Firebirds Soaring (5 page)

Authors: Sharyn November

“They can’t

all

live in that shack,” Jason said.

all

live in that shack,” Jason said.

“They can and do,” said Three Aces.

“Shin Bone!” the people called from the porch. “You’ve come home at last! We’re all so glad to see you!”

“I’m not him,” Jason said, shrinking against Chicago Danny. “I’m not even the right color.”

“They see what they hope to see. Now run along and make them happy,” said the angel. So Jason was swept into the middle of Shin Bone’s family, and they made a big fuss over him. They fed him corn pone and fatback and many other things he’d never heard of but that tasted good. Best of all were the long, lazy evenings when everyone crowded together to tell stories. And nobody was left out, not even the great grandma, who never left her bed and who you had to shout at because she was deaf.

One night, very late, Jason sat on the porch with Beauty. Stars filled the gap between the mountains on either side. Mockingbirds sang as they did on warm nights, for it was summer here and had been for years. Jason heard, far off, coming through the mountains, the long, low whistle of a train.

He stood up as it chuffed to a halt, gave Beauty a last friendly pat, and climbed into the boxcar.

“Welcome back,” said Chicago Danny from the shadows.

“We were counting on you,” said Three Aces. The train went off through the mountains, away from the dog, the farmhouse, and Shin Bone’s family sleeping inside.

“Counting on me for what?” asked Jason.

“To put things right. You see, most people travel only one way. They go into the past until they find the best time of their lives and there they stay. But not Shin Bone and not you. You’re just naturally restless. You’re happiest

on

the train, looking for what’s around the next bend.”

on

the train, looking for what’s around the next bend.”

“What if I hadn’t got restless?” Jason said.

“The train would never have returned.”

Again they crisscrossed America, finding stops they hadn’t seen before and revisiting some of the others. Clothing fashions changed; cars got longer, sprouted tail fins, and shrank again; the blue light of television flicked on behind window shades. And one night they pulled up in front of the library. The windows were dark, and frost covered the grass. Shin Bone stood under his favorite tree, waiting.

“What’ve you been doing since we left? ” asked Jason, glad to see the old hobo look so healthy and happy.

“Haunting the library,” admitted Shin Bone. “That’s what happens to people who lose their ticket. They become ghosts. I amused myself by hiding in the stacks and flushing toilets. Mike drove himself crazy trying to catch me, but he never did. He’s in a nice rest home now, I hear.”

“I guess this is yours,” Jason said regretfully, holding out the ticket.

“What are you going to do now?”

“Oh . . . I don’t know.” Jason looked at the dark city all around, at the ice coating the dark street. He had no idea how long he’d been gone or what would happen when he returned to the group home.

“Why don’t you come with me?” suggested Shin Bone.

“I don’t have a ticket.”

The old man grinned. “I’ve been riding boxcars for fifty years and never once—not once!—did I have a ticket. Stick with me, kid, and we’ll go places.”

They both climbed onto the train. “You made it!” hollered Chicago Danny, slapping Shin Bone on the back.

“Welcome home,” cried Three Aces. “Just look at that view!”

The train picked up speed, and the countryside rolled by like life itself, field after valley after mountain range, with here and there the lights of a small farm. The air rushed past, scented with pine needles and sage.

“It never disappoints,” said Shin Bone as the whistle sang its way through the sleeping towns and cities of America.

NANCY FARMER

grew up in a hotel on the Mexican border. As an adult, she joined the Peace Corps and went to India to teach chemistry and run a chicken farm. Among other things, she has lived in a commune of hippies in Berkeley, worked on an oceanographic vessel, and run a chemistry lab in Mozambique. She has published six novels, four picture books, and six short stories. Her books have won three Newbery Honors, the National Book Award, the Commonwealth Club of California Book Silver Medal for Juvenile Literature, and the Michael L. Printz Honor Award. Her Web site is

www.nancyfarmerbooks.com

.

