Firebirds Soaring (10 page)

Authors: Sharyn November

Grandmother set down her ladle, and then walked over to the railing of the junk. She motioned Yumin to join her. “Daughter’s-son, come over here.”

When Yumin reached her side, the old woman pointed over the side of the boat, down into the dark waters.

“What?” Yumin said, and leaned over the side. There, deep beneath the cold waves, he saw the glittering lights of the Sunken City.

“Remember this,” Grandmother said. “There

is

a Land in the Sea. And as we have seen, it is ruled by a mighty dragon. Things in stories can also be real. But what you will find, out there among the stars . . .”

is

a Land in the Sea. And as we have seen, it is ruled by a mighty dragon. Things in stories can also be real. But what you will find, out there among the stars . . .”

The old woman paused, a proud smile on her face as she looked up at the night sky. She reached out and took her grandson’s hand. Yumin felt safe with her calloused fingers wrapped around his.

“The things you will find, Daughter’s-son, we don’t yet know about, even in our wildest stories.”

They stood, the old woman and the young man, looking up at the heavens, as the blue-green star that was Earth rose slowly in the east.

CHRIS ROBERSON

’s novels include

Here, There & Everywhere

,

The Voyage of Night Shining White

,

Paragaea: A Planetary Romance

,

X-Men: The Return, Set the Seas on Fire

,

The Dragon’s Nine Sons, End of the Century

,

Iron Jaw and Hummingbird

, and

Three Unbroken

. His short stories have appeared in a wide variety of magazines and anthologies. Along with his business partner and spouse, Allison Baker, he is the publisher of MonkeyBrain Books, an independent publishing house specializing in genre fiction and nonfiction genre studies, and he is the editor of the anthology

Adventure Vol. 1

. He has been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award three times—once each for writing, publishing, and editing—and a finalist twice for the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer, and twice for the Sidewise Award for Best Alternate History Short Form (winning in 2004 with his story “O One”). Chris and Allison live in Austin, Texas, with their daughter, Georgia. Visit him online at

www.chrisroberson.net

.

’s novels include

Here, There & Everywhere

,

The Voyage of Night Shining White

,

Paragaea: A Planetary Romance

,

X-Men: The Return, Set the Seas on Fire

,

The Dragon’s Nine Sons, End of the Century

,

Iron Jaw and Hummingbird

, and

Three Unbroken

. His short stories have appeared in a wide variety of magazines and anthologies. Along with his business partner and spouse, Allison Baker, he is the publisher of MonkeyBrain Books, an independent publishing house specializing in genre fiction and nonfiction genre studies, and he is the editor of the anthology

Adventure Vol. 1

. He has been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award three times—once each for writing, publishing, and editing—and a finalist twice for the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer, and twice for the Sidewise Award for Best Alternate History Short Form (winning in 2004 with his story “O One”). Chris and Allison live in Austin, Texas, with their daughter, Georgia. Visit him online at

www.chrisroberson.net

.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I accidentally created a world, several years ago, and have been writing about it ever since. I’d been trying without much success to launch a career as a writer, but despite having written six or seven novels and dozens of short stories, I’d sold exactly none of them. I finally gave up doing it the “right way,” started a webzine with a few other writers, and posted my stories online for free, thinking to build an audience and a career that way, instead. Which, of course, didn’t work either, but it at least got me the attention of an editor, Lou Anders, who asked me to submit a story to an anthology he was putting together. On a plane flight home, I cooked up an alternate history story that took place in a world dominated by Imperial China, a world I eventually decided to call the “Celestial Empire.” I knew only as much about Chinese emperors as I’d seen in Bernardo Bertolucci’s

The Last Emperor

, so the Celestial Empire and its history in that first story were little more than set decoration, but the story worked well enough for the editor to buy it, for a few reviewers to comment on it favorably, and for it to be nominated for a couple of awards, winning one of them. Having written that first story, I didn’t really expect to revisit the Celestial Empire again, and went to work on other things. Then Lou asked me for another story set in the Celestial Empire, and Sharyn November at Viking asked for a novel set in the same world, and George Mann at Solaris asked for a whole

series

set in it. Needless to say, I had a

lot

of research to do, and I gradually fleshed out about twelve centuries’ worth of history, from the fifteenth century in China to the far future on a terraformed Mars. Without meaning to do so, I’d created a world.

