First Among Equals (10 page)

Read First Among Equals Online

Authors: Kim; Derry Hogue; Wildman

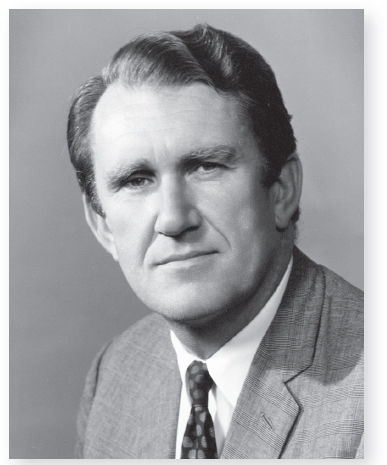

Following the 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor, Whitlam enlisted in the Royal Australian Air Force. In April 1942 he married Margaret Dovey, the daughter of a prominent judge. Six weeks later Whitlam was stationed to Gove in the Northern Territory, where he served as a navigator for much of the war. While in service he campaigned for Labor in the 1944 referendum to give the Commonwealth wider post-war reconstruction powers.

Discharged in 1945, Whitlam returned to Sydney where he joined the Darlinghurst branch of the Labor Party. He then completed a law degree, and was admitted to the Bar in 1947. In 1950, he unsuccessfully contested the seat of Sutherland in the state elections,

though in 1952, he won the federal seat of Werriwa in a by-election.

In 1959 Whitlam was elected to the caucus executive and the following year became the Labor Party deputy under Arthur Calwell. Whitlam's relationship with Calwell was uneasy and the two men clashed on state aid and the war in Vietnam. However, after Calwell lost to Harold Holt in the November 1966 elections, Whitlam succeeded him as the opposition leader in February 1967.

A formidable campaigner, Whitlam came close to victory against John Gorton in the 1969 elections, falling only four seats short of a majority. With the Coalition buckling after a marathon 23 years in power, in December 1972 Whitlam, who had campaigned on the slogan âIt's Time', won the election and the primeministership.

Once in office Whitlam embarked on a sweeping program of social reforms, introducing free tertiary education, universal health care, equal pay for women, assistance for Aboriginal communities and increased funding for the arts. He also ended conscription, abolished the death penalty, and eradicated the last traces of the White Australia policy. In addition, Whitlam resumed diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China after 24 years, becoming in 1973 the first prime minister to visit the country.

While Whitlam's Labor government was making steady progress, its legislative program met constant resistance in the Senate. In April 1974 a double dissolution was triggered after the Senate's repeated rejection of bills to set up Medibank. Labor was returned to power, but with a reduced majority.

Whitlam continued his program of reform but was soon entangled in a number of controversies. The âLoans Affair' in which several of Whitlam's ministers, including Rex Connor and Dr Jim Cairns, secretly attempted to raise US$4 billion in foreign loans and then misled parliament about their activities was particularly damaging. While both ministers were subsequently sacked, opposition leader Malcolm Fraser used the situation to his advantage to force an early election, but to no avail.

In October 1975 Fraser took the divisive step of blocking the passage of the government's budget bills, exploiting a narrow majority in the parliamentary Upper House. Whitlam, however, refused to call a general election. For almost a month, parliament was deadlocked. Finally, on 11 November the governorgeneral, Sir John Kerr, stepped in and dismissed the Whitlam government.

Whitlam's âdismissal' provoked public outrage and was immortalised by Whitlam's response to an assembled crowd on the steps of Parliament House:

âLadies and gentlemen, well may we say God Save the Queen, because nothing will save the governor-general.' Fraser was appointed as caretaker prime minister and won the subsequent election by a landslide.

Whitlam stayed on as opposition leader for two years and then retired to the backbench until 1978 when he resigned from parliament. Despite the controversy, Whitlam remained a leading figure in the Labor Party. In 1999 he campaigned together with his old enemy Fraser on the referendum regarding Australia becoming a republic. Since 2000 Whitlam helped develop the Whitlam Institute at the University of Western Sydney and in November 2005 donated his letter of dismissal and his âIt's Time' campaign speech to its archives. Margaret, his wife of nearly 70 years died on 16 March 2012 at the age of 92. Whitlam's own health had deteriorated and he died in a nursing home at Elizabeth Bay in Sydney on 14 December 2014, aged 98. A state funeral at Sydney Town Hall was televised nationally.