grew up in a hotel on the Mexican border. As an adult, she joined the Peace Corps and went to India to teach chemistry and run a chicken farm. Among other things, she has lived in a commune of hippies in Berkeley, worked on an oceanographic vessel, and run a chemistry lab in Mozambique. She has published six novels, four picture books, and six short stories. Her books have won three Newbery Honors, the National Book Award, the Commonwealth Club of California Book Silver Medal for Juvenile Literature, and the Michael L. Printz Honor Award. Her Web site is

www.nancyfarmerbooks.com

.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

“A Ticket to Ride” was inspired by an elderly homeless man who camps outside our local library. He is clean and well spoken, doesn’t take drugs or drink alcohol. Most of the time he lies in wait for library patrons because he loves talking and can do it for hours. But there is nothing wrong with his sanity. “Shin Bone” (not his real name) is simply one of those people who can’t live too close to others. He has to be outdoors and he needs total freedom. He would have been perfectly happy living in the Stone Age, and I find him thoroughly admirable.

Christopher Barzak

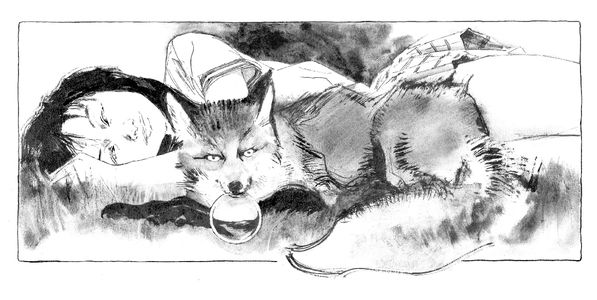

A THOUSAND TAILS

W

hen I was five years old, my mother gave me a silver ball and said, “Midori chan, my little

kitsune

, don’t let Father know about this. He’d take it from you to sell it, but it’s yours, my little fox girl. It’s yours, and now you can learn how to take care of yourself.”

hen I was five years old, my mother gave me a silver ball and said, “Midori chan, my little

kitsune

, don’t let Father know about this. He’d take it from you to sell it, but it’s yours, my little fox girl. It’s yours, and now you can learn how to take care of yourself.”

“You mean I can learn how to take care of the ball,” I said. Even then I was not polite as I was supposed to be. I was a girl who corrected her mother.

“No, no,” said my mother. “So you can learn how to take care of yourself. That’s what I said, didn’t I? ” She swatted a fly buzzing near her nose and it fell to the floor, stunned by the impact, next to her bare foot. The next moment she crushed it beneath her heel and continued. “A fox always takes care of itself by taking care of its silver ball. Don’t you remember the stories I’ve told you? Well, I’ll tell them again, my little one. So listen and you’ll know what I mean.”

My mother had always called me her fox girl, had always told me she’d found me wandering in the woods and brought me home with her. Father would laugh and say, “Your mother is always bringing home lost creatures. Soon we’ll be keeping a zoo!” He’d stroked the back of my head like I sometimes saw him pet our cats: one long stroke and a quick pat to send me off again.

As a child I was often confused by the things my mother said and did, but it didn’t bother me. It felt natural that life was mysterious and that my mother hid her meaning behind a veil of stories, as if her words were water through which truth shimmered and splintered like the beams of the rising sun. She taught me that some matters have no clear way to explain their meaning to others.

Children at school often remarked on her. How strange your mother is, they told me. And how alike the two of us were. “Why does your mother speak to herself? Why does she sometimes laugh at nothing? Is she crazy?” a small group once asked me at recess, forming a circle around me. “Why do you sit in class and stare out the window while we’re playing

karuta

or Fruit Basket? Why don’t you talk to us, Midori? What’s the matter? Don’t you like people?”

karuta

or Fruit Basket? Why don’t you talk to us, Midori? What’s the matter? Don’t you like people?”

To tell the truth, they were correct. I was a strange child, and they sensed it. It was because, even then, people seemed so odd to me in their single-minded concerns and simple pleasures. I did not know at the time why, at the age of five—at an age before the world had had time to inflict many wounds on me—I felt this way. Somehow, though, I felt somewhere a world existed that was my true home, not the rice fields or the gray mountainsides in the distance, not the rivers and the fishermen standing along their banks, not the dusty fields where other children played games during afternoon recess, not the farm on which I was being raised, not the little town of Ami. And it was not that I felt I belonged in a radiant, carnivalesque city like Tokyo either. It was that I somehow knew I simply did not belong with people.