The Last Emperor

, so the Celestial Empire and its history in that first story were little more than set decoration, but the story worked well enough for the editor to buy it, for a few reviewers to comment on it favorably, and for it to be nominated for a couple of awards, winning one of them. Having written that first story, I didn’t really expect to revisit the Celestial Empire again, and went to work on other things. Then Lou asked me for another story set in the Celestial Empire, and Sharyn November at Viking asked for a novel set in the same world, and George Mann at Solaris asked for a whole

series

set in it. Needless to say, I had a

lot

of research to do, and I gradually fleshed out about twelve centuries’ worth of history, from the fifteenth century in China to the far future on a terraformed Mars. Without meaning to do so, I’d created a world.

Now there are something like a dozen short stories and a handful of novels to the Celestial Empire, with more on the way. I’ve written about other worlds from time to time (including our own, on rare occasion), but the place to which I return most often is the Celestial Empire. I suppose the moral to the story is that you should be careful what you cook up on plane flights, since you might end up involved with it for years afterward. Which isn’t much of a moral, I’ll admit, but what can you expect from someone who creates worlds by accident?

Ellen Klages

SINGING ON A STAR

I

’m spending the night with my friend Jamie, my first sleepover. She lives two doors down in a house that looks just like mine, except for the color. I’m almost six.

’m spending the night with my friend Jamie, my first sleepover. She lives two doors down in a house that looks just like mine, except for the color. I’m almost six.

My father walks me over after dinner, carrying my mother’s brown Samsonite travel case. Inside are my toothbrush, my bear, a clean pair of panties (just in case), and my PJs with feet. I am carrying my Uncle Wiggly game, my favorite. I can’t wait until she sees it.

Jamie answers the door. She has no front teeth, and her thick dark hair is held back by two bright red barrettes. My hair is too short to do any tricks. Her mother, Mrs. Galloway, comes out from the kitchen wearing an apron with big daisies. The air smells like chocolate. She says there are cookies in the oven, and we can have some later, and my doesn’t that look like a fun game! My father pats me on the shoulder and goes into Mr. Galloway’s den to have a Blatz beer and talk about baseball and taxes.

There is only a downstairs, like our house. Jamie’s room is at the end of the hall. It has pale pink walls and two beds with nubbly green spreads. Mrs. Galloway puts my suitcase on the bed next to the window, where Jamie doesn’t sleep, and says she’ll bring us some cookies in a jiffy.

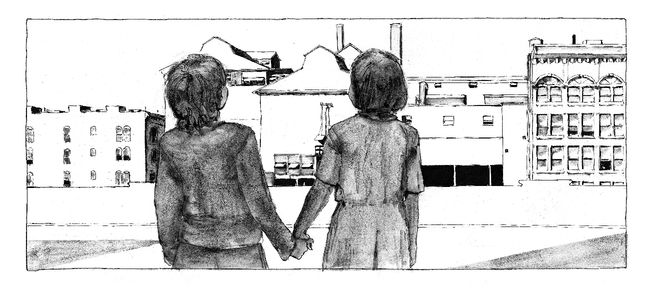

I know Jamie from kindergarten. We are both in Miss Flanagan’s afternoon class. We share a cubby in the cloakroom, play outside with chalk and jump ropes, and are in the same reading circle. This is the first time we’ve been alone together. It’s her room, and I don’t know what to do now. I put Uncle Wiggly down on the bed and look out the window.

