First Among Equals (4 page)

Read First Among Equals Online

Authors: Kim; Derry Hogue; Wildman

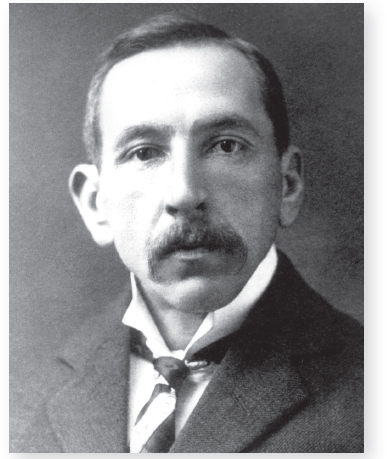

During the election campaign, however, war broke out in Europe. In one of his last acts as prime minister, Cook pledged his government's full support to the British Empire and immediately launched a recruiting campaign for the first Australian Imperial Force.

Cook remained as opposition leader until William Morris Hughes' push for conscription split the Labor Party in 1917. Hughes then formed a coalition with Cook's Liberal Party to become the Nationalist Party. Under Hughes, Cook served as navy minister from 1917 to 1920 and as treasurer from 1920 to 1921. He also joined Hughes as one of Australia's delegates at the Treaty of Versailles in 1919.

In 1921 Cook retired from politics and replaced Fisher as Australia's high commissioner in London and served as an Australian delegate to the League of Nations in the 1920s. On retirement in 1927, Cook returned to Australia where he died in Sydney some twenty years later on 30 July 1947.

WILLIAM MORRIS HUGHES

THE LITTLE DIGGER

TERM

27 October 1915-9 February 1923

T

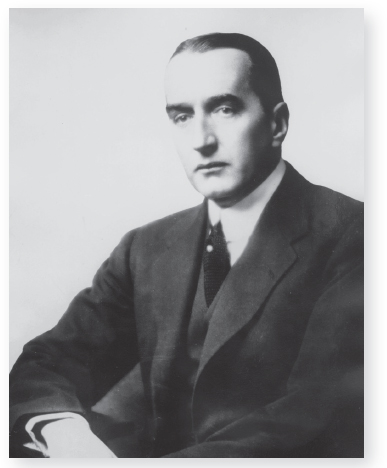

he longest-serving Australian parliamentarian, William âBilly' Morris Hughes was one of the most memorable, colourful and controversial leaders this country has seen. He was the only prime minister to have led both the Labor and conservative parties and be expelled from both.

Hughes was born in London on 25 September 1862 to Welsh parents Jane and William Hughes. After his mother's death, when he was six years old, Hughes was raised by his aunt in Llandudno, Wales, where he attended school. In 1874 he returned to London to complete his schooling at St Stephen's School, Westminster, becoming a student teacher there in 1879.

In 1884, at the age of 22, Hughes emigrated to Queensland, where he remained briefly before settling in Sydney two years later. While boarding in the suburb of Moore Park, Hughes began a de facto relationship with his landlady's daughter, Elizabeth Cutts. In 1890 the couple moved to Balmain with their two children. A year later they opened a shop from where he sold political pamphlets and did odd jobs. Hughes' shop became a centre for political debates, resulting in the formation of the Australian Socialist League in 1891.

In 1894 Hughes spent eight months in central New South Wales organising the Amalgamated Shearers' Union. That same year he then won the legislative seat

of Lang for the Labor Party, which he retained until 1901. While in parliament he became the secretary of Sydney's Wharf Labourers' Union and founded the Waterside Workers' Federation in 1899.

Following Federation, in March 1901 Hughes won the seat of West Sydney. After studying law part-time, he was admitted to the Bar in 1903. A year later he was appointed the minister for external affairs in Watson's first Labor government. In 1906, Elizabeth died of heart disease. In 1910, Hughes met Mary Campbell, a daughter of a New South Wales grazier, and married her a year later.

Hughes went on to serve as attorney-general in Fisher's three Labor governments. However, an ambitious Hughes wanted the Labor leadership for himself. Hoping to defuse the situation, Fisher offered Hughes the office of high commissioner in London. Hughes refused and Fisher resigned and took the post himself in 1915, leaving the primeministership to Hughes.

Dubbed âthe Little Digger' for his staunch stance on compulsory military service, Hughes immediately began campaigning to expand Australia's war effort. After travelling to Britain and then visiting Australian troops on the front line in France, Hughes returned to Australia in 1916 and immediately launched a âyes' campaign to introduce conscription through a referendum. The

question of compulsory military service, however, not only divided the country, but ultimately his party. Following the referendum's defeat on 28 October 1916, Hughes was expelled from the New South Wales Labor executive and the Wharf Labourers' Union.

At a bitter caucus meeting on 14 November, Hughes and his followers walked out. They then formed the National Labor Party and, after negotiations with Liberal leader Joseph Cook, created the National Party, which, with Hughes at the helm, easily won the May 1917 election.

Faced with the heavy loss of Australian lives in the war and a sustained drop in recruitment, Hughes called another referendum. Held in December 1917, the referendum was again defeated, this time by a wider margin, and Hughes resigned. However, as no other party had the numbers to take power, governorgeneral Munro-Ferguson asked Hughes to form an administration.

In 1919 Hughes and Cook travelled to Europe to attend the Versailles peace conference where he lobbied for Australia to become a full member of the League of Nations and secured Australian control over New Guinea. Back home he easily won the December 1919 election, though was only able to hold on to the prime-ministership for another two years. Following the federal election at the end of 1922, the new Country

Party headed by Earle Page refused to serve under Hughes, forcing him to resign on 2 February 1923. Stanley Melbourne Bruce was his successor.