I knew all that at the age of five. But it was at nine years old that I discovered my true being in this world.

In fourth grade we read a book called

Gongitsune

. This is an honorable way of spelling and saying the name of the fox, the

kitsune

. Many of the new

kanji

we were learning that month were in this tale, and beside each new character the publisher had printed small

hiragana

, the simpler alphabet, to guide us to the right sound and meaning. I didn’t need

hiragana

as much as the others, though.

Kanji

was easy for me. When

sensei

introduced new characters, it seemed I could look at them and, almost by magic, they would reveal their meanings to me, yet one more reason for my classmates to be suspicious. So when

sensei

gave us this story, I read for pleasure, I read without having to study our new words.

Gongitsune

. This is an honorable way of spelling and saying the name of the fox, the

kitsune

. Many of the new

kanji

we were learning that month were in this tale, and beside each new character the publisher had printed small

hiragana

, the simpler alphabet, to guide us to the right sound and meaning. I didn’t need

hiragana

as much as the others, though.

Kanji

was easy for me. When

sensei

introduced new characters, it seemed I could look at them and, almost by magic, they would reveal their meanings to me, yet one more reason for my classmates to be suspicious. So when

sensei

gave us this story, I read for pleasure, I read without having to study our new words.

Gongitsune

is about a little motherless fox named Gon, who finds a small village while he is out looking for food and begins to steal from the villagers. One day Gon steals an eel from a man named Hyoju. The eel was supposed to be for Hyoju’s sick old mother. And because Gon stole the mother’s meal, the old woman dies. When Gon discovers the consequence of his actions, he tries to repent by secretly giving things he steals from other villagers to Hyoju. But the villagers see that Hyoju has their things and they beat him up, thinking he’s the thief. From then on, Gon only brings Hyoju mushrooms and nuts from the forest. Hyoju is grateful, but doesn’t know who brings him the gifts, or why. Then one day he sees a fox in the woods and, remembering the fox that stole the eel for his dying mother, he shoots, and Gon dies. It’s only afterward, when the gifts of mushrooms and nuts stop showing up on his doorstep, that he realizes it was Gon who had been bringing them all along.

is about a little motherless fox named Gon, who finds a small village while he is out looking for food and begins to steal from the villagers. One day Gon steals an eel from a man named Hyoju. The eel was supposed to be for Hyoju’s sick old mother. And because Gon stole the mother’s meal, the old woman dies. When Gon discovers the consequence of his actions, he tries to repent by secretly giving things he steals from other villagers to Hyoju. But the villagers see that Hyoju has their things and they beat him up, thinking he’s the thief. From then on, Gon only brings Hyoju mushrooms and nuts from the forest. Hyoju is grateful, but doesn’t know who brings him the gifts, or why. Then one day he sees a fox in the woods and, remembering the fox that stole the eel for his dying mother, he shoots, and Gon dies. It’s only afterward, when the gifts of mushrooms and nuts stop showing up on his doorstep, that he realizes it was Gon who had been bringing them all along.

“And what is the moral of this story?” our

sensei

asked after we finished our reading.

sensei

asked after we finished our reading.

We waited with our eyes open, our mouths sealed tight. We knew that she would deliver the answer the very next moment, that our input was not important.

“The moral is that there is an order to the world, that everything is as it is for a reason. Gon’s mother dies, Hyoju’s mother dies, Gon is shot while he tries to make amends for his mistakes, and Hyoju feels guilty after realizing he’s killed the creature that’s been helping him. But nothing can be done about this. Everyone must accept their own fate.”