It’s not quite dark. The sky is TV blue, and if I scrinch my neck a little, I can see the edge of the swing set in my own backyard. I feel a little less lost.

“It’s time to listen to my special record now,” Jamie says. She holds up a bright yellow record, the color of lemon Jell-O. I can see the shadows of her hands through it.

She opens the lid of the red-and-white portable record player on her bookshelf. I’m jealous; I’m not allowed to play records by myself yet, because of the needle. Jamie plunks it down on the spinning disk, and the room fills with the smooth crooning of a man’s voice:

You can sing your song on a star,

Take my hand, it’s not very far.

You’ll be fine dressed just as you are . . .

Take my hand, it’s not very far.

You’ll be fine dressed just as you are . . .

“We have to go before the song ends,” Jamie says. “So we can see Hollis.”

Jamie is not this bossy at school. I nod, even though I don’t know who Hollis is. Maybe it’s her bear. My bear’s name is Charles.

Jamie points to a door in the pale pink wall, next to my bed. “We have to go in there.”

“Into the closet? Why?”

“It’s only a closet sometimes,” Jamie says, as if I should know this. She opens the door.

Inside is an elevator, closed off by a brass cage made of interlocking

X

s.

X

s.

“Wow.” I have never been in a house with an elevator before.

“I know,” says Jamie.

She pushes the cage open, the

X

s squeezing into narrow diamonds with a creaking groan. “C’mon.”

X

s squeezing into narrow diamonds with a creaking groan. “C’mon.”

My stomach feels funny, like I have already eaten too many cookies. “Where are we—?”

“Come

on

,” says Jamie. “The song’s not very long.” She grabs the sleeve of my striped shirt and tugs me through, pulling the brass cage closed again behind us. To the right of the door is a line of lighted buttons, taller than I can reach. Jamie presses the bottom button,

L

.

on

,” says Jamie. “The song’s not very long.” She grabs the sleeve of my striped shirt and tugs me through, pulling the brass cage closed again behind us. To the right of the door is a line of lighted buttons, taller than I can reach. Jamie presses the bottom button,

L

.

A solid panel slides in front of the brass cage, shutting us off from the room with the pink walls. There is a clank, and a whirr of motor. I close my eyes. The elevator moves.

In a minute, it stops with another clank and the rattle of the brass cage squeezing open.

“Hi, Hollis,” says Jamie.

“Why, hello Miss Jamie,” a voice answers. “What a delightful surprise.” It is an odd voice, soft and raspy, a bit squeaky, like a not-quite-grown-up boy. I open my eyes.

I don’t know where we are. Not in Jamie’s house. Not anywhere in our neighborhood. Outside the elevator is a tall room with a speckled linoleum floor and a staircase with a wooden railing, curving up and out of sight. A rectangle of sunlight slants across the tiles.

I remember my swing set in the almost-dark. I feel dizzy.

“C’mon,” says Jamie. She tugs at my sleeve again. “Come meet Hollis.”

I step out of the elevator. The room smells old and dusty, with a sharp tang, like they forgot to change the cat box. At first I don’t see anyone. Then I notice a little room under the stairs. The floor inside is bare wood, and a man is sitting on a folding chair, reading a magazine with a flashy lady on the cover.

“Two surprises!” says the man. “What a great day this is turning out to be.” He smiles as he closes his magazine, but his voice sounds sad, as if he’s about to apologize.

“This is my friend Becka,” Jamie says. “She’s very good at jacks.”

“A fine skill, indeed,” Hollis says. “I’m pleased to make your acquaintance.”

“Me, too,” I say.

I’m not sure I mean it.

Hollis looks as odd as his voice sounds. He is not young, and is very thin. The skin under his eyes droops like a blood-hound. His hair sticks out in tufts around his head, like cotton candy, but the color of ginger ale. He’s wearing gray pants and a red jacket with a bow tie. On the pocket of his jacket is a black plastic bar that says HOLLIS in white capital letters.

