Five Odd Honors (24 page)

Authors: Jane Lindskold

“Ox, Tiger, Snake, Horse, Ram, Monkey, Rooster, Dog . . .” Li said. “Dangerous names to bear in this Land at this time. When you are sniffed out, take care.”

“Does everyone here have your ability to sniff ?” Riprap asked.

“A good question from a Dog,” Li said approvingly. “No. Everyone does not, but then those who hunt you will not be everyone—only some rather dangerous people.”

“Who?” Copper Gong began, then she stopped herself with visible effort. “Please, Honored Li. What has happened? Some of us have been away from the Lands for many years, but from what we have been told, these changes are relatively new.”

“They are,” Li agreed. “Only a few months old, but that is long enough to feel as if they have lasted forever.”

He held up his cup. Wordlessly, Des refilled it.

“Let me see, how to begin?” Li said, shifting his crippled leg into a more comfortable position. “Perhaps with the fall of the last emperor to sit upon the Jade Petal Throne.

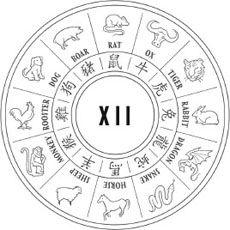

“As all of you . . .” Li glanced at Riprap and Des, then amended his words. “As most of you know, although the Lands consist of many and varied kingdoms, there is one kingdom that, especially in matters of magic, is considered the most important. This is the Jade Kingdom Under Heaven. The ruler who sits on the Jade Petal Throne is considered the greatest emperor of the Lands. He—or occasionally she—is advised by the human incarnations of the twelve signs of the zodiac, human embodiments of the Twelve Earthly Branches.

“In an ideal universe, this high emperor would be just and his advisors wise. In fact, this has rarely been the case. The right to sit upon the Jade Petal Throne is highly contested, and a catalog of dynasties that have ruled the Jade Kingdom Under Heaven reads like a mongrel’s pedigree.

“But those of us who reside in the Lands grew accustomed to this. Especially for the hsien, which human backside warmed the smooth, cold stone of the Jade Petal Throne hardly mattered. Dragons, ghosts, spirits, demons, and supernatural creatures of all sorts—including immortals such as myself and my seven associates—went about our long and interesting lives, aware of the changes of rulership as mortals are aware of changes in the weather—inconvenient at times, but rarely lasting long enough to make a notable difference.

“Something like a hundred years ago, the Lands began to change. The battles contesting the right to hold the Jade Petal Throne became more violent. Emperors hardly had time to be fit for their coronation robes before they were displaced and those robes became shrouds. I cannot say I paid much attention, but one of my associates, Ts’ao Kuo Chu, has some interest in law and related matters. He commented that the power of the twelve advisors and the Twelve Branches had been attenuated and stability thereby threatened.”

Loyal Wind exchanged glances with his associates. They knew perfectly well why this had happened, for when the twelve advisors had become the Twelve Exiles, they had arranged to maintain their connection to the Earthly Branches. They hadn’t known if this would weaken the Earthly Branches in the Lands, but they had known this was a possibility.

And we didn’t mind one bit,

Loyal Wind thought, trying to decide whether ornot he felt guilty about it.

We hoped that if there was weakening, that we might be able to return home—either by invitation or because we could exploit the link.

Judging from the ironic twinkle in Li’s shining eyes, he was perfectly aware of who his audience was, and that he was telling them a tale intimately connected to their own lives.

“Then,” Li said thoughtfully, “a short while ago, things went completely wrong. I was sitting with my associates in a pavilion on one of the Fortunate Isles. We have resided there for quite a long time, gotten it arranged to our satisfaction—you know, pavilions angled to catch the morning sun and the afternoon breezes, convenient streams in which to cool the wine. . . .”

He held out his cup and Des poured in a bit more wine. Loyal Wind saw the Rooster stare into the neck of the bottle and frown, heft it as if trying to surreptitiously judge how much it contained, then frown again.

Bet it’s nearly as full as when they started,

Loyal Wind thought.

Li of the Iron Crutch wouldn’t want to run out of wine while telling a good story.

Li sipped his wine, nodded thanks to Des, and went on.

“There was this sensation. . . . I don’t know how to describe it except that simultaneously I felt squeezed and shoved. A wind was blowing with terrible force, howling in my ears. Yet when I looked around me I noticed that nothing on the Fortunate Isles was affected. Not a blossom was dislodged from its tree. Those leaves that shifted did so as if beneath the pleasant caress of the lightest breeze.

“Maybe leaves and grass and flowers weren’t affected, but I certainly was being blown. If I wasn’t nearly bald already, I think the very hairs would have been blown from my head. A good thing my crutch is iron, otherwise it might have been swept from my grasp. I held on to my crutch as if it was an anchor. Then, blown and pushed and squeezed, I found myself shoved right off our chosen Fortunate Isle—or the island pulled out from under me.

“I went tumbling ass over tea kettle, and when at last I was no longer being squeezed and blown and pulled I came to a stop here. Or I should say, not here precisely, as in on this lakeshore, but in this changed world.”

Li of the Iron Crutch gestured around him, at a sky that was streaked lime and violet, at grass that was a nice shade of pale pink, at the waters of a lake that, very strangely in contrast, were a clear and lucid blue flecked with small whitecaps.

“How long ago was this?” Copper Gong asked.

“Time is not something I am accustomed to measuring, dear lady,” Li said, “having reached a portion of my life where I am blessedly without appointments. Moreover, it is difficult to measure here. The sun rises and sets, true, night follows day, or day night, but sometimes I’m not sure I can tell the difference.”