We stayed silent. A few children nodded. But I didn’t like what the

sensei

said. I didn’t think the story was about accepting fate. I thought it was about how stupid Hyoju was for not trying to find out who was leaving mushrooms and nuts. Gon wasn’t that clever really. Hyoju, if he wanted to know, could have discovered Gon at any time. Instead he chose the human way. He chose the path humans almost always choose. The path of ignorance.

sensei

said. I didn’t think the story was about accepting fate. I thought it was about how stupid Hyoju was for not trying to find out who was leaving mushrooms and nuts. Gon wasn’t that clever really. Hyoju, if he wanted to know, could have discovered Gon at any time. Instead he chose the human way. He chose the path humans almost always choose. The path of ignorance.

Poor Gon

, I thought as I sat at my desk.

Poor little fox.

I stroked the picture of him struck down by stupid Hyoju’s bullet, his fur glowing white as moonlight.

, I thought as I sat at my desk.

Poor little fox.

I stroked the picture of him struck down by stupid Hyoju’s bullet, his fur glowing white as moonlight.

And there, in that moment, I realized it was Gon’s tribe that I belonged to, not the human family. I was a

kitsune

, I realized. I was a fox.

kitsune

, I realized. I was a fox.

Every

kitsune

has a silver ball that contains part of its essence. Why hadn’t I understood this when my mother gave it to me years before? I’d thought she was just telling me another of her stories, the kind she was always telling me, the kind that I hadn’t really, until that day, believed. The silver ball holds a piece of the

kitsune

’s spirit so that when it changes shape it’s never entirely separated from its original form. It made sense now. It all washed over my mind like a clear spring rain, and I stood and walked to the back of the room to gather my things.

Sensei

turned around when she heard me shuffling the backpack onto my shoulders and cried out, “Midori chan, what are you doing?”

kitsune

has a silver ball that contains part of its essence. Why hadn’t I understood this when my mother gave it to me years before? I’d thought she was just telling me another of her stories, the kind she was always telling me, the kind that I hadn’t really, until that day, believed. The silver ball holds a piece of the

kitsune

’s spirit so that when it changes shape it’s never entirely separated from its original form. It made sense now. It all washed over my mind like a clear spring rain, and I stood and walked to the back of the room to gather my things.

Sensei

turned around when she heard me shuffling the backpack onto my shoulders and cried out, “Midori chan, what are you doing?”

“Going home,” I said. I slid the door of the classroom open and walked down the hallway.

Sensei

rushed and caught me by my shoulder as I was walking out the front entrance, but I shrugged her hand off and stared up at her, making the most defiant face I could summon, and said, “Never touch me in such a way again.”

Sensei

rushed and caught me by my shoulder as I was walking out the front entrance, but I shrugged her hand off and stared up at her, making the most defiant face I could summon, and said, “Never touch me in such a way again.”

She slowly took her hand off my shoulder. Her face dropped, all the muscles relaxing, and in this way she revealed the fear I’d instilled in her. When you are a

kitsune

, you can use your powers to persuade and affect human emotions. It’s a simple trick really, especially because most humans have little control over their own emotions anyway. So even so soon after realizing what I was, I knew how to use one of the powers that is a right of all

kitsune

.

kitsune

, you can use your powers to persuade and affect human emotions. It’s a simple trick really, especially because most humans have little control over their own emotions anyway. So even so soon after realizing what I was, I knew how to use one of the powers that is a right of all

kitsune

.

At home I put my school things away and pulled my futon from the closet, unfolded it, and sat down, folding my legs under me. I took the silver ball from a box of toys and rolled it around in the palms of my hands, pressing it against my cheek occasionally. It was as warm as my own flesh, and when I held it to my ear I heard a pulse and a thump, a heart beating over and over.

Other books

A Soul To Steal (The Sanheim Chronicles, Book One) by Rob Blackwell

Laura Lippman by Tess Monaghan 04 - In Big Trouble (v5)

A Deafening Silence In Heaven by Thomas E. Sniegoski

Silver Storm: Timewalker Chronicles, Book 2 by Callahan, Michele

Seduced At Sunset by Julianne MacLean

Firelight at Mustang Ridge by Jesse Hayworth

Trusting Viktor (A Cleo Cooper Mystery) by Mims, Lee

White Jade (The PROJECT) by Lukeman, Alex

A Chosen Few by Mark Kurlansky