Firebirds Soaring (35 page)

Authors: Sharyn November

“What do I have to do?” he asked, very quietly, then she pulled his hand and for a moment he felt himself falling.

It was a little while before anyone noticed he had gone, and by then nobody remembered seeing the two cats slipping away between the tables, one grey and one a long-haired black with big green eyes.

JO WALTON

is the author of four fantasy novels, including the World Fantasy Award-winning

Tooth and Claw,

and

Lifelode

. She has most recently written the Small Change trilogy (

Farthing

,

Ha’penny

, and

Half a Crown

).

Farthing

was nominated for the Nebula, John W. Campbell Memorial, and

Locus

awards. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal, where the food and books available are more varied.

is the author of four fantasy novels, including the World Fantasy Award-winning

Tooth and Claw,

and

Lifelode

. She has most recently written the Small Change trilogy (

Farthing

,

Ha’penny

, and

Half a Crown

).

Farthing

was nominated for the Nebula, John W. Campbell Memorial, and

Locus

awards. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal, where the food and books available are more varied.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I’m remarkably fond of this story. I don’t write much short fiction, but the first part of this one came to me all as a piece in the middle of the night. I got up and wrote it down, and then the next morning I looked at it, wondering what on Earth I’d fished up and whether I ought to toss it back. Sharyn thought it wasn’t long enough, and of course she was right. That’s why she’s a great editor. Thinking about that led me to the other two parts, which now seem inseparably part of the story.

It’s a very unusual story for me. The people have no names—and normally I’m all about the names. Yet the people and the twilight location have a solidity that’s all about objects. I don’t think I’ve ever written anything with so many lists in it—or lists of such strange things. It’s all about provenance, where things and people come from, what stories they are part of. It’s a fairy story that questions the demands that stories make of their protagonists. Like most fairy tales it’s liminal, it’s all about edges and thresholds and twilight and possibilities. But really, for me it’ll always be the story that made me sit up in bed and say the first line aloud to my husband, then rush off to the computer to write it down. Months after finishing it, I re-read Pamela Dean’s

The Secret Country

and discovered with a surprise where the two rhymers and the handful of moonshine had come from. Thank you, Pamela, for such a compelling image that snagged in my subconscious that way.

The Secret Country

and discovered with a surprise where the two rhymers and the handful of moonshine had come from. Thank you, Pamela, for such a compelling image that snagged in my subconscious that way.

Carol Emshwiller

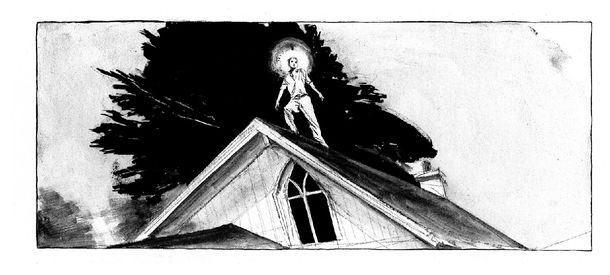

THE DIGNITY HE’S DUE

T

he king’s music will have lots of trumpets and drums, a slow pace so the king can keep his dignity.

he king’s music will have lots of trumpets and drums, a slow pace so the king can keep his dignity.

There’ll be handmade lace at his throat.

On the royal barge he’ll be protected from the sun by a silk canopy. There’ll be another barge for his orchestra. Do not listen. The music is for his ears alone.

The royal picnic will be caviar and white truffles and wild strawberries no bigger than pearls.

But little acts of kindness—that’s how we live now. We always say thank you, though we don’t mean it. Who should people give things to, if not to us? Who better deserves a meal and a dollar? Mother says it’s our due and we shouldn’t be ashamed.

Or we steal. Mother says it’s like taxes—they owe us. We have a little tent that just fits the three of us, me and Mother and my little brother. I and Mother carry big packs. My little brother isn’t supposed to carry anything. That’s because he’s heir to the French throne. Mother thinks he’s fourth in the line of succession. Of course there is no French throne anymore. Mother says that doesn’t matter, we’re still royalty.

Mother says trumpets should sound. She goes

“Toot, dee-dee toot, dee-dee toot”

as a fanfare. (When he was little he liked it, but not anymore.) Mother says music should be written just for him and, she says, might be one of these days when people realize. She says, “Look at his silky black hair and blue . . . so blue, blue eyes. Look at his nose, already aristocratic even at his age. Can he be other than a prince? ”

“Toot, dee-dee toot, dee-dee toot”

as a fanfare. (When he was little he liked it, but not anymore.) Mother says music should be written just for him and, she says, might be one of these days when people realize. She says, “Look at his silky black hair and blue . . . so blue, blue eyes. Look at his nose, already aristocratic even at his age. Can he be other than a prince? ”

(I have blue, blue eyes, too, and silky hair, but nobody cares.)

