Five Odd Honors (19 page)

Authors: Jane Lindskold

This chiao had been a particular friend of Righteous Drum in more peaceful days in the Lands, a research associate of sorts, one of those who had helped Righteous Drum and his original allies set the foundations for the bridge that had carried them from the Lands into the Land of the Burning.

Loyal Wind silently urged the others.

Hurry! Hurry! I have waited over a hundred years for this moment. Suddenly each breath is too long to wait. Why are you taking so long? The gate stands. Surely the four Guardians who created the gates would not have erred. Hurry!

His expression still troubled, Righteous Drum turned away from his conversation with the chiao and addressed the twenty people who waited.

“My friend assures me that the Ninth Gate will open. Further, he assures me that it has not been detected by our enemies.”

“Father,” Honey Dream said, “this is all good news. Why are you so troubled?”

“Chiao—

lung

in general—do not perceive the world quite as we do, therefore I cannot precisely say. My friend speaks of unrest within the bones of the earth itself, of disruptions within what is and what should be. I sought clarification, but all I could gather was that we should be extremely cautious. Something is very wrong.”

Pearl Bright, the studied tranquility of her features giving away that she, too, was impatient to have this final ordeal ended, said softly, “But we could have guessed as much from what we learned from our newest allies.” She inclined her head politely at Twentyseven-Ten, Thorn, and Shackles. “We saw things at the end of the Tiger’s Road that remain unexplained. Then, too, there was Yen-lo Wang’s peculiar cooperativeness, against all expectation. Here is one more confirmation.”

Des Lee shifted his shoulders within his ceremonial shenyi as if loosening them for action.

“Pearl’s right. Delaying won’t tell us anything. Let’s open the gate.”

Albert Yu glanced at Righteous Drum, and only when the Dragon nodded agreement did he move to the front of the gathered group.

“We rehearsed this back at Pearl’s,” Albert said. “One at a time, each in order of your place on the wheel, place your hand on the appropriate mark on the door. Then take the brush, write your name, and sign within the space. Step away quickly so the next can follow. I will open the door.”

“I still think . . .” Riprap began.

“No,” Albert said. “We settled that earlier. Danger or not, this is my place. My ancestor alone did not agree to exile. Moreover, it’s about time one of my family started acting like a leader.”

Riprap shrugged, but judging from the glances he exchanged with Flying Claw, both young men were agreed that if they were attacked, their first job would be getting Albert out of the way and themselves through first.

Loyal Wind didn’t disagree with their feelings. Indeed, he might have been conspiring with them, except that three would crowd the available space.

He decided instead to keep a careful eye on Twentyseven-Ten , Shackles , and Thorn, for these three were the least reliable of their company. True, they had sworn oaths, but oaths—even those magically enforced—had been broken in the past. He noticed that Brenda Morris was also watching those three, and smiled.

She’d be a good Rat someday.

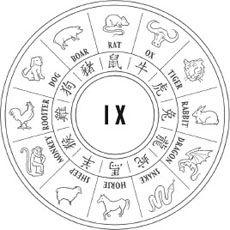

Then an odd thought hit him. The Orphans had taken their affiliations with the twelve Earthly Branches with them when they had been exiled. Two parallel series of associations had developed over time. What would happen now that the Exile was about to end? Would those separate associations continue? And who would have prior claim? Those truly of the Lands or these hybrids from elsewhere?

Unease welled within Loyal Wind, but it was too late to ask questions, even if he had wanted to do so. The Houses of Construction and Expansion had made their marks. Gentle Smoke was finishing for the House of Mystery. It was his turn, as the first member of the House of Gender. He stepped up and wrote his name, then beneath it the sign for Horse.

He handed the brush to Copper Gong, stepped back and watched her quickly write her name and sign. The brush went to Bent Bamboo, then to Des Lee, to Riprap, and finally to Deborah Van Bergenstein. The Pig finished writing her sign, handed the ink brush to Shen Kung, who methodically began to stir the bristles in a cup of water he held ready. His gaze never left Albert Yu as the Cat strode forward.

Mien lordly, head held high, Albert Yu laid his hand on the door pulls. The inked characters flared with light. Although each had been written in black ink, now they shone with the colors associated with each of the twelve branches.

Beneath Albert’s hands, the doors moved easily, so easily that Albert had to let go of one side or be inelegantly stretched between the panels. The Cat stepped gracefully to the right, and when he was wholly clear, a brilliant flash of white light lit the revealed space.

Despite its brilliance, this light did not blind, but revealed. And seeing what it revealed, Loyal Wind shouted in shock and dismay.

Nor was his voice the only one to do so.

Pearl heard

someone shout.

Perhaps Pearl herself had been the one who had spoken, but what would she have said? What could anyone have said?

The vista exposed by the opening of the Ninth Gate defied the mind’s ability to impose order.

Take the elements of a classic Chinese landscape painting: a placid lake, a rocky hillside, twisted trees, flowering shrubs, mountains in the background, a pagoda or little shrine to draw focus to the foreground.

Now render this landscape not in usual blue-blacks and greys of more or less diluted ink, but in the vivid colors of the natural world. Emphasis on vivid. These were ur-colors, primal and forceful: pinks that played cymbals, greens as salty as fresh tears, blues that smelled of wintergreen and orange blossom, purples that tickled your skin like fluff from a dandelion.

The painter of this scene must have been the bastard son or daughter or perhaps hermaphroditic hybrid of Salvador Dalí and M. C. Escher. Orientations were askew. Half the mountain range pointed quite correctly toward the heavens, but each distinct element of the other fifty percent seemed to be choosing its own orientation at whim: down, up, side to side, shifting just as you thought you had the hang of it.

