt himself was the first American president since John Quincy Adams (though Buchanan almost qualified) who had traveled extensively in Europe and had a sense of America’s relations to Europe. In his early twenties he had written the definitive history of the naval campaigns of the War of 1812, and he and Admiral Mahan were among the six authors of the official history of the Royal Navy, because of their undoubted scholarship in the field. Mahan had been an indifferent sea commander, but when tapped for the Naval War College at Newport in 1866, intensified his studies and began his exposition of the strategic importance of sea power by illustrating the Roman advantage over the Carthaginians in the Punic Wars: Rome could transport its forces by sea while Carthage had to cross North Africa to the west from what is Tunisia and then cross to Spain and approach Italy through Spain and France. His

Influence of Sea Power on History, 1660–1783

(

see

pp. 273–274), published in 1890, strategically explained the rise of Britain.

Influence of Sea Power on History, 1660–1783

(

see

pp. 273–274), published in 1890, strategically explained the rise of Britain.

These men provided a serious and academically learned basis for American strategic policy and supported an international presence for America far exceeding the confines of the New World. Mahan presciently pointed out that the Philippines could not be defended against a militarist Japan, and an informal understanding was made between Roosevelt and the Japanese that the American occupation of the Philippines and the aggressive Japanese occupation of Korea and Formosa would be reciprocally tolerated (the Taft-Katsura Agreement of 1905). Roosevelt strenuously accelerated U.S. naval construction, which only enhanced the United States’s position as holder of the key to the world balance of power, a position Britain had largely vacated by entering into alliance with France and Russia against Germany and its allies. Less than a century after Britain had successfully assisted, exhorted, and bankrolled the Prussians, Russians, Austrians, Spanish, and Swedes against Napoleonic France, ending French hegemony in Europe, Britain’s weight, committed entirely to the assistance of France and Russia, might not be sufficient to counter and deter the great power of Germanic Europe, Bismarck having undone the work of Richelieu, Germany’s great fragmentor, and reconstructed a Teutonic power in Central Europe of immense strength and uncertain benignity.

The rise of Germany to parity with Britain and the comparative decline of France, punctuated by decisive defeats by Pitt in Canada, Wellington on the French frontier, and Bismarck at the gates of Paris, left the nascent and mighty industrial and demographic and still almost revolutionary republican force of America as the arbiter of the fates of nations and alliances in the Old World, on the opposite sides of both major oceans. To proclaim America’s new vocation, Theodore Roosevelt sent the main American battle fleet, painted white and popularly known as The Great White Fleet, on a goodwill mission around the world in the last year of his presidency. It was admirably within the U.S. tradition of astute public relations, being much noticed in the world, and it fired the imagination of many Americans who had not been in the habit of thinking much beyond their own sea-girt borders.

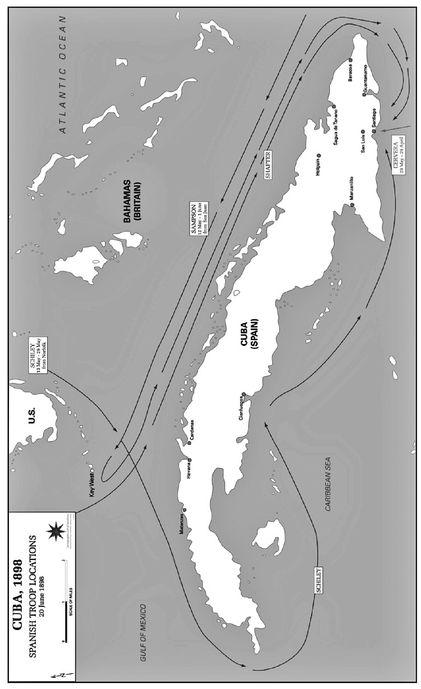

Cuba in the Spanish-American War. Courtesy of the Department of History, United States Military Academy

Roosevelt, unlike his predecessors since Lincoln (with the partial exception of Grant, whose strategic perceptions were famously acute and well-known but hadn’t been much applied outside the United States), saw, relished, and exploited these changes. He had been a puny youth who had overcompensated by making himself, from sheer willpower, a barrel-chested rancher, frontiersman, and roustabout in the badlands, as well as a big-game hunter, and was an academic whose treatment of historic and strategic subjects achieved renown well beyond the British acceptance of the fairness and perception of his account of the naval operations in the War of 1812. His compulsive bellicosity has been mentioned in the Venezuelan–British Guyana border dispute. As New York City police commissioner, he was given to arbitrary round-ups of people out for a stroll late at night, on the grounds of aggressive suspicion. He was always quick to anger and more prone even than Jackson to escalate personal quarrels to feuds and fights to the death, and national disagreements to war.

He was a flamboyant campaign orator, referring to Bryan as a “human trombone.” And he had almost superhuman energy, with mixed results. On one occasion, while he was giving a speech, he was the subject of an assassination attempt, but the bullet was largely absorbed by a book in his breast pocket and did penetrate his chest. There was a commotion as the gunman was subdued, and Roosevelt finished the speech. And once he became so enthused chopping trees that he chopped down those to which the telegraph lines to his house were attached, rendering him incommunicado as he awaited an important message. He had, in the French expression, the fault of his qualities. But with his bullying and simplistic aggressivity, there coexisted a high and well-informed intellect and a very strong sense of the national destiny, benign global mission, and the unsulliable honor of America. He was a brave and intelligent man, and also a very belligerent and impulsive one. The office, as well as the times and the voters, appeared to have sought the statesman.