“I want to go up to the roof today,” says Jamie. “Will there be trains?”

“A most excellent question,” Hollis says. “Let me check the schedule.” He pulls back his cuff and looks at his wristwatch. The face is square and so yellowed I can’t see any numbers. “Yes, just as I thought. Plenty of time before the next arrivals. And a good thing, too. I’m feeling a bit peckish.”

I don’t know that word, but Jamie laughs and claps her hands. “I was hoping you were,” she says. “But—” She shakes her head. “But you can’t leave your post.”

“No,” he says, even more sad than before. He looks around the empty lobby like he expects someone to appear. “No, I can’t leave my post.”

“I could go,” Jamie says. She sounds as if she just thought of it. But I think they are telling each other an old joke, one I don’t know.

Hollis snaps his fingers. “Why, yes you could. You’re a big girl.” He turns to me. “Are you a big girl, too?”

I don’t feel very big at all. Too much is happening. But I hear my own voice, telling my mother, “I’m a big girl now,” when she didn’t think I was old enough for a sleepover. “Yes,” I say, louder than I mean to. “I’m a big girl.”

“So you are,” says Hollis. “So you are.” He pulls a green leather disk out of his pocket, about the size of a cookie, with the top all folded over itself, and pinches the bottom. The folded parts open like a flower. When he holds it out to Jamie, I see that it’s a coin purse. Jamie takes out two nickels.

“And one for your friend,” Hollis says. He holds the purse out to me, and I take a coin. The leather petals refold around themselves.

“The usual?” asks Jamie. She sounds much older here.

“But of course,” he says. “Farlingten’s best.”

Jamie leads the way. The front door of this building is glass and wood, with a transom tilting in at the top. I’ve never seen one before, but I hear the word in my head.

Transom.

I say it under my breath, and I can taste it in the back of my throat. I’ve never tasted a word before. I like that.

Transom.

I say it under my breath, and I can taste it in the back of my throat. I’ve never tasted a word before. I like that.

Out on the sidewalk, a white-on-black neon sign buzzes above our heads and stretches halfway up the tall brownstone building. HOTEL MIZPAH. WEEKLY RATES

.

This is a noisy place. Cars and trucks honk their horns under the viaduct, and men are yelling about money at a bar next door. I hear a clang and turn to see a green streetcar clattering down tracks in the middle of the street, sparks snapping from the wires overhead. The lighted front of the car says FARLINGTEN.

.

This is a noisy place. Cars and trucks honk their horns under the viaduct, and men are yelling about money at a bar next door. I hear a clang and turn to see a green streetcar clattering down tracks in the middle of the street, sparks snapping from the wires overhead. The lighted front of the car says FARLINGTEN.

“What’s Farlingten?” I ask Jamie.

“It’s where we are, silly.”

“Where are we, though?”

She huffs a sigh and puts her hands on her hips. “In

Far

lingten.” She seems to think this is enough of an answer and skips a step ahead of me.

Far

lingten.” She seems to think this is enough of an answer and skips a step ahead of me.

I want to go home. I don’t know how to get there from this street.

My neighborhood has trees and front yards and drive-ways and grass. Here all I can see is dirty bricks and stone buildings, black wires crisscrossing everywhere. We come to the corner of the block. Above a wooden rack of magazines and paperback books is a faded green awning that says SID’S NEWS.

Other books

Legacy of Lies by Elizabeth Chandler

Wings of Darkness: Book 1 of The Immortal Sorrows Series by Sherri A. Wingler

Love's Guardian by Ireland, Dawn

A Wild Fright in Deadwood (Deadwood Humorous Mystery Book 7) by Ann Charles

Full Position by Mari Carr

Miss Silver Comes To Stay by Wentworth, Patricia

Alchymist by Ian Irvine

Things Too Huge to Fix by Saying Sorry by Susan Vaught

Summer Camp Adventure by Marsha Hubler

Murder in Bollywood by Shadaab Amjad Khan