JOHN MALCOLM FRASER

THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD

TERM

11 November 1975-11 March 1983

A

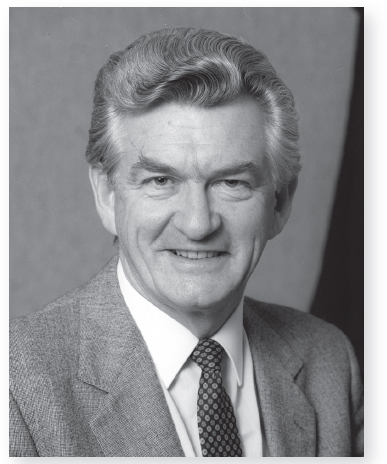

ustralia's twenty-second prime minister, John Malcolm Fraser will long be remembered for the extraordinary manner in which he came to power following the dismissal of the Whitlam government. Despite his progressive policies, Fraser â who earned the nickname âChairman Mal' for his brusque style of leadershipâwas never able to escape the dark shadow the controversy cast over his prime-ministership.

The second child of John Neville and Una Fraser, he was born on 21 May 1930 in Toorak, Victoria. Fraser's family also had a hand in Australia's early political history with his grandfather, Simon Fraser, serving in the Victorian parliament and participating in the Federal Conventions of 1897-98 before becoming a senator at Federation.

Fraser was educated at Tudor House in Moss Vale, New South Wales, and then Melbourne Grammar School. While only an average student, he worked diligently, and consequently, in 1949, gained a place at Magdalen College at Oxford University, where he studied philosophy, politics and economics. After graduating in 1952, he returned to Australia to manage one of his father's properties.

In 1954 Fraser unsuccessfully contested the federal seat of Wannon as the Liberal candidate at the general election. The next year, however, he won the seat, becoming, at the age of 25, the federal parliament's

youngest member. In December 1956 he then married Tamara âTamie' Beggs, the daughter of a Victoria property owner.

Fraser spent his first eleven years in parliament languishing on the backbench, until Menzies retired in 1966 and the new prime minister, Harold Holt, appointed him minister for the army. Following Holt's disappearance and John Gorton's rise to power, Fraser was offered several more ministerial portfolios including education, science and defence. However, disenchanted with Gorton's autonomous style of governing, Fraser resigned on 10 March 1971, setting in motion a chain of events that led to Gorton's demise.

When William McMahon then became prime minister, Fraser again became the minister for education and science. After Whitlam swept the Liberal Party from office in 1972, Fraser waited two years before he challenged Billy Snedden for the Liberal leadership and lost. In March 1975 Fraser finally won the leadership and immediately began using the conservative's control of the Senate to block the money supply to the Whitlam government. The deadlock lasted for weeks and climaxed when the governor-general, Sir John Kerr, dismissed the Whitlam government and appointed Fraser as a caretaker prime minister. In the ensuing election, the Liberal Party won by an overwhelming majority and Fraser became prime minister.

Once in power, Fraser worked to reduce government expenditure, slashing public-service salary spending and the budgets for the environment, arts and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. When criticised for not making more sweeping cuts and for providing tax breaks for industry while imposing austerity on working-class Australians, Fraser famously quipped: âLife wasn't meant to be easy'.

Like Whitlam, Fraser was a strong supporter of multiculturalism and continued implementing some of his predecessor's policies, including expanding immigration from Asian countries and passing legislation to give Aboriginal people control of traditional lands in the Northern Territory. Fraser was also a staunch opponent of apartheid and played a key role in securing the independence of Zimbabwe in 1980.