After being forced out of the National Party, Hughes then went on to serve under the United Australia Party (UAP) governments of Joseph Lyons, Robert Menzies and Arthur Fadden. Always controversial, Hughes was forced to resign from the party in 1935 after publishing a book,

Australia and War Today,

which openly criticised the Lyons' government use of economic sanctions to combat German rearmament.

However, in 1936, Hughes returned to cabinet as minister for health and repatriation and was then reappointed as the minister for external affairs in 1937. In 1939 Hughes made another bid for the leadership but was narrowly defeated by Menzies, once again becoming deputy leader. Following the outbreak of World War II, Hughes was appointed to the Advisory War Council.

In 1944 Hughes joined Menzies' newly formed Liberal Party and became the member for Bradford. He remained in parliament until his death in October 1952. His state funeral in Sydney was one of the largest in Australian history, attracting more than 100,000 people. His 51-year, seven-month record stint as a serving member of parliament has not been broken to date.

STANLEY MELBOURNE BRUCE

THE QUINTESSENTIAL ENGLISHMAN

TERM

9 February 1923-22 October 1929

T

he ascension of Stanley Melbourne Bruce, a decorated war hero, to the prime-ministership in 1923 marked a distinct turning point in Australia's political history. An Australian by birth, he was the quintessential Englishman, complete with spats and Rolls Royce. Moreover, he was the first prime minister not to have sat in a colonial parliament, nor to have been involved in the movement for Federation.

Bruce was born on 15 April 1883 in Toorak, Melbourne. The youngest of five children of John Munro Bruce and Mary Henderson, Bruce was educated at Melbourne Grammar School. In 1902, a year after his father's death, he moved to England to study Law at Cambridge University. After graduating Bruce settled in London where he practised as a barrister and was chairman of the London board of his family's thriving Melbourne-based importing business.

In 1913 Bruce married fellow Melburnian Ethel Dunlop Anderson. A year later when World War I broke out, he was commissioned as an officer in the British Army and fought at Gallipoli and on the Western Front, winning both the Military Cross and the

Croix de Guerre avec Palme.

Wounded in action, he was invalided to London. Returning to Melbourne in 1917 to run the family business, Bruce soon became involved in Australia's war-recruitment campaign. Attracting the attention of the National Party, he was

persuaded to run for the federal seat of Flinders in May 1918. Bruce won the seat comfortably and retained it for the next four elections.

In 1921 while Bruce was in Europe on business, the incumbent prime minister, William Morris Hughes, pressed him to represent Australia at the League of Nations. Upon returning home Hughes rewarded Bruce with the treasury portfolio. After Hughes was forced to resign in 1923, Bruce became Australia's eighth prime minister after only five years in politics.

Bruce quickly adopted a âmen, money and markets' policy for economic development within an Imperial framework. He argued that if Australia was to continue to take in British immigrants, then the British Empire was obligated to protect Australia's growing industry through preferential tariffs, a point he made clear at the 1923 Imperial Conference held in Britain.

During his tenure as prime minister, Bruce hastened the development of Canberra as the national capital, which had been suspended while Australia was at war. The first meeting of federal parliament in Canberra took place on 9 May 1927 after an opening ceremony attended by the Duke of York (later King George VI).

With the 1917 Russian Revolution still recent history, Bruce exploited the fear of Communism, introducing anti-union legislation and proposals such as abandonment of the arbitration system. Between

1927 and 1929 mounting industrial tensions led to violent strikes in all major industries including timber and mining. Despite the ongoing conflict and the Labor Party's efforts to censure the government, Bruce won another term in the 1928 election.

Frustrated by the ongoing disputes, in 1929 Bruce tabled the

Maritime Industries Bill

abolishing the federal arbitration system and transferring powers to the states. However, the bill was defeated, ultimately bringing down the government. At the subsequent election on 10 October 1929, Labor won in a landslide victory. More surprisingly, Bruce lost his own seat, becoming the only sitting prime minister until John Howard, 79 years later, to suffer such a fate.

While Bruce eventually won back the seat in 1931, he resigned two years later to become high commissioner in London. Serving in the post for twelve years, Bruce was well respected by the British âestablishment' and in 1947 was raised to peerage as the Viscount Bruce of Melbourne, the only Australian ever to receive this honour. He later represented Australia on various boards of the United Nations and was appointed the chancellor of the Australian National University. Bruce died in London on 25 August 1967 at the age of 84.

JAMES HENRY SCULLIN

THE ILL-FATED PRIME MINISTER

TERM

22 October 1929-6 January 1932

W

hen Australia's ninth prime minister, James âJim' Henry Scullin, assumed office in October 1929 it was a major victory for the Labor Party which had spent thirteen years in opposition. Yet Scullin's triumph was short-lived as events such as the Wall Street Crash and the Great Depression conspired against him and ultimately brought down his government two years later.

Scullin was born in Trawalla, Victoria, on 18 September 1876. He was the fifth of nine children to parents John and Ann, who had emigrated from Derry in Ireland. Scullin was educated at local state schools, before leaving at the age of fourteen to work as a grocer in Ballarat. He continued his education through night school and honed his public-speaking skills as a member of the Catholic Young Men's Society.

In 1903, Scullin joined the Political Labor Council, a forerunner of the Australian Labor Party, and later became an organiser for the Australian Workers' Union. At the December 1906 federal election he stood as a Labor candidate for the seat of Ballarat, though was beaten by incumbent prime minister, Alfred Deakin.