It’s important that he dress as a prince, but we don’t have anything but hand-me-downs. It makes Mother feel bad to dress him in T-shirts and jeans.

I keep telling her there is no king of France and it is unlikely there will be one ever again. But she says, “Things change. Who knows what’s going to happen? Certainly not you.”

I may be only fourteen, but I think I know more about it than she does.

One time when Mother was away, I cut his hair. At least he’s a happy prince now, with a real haircut. He hated that pageboy. When Mother came back she was furious. “How could you? I don’t want him to look like everybody else. Who’ll know now? Once it grows out again, don’t you dare.”

“He wanted me to.”

“A prince never gets to do what he wants. He has to learn that.”

Mother wants to keep him, as she says, “pure.” What she means is, no scars, neither mental nor physical, but it’s too late. He slams around, climbs things. Already there’s a C-shaped scar on his cheek and the marks of the stitches. And as to his mind . . . for heaven’s sake, how can he be a normal anything? Though she doesn’t want normal.

Mother is teaching him all the things a king needs to know. Especially a French king. History of France: the departments, the châteaux, the rivers . . .

“La douce France,”

she says. “Never any trees this big. You can walk from one village to another. Every house has a wall around it.” But she hasn’t even been there.

“La douce France,”

she says. “Never any trees this big. You can walk from one village to another. Every house has a wall around it.” But she hasn’t even been there.

I’m teaching him other things, like the states right here, the battles that took place in these hills, and, as we go south, slavery. I think a prince should know about slavery. Not that I know much about anything. Still, I did have a chance to go to school for a little while—until our father left us. I was allowed to mingle with the “rabble.” That’s because I didn’t matter.

When my brother says, “

I’m

a slave,” I say, “All children are slaves to their parents, but this won’t last forever,” and he always says, “I could be dead before it ends,” and I say, “The way you slam around, that’s probably true.”

I’m

a slave,” I say, “All children are slaves to their parents, but this won’t last forever,” and he always says, “I could be dead before it ends,” and I say, “The way you slam around, that’s probably true.”

The older he gets, the more he understands that this isn’t the way most children live.

We often sleep in a park, though there’s always a cop comes in the middle of the night to tell us to move on. Mother says, “Keep your dignity. Remember,

noblesse oblige

.” We just pack up and head . . . maybe for another park, if we’re in a town, that is. In the country, woodsy spots are good stopping places. Hardly anybody bothers us there.

noblesse oblige

.” We just pack up and head . . . maybe for another park, if we’re in a town, that is. In the country, woodsy spots are good stopping places. Hardly anybody bothers us there.

We’re safe for a while now, because Mother has us off on the Appalachian Trail. (Yet again.) When you don’t have things to wear to keep warm, you need to follow the birds. We hardly ever have good shoes, and with all this walking, they’re always worn out. Mother found me hiking boots that were set out in the garbage. They were already worn out when she found them.

Mother is happiest when we get, as she says, our due. Now and then we do. My brother gets the most. People think he’s cute. (Mother hates cute. She keeps at him to stand up straight and hold his head high. She tells him, “Don’t be cute,” and, “Stop smiling. Don’t gesture needlessly. Don’t put your hands in your pockets. Look people straight in the eye.”) She sprinkles her talk with French words. “

Alors,”

and

“Mon Dieu.” “Ah, la voilà.” “Venez mes enfants

.” But sometimes I wonder just how good her French is.

Alors,”

and

“Mon Dieu.” “Ah, la voilà.” “Venez mes enfants

.” But sometimes I wonder just how good her French is.

We often hike this trail, going south in blueberry season or going north when fiddleheads pop up. We like it when we see a big rock we remember from the trip before or a gnarled tree we camped under on our last trip. And then there are the lean-tos all along the way. We steal from campers. They don’t expect robbers way out there. We never take their cameras or field glasses or bird books. Mostly we take food and sometimes socks and warm underwear.

Here I am, thinking

we

, as if I agreed with Mother—as if I considered myself part of all this, though I guess, in a way, I am. I have to be. I don’t know how Mother would get along without me. I think I’m in charge. Not of where we head or when, but I keep us out of trouble. And I try to add a little bit of a more normal life to my poor brother’s.

we

, as if I agreed with Mother—as if I considered myself part of all this, though I guess, in a way, I am. I have to be. I don’t know how Mother would get along without me. I think I’m in charge. Not of where we head or when, but I keep us out of trouble. And I try to add a little bit of a more normal life to my poor brother’s.