They all nodded. They’d noticed the phenomenon themselves. Had Des not equipped several of their number with mechanical timepieces and reminded them to keep these wound, they might have been in a similar predicament themselves.

Even so,

Loyal Wind thought,

I doubt if those watches are keeping accurate time. There was that night when the sky glowed indigo and the stars seemed so near that we could see their colors and hear them sing. Time seemed to move faster then.

“Well,” Copper Gong said resignedly, “it couldn’t hurt to ask. Do you have any idea what caused the storm that drove you from your island?”

“And have you re united with your associates?” Flying Claw asked anxiously.

Loyal Wind knew the young man was thinking of his own family and that of Righteous Drum and Honey Dream. Thus far, they had seen nothing of any human community.

“I do not have any idea what caused the storm,” Li said. “I do know that my associates and I were far from the only inhabitants of the Lands to be disrupted. I have met numerous hsien—lesser deities, immortals, creatures of land and sea—who report having encountered a similar storm. I have also located my associates.”

He smiled at Flying Claw, appreciating the young man’s concern. “Their tales are similar to mine. We have dispersed throughout these altered Lands, seeking our island home, but none of us has found it. We have found other islands, empty palaces, deserted gardens, statues, but our own beloved Fortunate Isles, where the Queen Mother of the West has held her tranquil reign, those have been swept beyond our reach—or perhaps we beyond them.”

Gentle Smoke asked the question Flying Claw was too polite to press. “Is there any place where there are settlements of mortals? We have been traveling for many days in various directions, and we have not seen even the smallest village.”

Li scrubbed at the lobe of one ear with a long finger.

“I have not seen any,” he admitted slowly, “but there is a feature of these changed Lands that you have not yet encountered.”

Whereas when the immortal had told of his own adventures he had seemed cheerful, even enthusiastic, now his expression grew serious and the words came slowly.

“Please, sir,” Riprap said. “Tell us about it.”

Li frowned. “If you move toward the Center, you will find a forest, a forest unlike any I have ever seen or heard described. It is lifeless. Beneath the feet is drab grey rock—featureless rock without grain or strata or pattern. The surfaceis neither smooth nor rough, but is so hard that each step on it jolts through one’s bones—at least if they are old bones like mine.

“From this grey soil grow trees made entirely of stone, wind-polished so that the browns and whites and greys and pale blues of the stone shine in the sun.

“Above this expanse of stone is sky, white sky ungraced by a single cloud. My understanding is that this forest is about two days deep if one crosses in a straight line—I did not do so, but I spoke to a hsien who did. And crossing in a straight line is difficult in a forest. The hsien to whom I spoke said it took her more like three days, and her feet were bruised from the passage.”

Li of the Iron Crutch fell silent. Again, Riprap prompted him.

“And on the farther side, closer to the Center?”

“There is a wall of water, water falling straight down from a sky that holds not a single cloud. The hsien to whom I spoke could not penetrate this wall. She tried, but in two steps she was nearly drowned.

“She was rescued by a dragon who had crossed the watery zone. The dragon said that the wall of water was as high as the sky and easily as wide as the stone forest. As the dragon swam through the water wall, although breathing underwater offered no challenge to one of his kind, the force of the falling water beat upon his frame ceaselessly, pummeling him to the marrow in his bones.”

Again Li paused. This time Loyal Wind himself prompted, “Honored Li, on the other side of the wall of water, what did the dragon find?”

“The dragon found a sea of fire, not molten lava but living flame, rising and falling as would waves of water. This sea was interrupted by little islands, coals of fire, each as large as a house.

“Heat billowed up from the coals, making the very air melt and rasp against the throat whenever one drew breath. The dragon went no farther, nor did the dragon find anyone who had dared cross that fiery sea. When the dragon had recovered a little of his strength—and he found this very difficult since these regions seemed singularly devoid of ch’i—the dragon retreated.”

“And found the hsien,” Flying Claw said, “and rescued her.”

“Yes,” Li said. “She was a little mountain spirit, very delicate, like a wisp of milkweed.”

“No humans lived in these places?” Flying Claw asked.

“Not that either the mountain spirit or the dragon saw,” Li of the Iron Crutch replied.

Flying Claw spoke as if thinking aloud. “And no people here, and this strange barrier between us and the Center—where the humans might be.”

“Are you thinking,” Riprap said, “what I think you’re thinking?”

“That we should try to cross the stone forest, then swim through the wall of water, go over the fire and learn what is beyond?” Flying Claw said. “I am. We have known from the start that it is likely we must reach the Center, for at the Center is the Jade Kingdom Under Heaven.”

“Yeah,” Riprap admitted. “That’s what I figured you were saying. Well, we’re not equipped for such a trip. We’re going to need to hit headquarters first.”

Li of the Iron Crutch smiled sagely at them. Despite the fact that, by Loyal Wind’s estimation, the immortal had now drunk at least enough wine to fill two bottles—if not three—of the size Des held, he seemed unimpaired beyond a certain rosy glow.

The immortal rose from the blanket, leaning against his iron crutch, and smiling benignly at them all.

“If you find our island,” he said, “could you return it? We rather miss it, you know. It has been our home for quite a long time.”

“By all means,” Flying Claw said solemnly. “Regaining our homes is what this is all about, isn’t it?”

Is it?

Loyal Wind thought as he readied himself to return to his horse form.

A bit of doggerel he’d heard Riprap recite one day came back to him, slightly altered.

Ours not to reason why. Ours just to do . . . then die.