In early 1983, with Fraser's government reeling from a scandal over tax-avoidance schemes run by prominent Liberal Party members, Andrew Peacock unsuccessfully challenged Fraser's leadership. Despite a back injury that saw Fraser hospitalised, he called a snap election hoping to catch out the Labor Party which was besieged by a leadership crisis. However, on the day the election was called, Robert Hawke replaced Bill Hayden as opposition leader and Fraser ultimately lost the 5 March election in a crushing Labor Party

victory. In conceding defeat, a visibly shaken Fraser immediately announced his resignation from the Liberal Party leadership.

After standing down as leader and retiring from parliament, Malcolm Fraser became an active humanitarian. In 1991 he became president of Care International; in 1997 he led a Commonwealth election observer mission to Pakistan; and, in 1999, he helped secure the release of two Australian aid workers who were gaoled in Kosovo. He was awarded Australia's Human Rights Medal in November 2000. Fraser also distanced himself from his former party, openly criticising their policies regarding refugees, terrorism and the loss of civil liberties, in 2006. He and Gough Whitlam not only reconciled their past bitter political struggle, but became friends, united on a range of social issues at odds with the party Fraser had once led. Soon after Tony Abbott won the Liberal leadership in 2009, Fraser resigned from the party, saying it was âno longer a liberal party but a conservative party'. He said

he

had not changed but the party had changed, and in his last years even gave his support to a Greens Party candidate.

Malcolm Fraser died after a short illness on 20 March 2015, survived by his wife Tamie and their four children. He was given a state funeral at The Scots' Church in Melbourne on 27 March 2015.

ROBERT JAMES LEE HAWKE

CONSENSUS MAN

TERM

11 March 1983-20 December 1991

A

ustralia's longest-serving Labor prime minister, Robert James Lee Hawke, was the antithesis of his conservative predecessor. A former trade union leader, Hawke was a charismatic, gregarious, approachable leader who preferred to be known as âBob'. Coming to power during the prosperous early 1980s, he enjoyed wide popularity which saw him win four consecutive federal elections.

The younger of the two sons of Clem and Ellie Hawke, he was born in Bordertown, South Australia, on 9 December 1929. After Hawke's older brother Neil died of meningitis, the family moved to Perth, Western Australia, in 1939. An excellent student, Hawke attended Perth Modern School, before enrolling at the University of Western Australia. In 1953 Hawke won a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford University, graduating with a Bachelor of Letters in 1955. During his time at Oxford, Hawke gained notoriety by setting the

Guinness

world record for drinking two-and-a-half pints of beer in twelve seconds.

In 1956 he returned to Australia to take up a research scholarship at the Australian National University in Canberra. That same year he married Hazel Masterson, whom he had met eight years earlier. In 1958 Hawke accepted a position with the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) and the couple moved to Melbourne. He then stood unsuccessfully for the federal seat of Corio in 1963; however, he was elected president of the ACTU in 1969.

Having joined the Labor Party in 1947 at the age of seventeen, Hawke went on to serve as its president from 1973 to 1978. He was a key figure in Whitlam's 1972 âIt's Time' campaign, and following Whitlam's dismissal in 1975, it was ironically Hawke who called for calm. In 1979 after suffering a physical collapse, Hawke finally recognised he had a drinking problem and set about conquering his addiction.

In 1980 Hawke moved into federal politics, winning the seat of Wills, and was immediately elevated to the opposition front bench. With then opposition leader Bill Hayden unable to defeat Malcolm Fraser, in July 1982 Hawke made his first unsuccessful challenge for the ALP leadership. With the Labor Party leadership under question, Fraser decided to seize the opportunity and called an early election. However, the Labor Party had anticipated this move and on the same day announced that they had replaced Hayden with Hawke. As a result, after only one month as party leader, Hawke became Australia's twenty-third prime minister.

Having learnt from the Whitlam debacle, Hawke moved quickly to fulfill his campaign promises. He held the successful National Economic Summit in Canberra, blocked construction of a hydro-electric scheme on the Franklin River in Tasmania, privatised

state sector industries, restructured the tariff systems and social welfare and, with Paul Keating as his treasurer, reduced personal income tax and implemented the historic Prices and Income Accord agreement with the unions.