I’m going to try and stop this. I want us to find a permanent place to live. A nice little town where it never gets too cold, but big enough for us to hide in.

I’ll have to break it to Mother that we aren’t going to live this way anymore. I don’t know what she’ll do. Maybe I won’t be able to stop her. If she and my brother take off alone, I’ll have to follow.

Napoleon Gustave Guillaume Williamson. We don’t even have a French last name. Did my father approve of that name for his son? Or did Mother change it after my father left us? I wonder that she hasn’t changed our last name.

He, Guillaume, was all right with this kind of life until last year, when he turned nine. He’s getting too smart to put up with it. I tell him not to worry, I’m going to get us out of this, but I have to find the right place and I have to do it in a way that Mother won’t object to too much—if that’s possible.

He won’t put up with this much longer. We’re all right now, though. He likes being out on the trail like this. And he likes campers’ kind of food, even the dried stuff. He likes the whole idea of the Appalachian Trail. He loves watching animals and bugs and such. He even loves spiders. Can a prince be interested in spiders?

I try to make him part of my plans, so he’ll feel he’s working on getting us out of this, too. I tell him to think about the kind of town he wants to live in and when we come to towns he should look around and see if this is the one. I hope that’ll keep him from being too impatient.

But things change before I’m ready. It starts when Guillaume tells us he wants to be called Bill.

Mother has a fit. Worse than when I cut his hair. I’ve hardly ever seen her this angry, and usually it’s me she’s mad at.

It’s a good thing we were out on the trail at the time. Mother made a terrible racket. After she calmed down, I noticed there wasn’t a sound anywhere, the birds were quiet, no rustlings from ground squirrels, even the bugs were quiet. Guillaume . . . Bill and I were quiet, too.

I think that made him realize things he hadn’t before, and it must have made him angry, too. I guess he decided he wouldn’t wait for my help.

The king’s crown will be heavy.

His robes will sweep seven yards behind him. If he

turns too fast they will trip him.

Lights will be lit all along the roads he’ll travel.

Lots of places along the trail, you have to pass through little towns to get from one edge of the trail to the other. In this town the trail goes right along Main Street. There’s a play-ground in the middle. Mother leaves us there while she goes off to scrounge. She’s so angry she hasn’t said a word since our fight yesterday—not really a fight because Guillaume . . . Bill and I just stood there watching. I’m worried about her. I think to follow her, but I know I should take care of Bill.

I practice calling him Bill a few times (every time I do, he smiles), then I stretch out on a bench to take a nap and . . . Bill . . . goes off to look for bugs or, if he’s lucky, there’ll be a stray dog. I’m tired. None of us slept too well after that “brouhaha” (Mother’s word) about Bill’s name.

Mother kept waking us up with one more thing—one more reason why Guillaume needs to be

Guillaume

. She can hardly bring herself to say

Bill

even just to talk about it. She spits it every time she says it.

Guillaume

. She can hardly bring herself to say

Bill

even just to talk about it. She spits it every time she says it.

I didn’t think he’d go off without me. But maybe he found this was a town he liked, though it’s a little small for my taste—for hiding in, that is. I’m sure it’s small for Mother’s taste, too. She doesn’t think he’d ever get his due in a small town. The only museum is the Indian museum. Mother says, “A prince must be cultured. Must have a real education: politics, philosophy, and all the arts, too.” Mother worries that he’s into bugs.

I was afraid this would happen, especially after the Bill episode. I feel really bad. I always thought we were in this together.

For all I know, Bill is back on the trail beyond the town, but without a tent? He didn’t even take his raincoat.

Mother is counting on his ignorance. “After all,” she says, “he’s only nine. He can’t get far.” But almost-ten-year-olds are smarter than people think.

She says, “This is all your fault. You should have been watching.”

I tell her he’ll just keep running away if our life keeps on as it is. He won’t put up with it anymore, and especially he won’t if she doesn’t call him Bill.

“I won’t call him . . .” She can’t even say it.

But suddenly she thinks he’s been kidnapped. She says, “It’s not about that awful name at all, it’s that he’s so beautiful, how can he not be kidnapped?”

Other books

The Post-Birthday World by Lionel Shriver

Secret Brides [3] Secrets of a Scandalous Marriage by Valerie Bowman

When Harlem Nearly Killed King by Hugh Pearson

DarkestSin by Mandy Harbin

Wedding Girl by Madeleine Wickham

Memory in Death by J. D. Robb

Split Infinity by Piers Anthony

The Know by Martina Cole

Intellectuals and Race by Thomas Sowell

The Protea Boys by Tea Cooper