In domestic affairs, Roosevelt’s principal initiative in his first years as president was to assert the power of the federal government over the monopolies that had arisen in many of the country’s industries. Failing to gain Senate approval of a policy to curb the trusts, as they were known, he ordered the attorney general, Philander C. Knox, to prosecute and seek the dissolution of Northern Securities, a railway holding company assembled by the epochal financier J. Pierpont Morgan. In August and September 1902, Roosevelt conducted a whistle-stop railway tour of New England and the Midwest whipping up public support of his policy, which he clearly defined as friendly to private enterprise, but not to monopolistic threats to the public interest. He benefited from the intractable position of the coal mine owners during the anthracite coal strike of 1902, and in 1904 the Supreme Court of the United States approved the administration’s prosecution of Northern Securities. Roosevelt strengthened this policy with enabling legislation, including the Expedition and Elkins Acts, and artfully presented his policy as “a Square Deal” for the country.

The Republicans met in Chicago in June 1904, and President Roosevelt was nominated by acclamation, with Indiana Senator Charles W. Fairbanks, an orthodox McKinley conservative, for vice president. The Democrats met in St. Louis in July, and were in a demoralized state in the face of Roosevelt’s immense popularity. They could not face a third straight nomination of Bryan, and Cleveland, the nominee for the previous three elections, had retired. Cleveland and other gold-standard Democrats from New York successfully put forward the candidacy of the chief justice of the New York Court of Appeals, Alton B. Parker, who chose the 80-year-old Henry Gassaway Davis, the oldest major party nominee to national office in American history, a former senator and millionaire coal mine owner from Virginia, for vice president. It was a gold-standard platform, which alienated the Bryanites and echoed Roosevelt’s views on the trusts, but was almost silent about Roosevelt’s assertive foreign policy. It was a tired and nondescript pair of nominees to challenge such a forceful and refreshing and successful incumbent. The Socialists ran Eugene Debs again, and the Prohibitionists, with unintended irony, a Silas C. Swallow.

There was never the slightest doubt of the outcome, and on election day Roosevelt won, 7.63 million to 5.1 million for Parker, 412,000 for Debs, 259,000 for Swallow; 56 percent to 38 percent to 6 percent for the lesser parties. The electoral vote was 336 to 140, as Roosevelt took every state outside the old Confederacy. On election night, Roosevelt gave the ill-considered and fateful promise not to seek renomination. He was the fifth president to inherit the office in midterm through the death of the incumbent, but the first to be reelected in his own right (unlike Tyler, Fillmore, Andrew Johnson, and Arthur, of whom all but Johnson sought renomination unsuccessfully), a pattern that would now be followed in the next three such cases (Coolidge, Truman, and Lyndon Johnson). It was the most one-sided U.S. presidential election victory since James Monroe ran for reelection without organized opposition in 1820.

6. ROOSEVELT’S SECOND TERMJohn Milton Hay, one of America’s most capable secretaries of state, died on July 1, 1905. He was an urbane and witty man, and got on well with Roosevelt. The distinguished jurist, and McKinley’s and Roosevelt’s war secretary, Elihu Root, succeeded him, and maintained the high standard set by Hay, though he was a reversion to the secretary with a legal rather than diplomatic background. Root had been succeeded as war secretary by William Howard Taft, who returned from a highly successful and imaginative term as governor of the Philippines.

War had broken out between Japan and Russia over spheres of influence in China, and especially Manchuria, and the Japanese had mauled the Russian fleet badly. Roosevelt opposed a lop-sided victory by either side, in order to assure the continuance of American preeminence in the far Pacific, and he expressed concern for the preservation of the Open Door policy in China. The Japanese requested and the Russians accepted his mediation in May and June 1905, and Roosevelt convened the peace conference at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in August. A treaty emerged after only a few weeks, securing Japan’s position in Korea and confirming its succession to most of Russia’s commercial and railway rights in Manchuria, giving Japan the southern half of Sakhalin Island, but denying Japan an indemnity from Russia. Roosevelt’s mediation role was executed knowledgeably and fairly, and he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1906. Roosevelt maintained good relations with both powers and reached a “gentlemen’s agreement” with Japan in 1907, in which Japan promised to withhold passports from migratory laborers bound for the U.S. This was Roosevelt’s response to a good deal of concern in the western states about “the Yellow Peril” represented by Oriental immigration. It was a genteel and civilized response to ugly racist agitation. The Root-Takahira Agreement of 1908 would formally confirm “the status quo” in the Pacific and uphold the Open Door policy in China but also that country’s independence and integrity. (Given the extent of foreign meddling in China, this was just a placebo.)

The next evidence of risen American influence and the aptitudes of its current president came in the Moroccan crisis of 1906. France had coveted Morocco for some time, to add to its colonial occupation of Algeria and Tunisia, and had negotiated British and Italian approval of its assumption of a protectorate status over Morocco. (Britain and France formally signed the Anglo-French Entente in 1904, one of history’s most important and successful alliances, in the furtherance of which even the king and emperor, Edward VII, had played a role, with a very successful state visit to Paris in 1903.) Germany was the chief opponent, and the German emperor, Wilhelm II, as was his wont, set himself up as the champion of Moroccan independence, as he had of Dutch Afrikaner independence in South Africa, a conflict that required Britain three years to win.

Other books

The Education of Mrs. Brimley by Donna MacMeans

How to Deceive a Duke by Lecia Cornwall

The Back-Up Plan by Mari Carr

Brownie and the Dame by C. L. Bevill

Julia London - [Scandalous 02] by Highland Scandal

The Song of Andiene by Blaisdell, Elisa

The Ambushers by Donald Hamilton

He Touches Me by Cynthia Sax

The Heretic Land by Tim Lebbon

Promise Me Forever by Lorraine Heath