The lake surface bulged out then retracted, a shimmering nacreous soap bubble that won’t quite burst. That’s probably a good thing, because there’s something in that bubble, something that seemed to be trying to get out. Light glinted from razor-edged claws.

That pagoda housed something that was eating the flowering shrub, regurgitating the petals in a confetti rainbow that scatters itself on the rocks and sticks there—but only for a moment, because the rocks they are a’rolling.

The entire scene is unfixed. It spins and twists, each moment revealing some new aspect until there is nothing left but the idea that once there was something in front of your eyes that resembled a classic Chinese ink brush painting, while what you’re looking at now resembles nothing so much as a paint box that has had water, oil, and a smattering of insects (don’t forget spiders, ants, and centipedes) spilled in it, and they’re all walking in different directions.

Some of them are walking right toward you.

“Back!” a voice yelled, and Pearl was astonished to realize that it was her own. “Get back! Something is wrong. Somehow the guardians must have oriented the Ninth Gate incorrectly. This cannot be the Lands.”

For reassurance she glanced at those from the Lands, because if they were looking at this scene as if it were old home week, then the Lands of her ancestors was a lot stranger than Pearl imagined.

But Righteous Drum, Honey Dream, and Flying Claw all looked shocked. Stunned, even—as did Twentyseven-Ten, Thorn, and Shackles.

“Keep moving away,” Pearl commanded, and felt unreasonably pleased that her voice sounded something like normal.

Everyone obeyed—although no one turned their backs on that twisting, swirling vista.

The space beneath the waters that held the Ninth Gate stretched to accommodate their retreat—a good thing, for if it had not, the next arrival would certainly not have had room to join them.

A gigantic white tiger appeared in the space between the cluster of frightened and confused humans and the open Ninth Gate. He was a very large tiger, and his presence effectively blocked the chaotic vista behind him.

Normally the arrival of a gigantic white tiger in a tightly confined space would have been a reason for panic. This time, although the sight of Pai Hu, the White Tiger of the West, filled Pearl with awe and a healthy amount of terror, what she overwhelmingly felt was a wash of relief.

“I must inform you,” Pai Hu said in a voice that held more of growl than purr in rumbling bass notes, “that neither I nor any of the other three guardians erred when setting up the Ninth Gate. As you requested, this gate opens into the Lands Born from Smoke and Sacrifice—as they have been transformed by the actions of those who now rule.”

Silence met Pai Hu’s announcement, silence broken only by the sounds of the colors blossoming and singing softly on the other side of the Ninth Gate.

Then Flying Claw said very softly, “So is our home completely gone? Are our families destroyed?”

Pai Hu twitched his ears, distracted by the strange sounds coming from the gate. “I do not know, little cousin. My realm is one of the interstitial lands—a land between and of the border, related yet distinct. I have no personal knowledge of what goes on within the Lands.”

“Ah,” Flying Claw said. His handsome face was stern and set, but Pearl saw the wet brilliance of involuntary tears in his dark eyes.

“Yet,” Pai Hu continued, “I believe—and this is belief only—that the chaos you see through this gate is not the whole of what is within. We—my fellow guardians and I—have consulted with hsien whose dwelling places are more intimately related to the Lands. They admit that their contact to the Lands is dimmed—as if a fog has arisen—but even through that fog they sense something of the Lands they knew.”

“Hsien?” Des Lee said, a note of question in his voice. “You wouldn’t be referring to an entity such as Yen-lo Wang, would you, great and honored guardian of the West?”

“I might,” said Hu Pai, “and do. As you and your associates have noted before, death connects all places.”

“But what has happened?” Honey Dream asked, her usually melodious voice tight and shrill. “Did you choose some place where this storm rages in order to draw our attention to the changes?”

“We chose the location your father requested,” Pai Hu said, the faintest note of reprimand sharpening his words. “A place where he said he had associations with a certain chiao from whom he hoped to gain knowledge.”

“Great Guardian of the West,” Righteous Drum said, “forgive my daughter her foolish words. I have spoken to that very chiao and from that alone she should have know the gate was set in the correct location. She is young and overwhelmed.”

“For good reason,” Pai Hu replied. “This is a sight to overwhelm more than youth—my fellow guardians and I are deeply concerned.”

“But you didn’t warn us,” Gaheris Morris said sharply. “Why not?”

Pai Hu turned a level amber gaze on Gaheris, and Pearl remembered that the Tiger had no reason to love the Rat. Gaheris obviously realized he’d been completely out of line.

“I’m sorry,” he said, lowering himself quickly despite his formal robes, and kowtowing to the White Tiger. “I guess Honey Dream isn’t the only one who is panicked. I thought we were nearly done. I thought this was almost over and now . . . this.”

“This,” Pai Hu repeated, and the twitch of his whiskers gave Gaheris permission to rise. “Yes. What will you do now, Orphans and allies? Do you continue on, or do we seal the Nine Gates?”

“We go on,” said Flying Claw without hesitation. Only after speaking did he look at the others. “At least I will go on—if I can figure out how one progresses through a landscape that mutates underfoot. As I see it, my responsibilities are twofold. First, I owe our allies in the Land of the Burning some idea as to whether they can expect further aggression from the Lands Born from Smoke and Sacrifice. Second, I owe those I left behind—allies and family both—what small aid I can offer.”

Righteous Drum forced out a dry laugh. “Eloquent, especially for a young Tiger. I could not have put matters more clearly myself.”