Fighter's Mind, A (12 page)

Authors: Sam Sheridan

But it needs to be tempered with humility outside the ring or the cage. You have to learn from everyone; if you aren’t growing you’re dying. BJ Penn, the “Prodigy,” will sometimes roll with white belts and analyze the awkward, new positions they end up in—not that they’re necessarily good ones but there might be something in it. All of the best grapplers have become eternal students, even the

mestre

. Perhaps it is this need that makes great fighters humble: they’ve been forced to learn it, from the very start, to become great.

mestre

. Perhaps it is this need that makes great fighters humble: they’ve been forced to learn it, from the very start, to become great.

Marcelo, when he said “I just love it more,” was giving me the secret that there is no secret. His strength was in his joy in the game.

FRIENDS IN IOWA

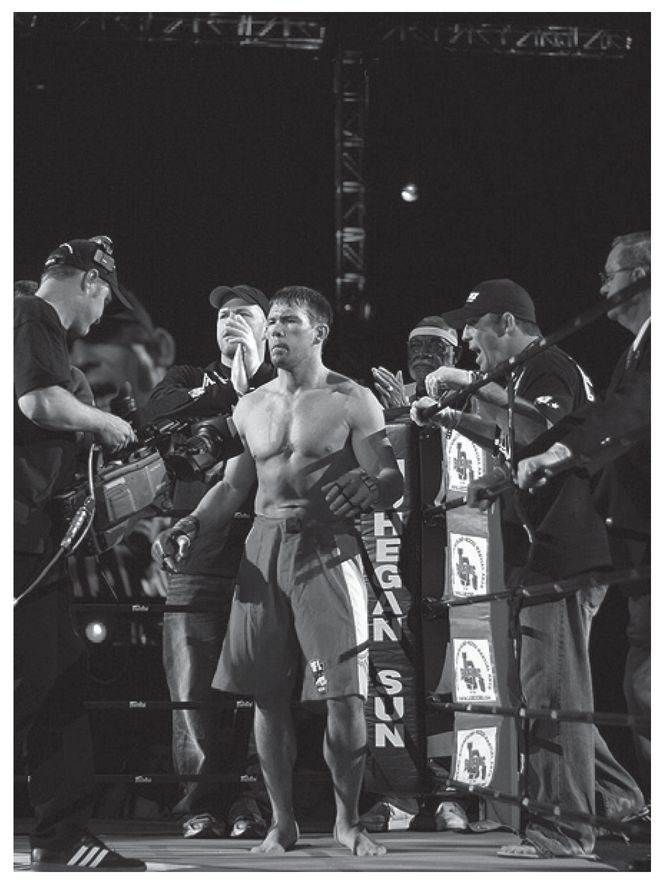

Rory Markham and Pat Miletich prepare for Rory’s fight against Brett Cooper. (Courtesy: Zach Lynch)

It’s easy to do anything in victory. It’s in defeat that a man

reveals himself.

reveals himself.

—Floyd Patterson

My introduction to MMA was a rude one, chronicled in

A Fighter’s Heart.

I went out to Pat Miletich’s gym in Bettendorf, Iowa, to train and fight an amateur MMA fight and write an article for

Men’s Journal

. I ended up getting the snot kicked out of me on dozens of occasions.

A Fighter’s Heart.

I went out to Pat Miletich’s gym in Bettendorf, Iowa, to train and fight an amateur MMA fight and write an article for

Men’s Journal

. I ended up getting the snot kicked out of me on dozens of occasions.

The choice of gym was an easy one. I chose Miletich because of his reputation. Pat is the prototype for the modern MMA fighter, one of the first champions who could do everything. Most fighters of his day (the early, below-the-radar days of MMA in the United States in the mid to late 1990s) were one thing or another—either they were strikers or they were grapplers. Pat was the first guy who could do it all; he had submissions, great takedowns, he moved like a pro boxer, and he knocked guys out with head kicks. He was balanced and this led him, eventually, to the top. He was a five-time UFC champion at 170 pounds, but this was during the “dark days” of the UFC, when the promotion nearly slipped into oblivion. He had many of his early fights in the days before weight classes.

Pat made his bones as a coach. He is on the short list of best MMA trainers in the world. His camp, called Team MFS (Miletich Fighting Systems), was the dominant camp in the sport over the past ten years, with at times three UFC belt holders on the mats. It became a self-fulfilling prophecy—all the best guys were training with Pat, so everybody wanted to come train with Pat. Even in the modern MMA world, with the explosion of huge, stacked fight camps, Team MFS is still in the top tier.

In the early days of MMA the fight camps were filled with tough guys and infamous for the beatings and hazings. The Lion’s Den, Ken Shamrock’s gym, was well known for it, as was Chute Boxe in Brazil; guys who wanted to train had to survive vicious beatings and absurd workouts. MFS in Bettendorf was always the real deal, a place where anybody who showed up would get the living shit kicked out of him for weeks and months on end, but it wasn’t hazing. That was just life at MFS. A great part of the success of the camp has to be attributed to that intensity, the highly charged atmosphere that Pat created by combining all the insanity of wrestling workouts with the damage and viciousness of hard boxing sparring.

I’ve written a lot about Pat, and we’ve gotten to be friends, which makes me feel like A) I’ve said it all before and B) I don’t see him so clearly. Pat’s a good guy and a good friend. He’s funny, friendly, maybe a little burned out after so many years and so many champions, but he’s still scheming. He’s a fighter, and a freakishly tough human being. I’m plagued by a recurring rib injury, but when I cry off a sparring session Pat never believes me—he thinks I’m being a big baby and he suspects malingering. In his whole career, street fights included, he’s never been put down from a punch to the head.

I remember Freddie Roach saying that great fighters are “special people,” by way of an excuse for any silliness, any diva behavior or eccentricities. Freddie was talking about James Toney. But it’s true with a lot of great fighters—you can hem and haw, say this and that, but they’re just stronger, denser, tougher, and faster. People talk about Rodrigo Nogueira’s otherworldly grip strength, or how Fedor Emelianenko’s bones seem to be much heavier and thicker than normal, or how Randy Couture’s lactic acid levels drop when he’s exerting himself during a choke. Pat’s like that, he’s special. As Jon Wertheim documented so well in

Blood in the Cage,

there really is a “cult of Pat” in the gym: he’s charismatic, funny, and maybe a little crazy.

Blood in the Cage,

there really is a “cult of Pat” in the gym: he’s charismatic, funny, and maybe a little crazy.

When I arrived at MFS in ’04, another young fighter had made the move out from Chicago to give professional MMA a shot, a twenty-one-year-old kid named Rory Markham. Rory was powerful, with all-American GI Joe looks and an explosive boxing style. He had the same sense of humor as I did, and we got to be friends.

Rory’s clean-cut looks were marred only by his hands, which were stubby and white with scars. He’d been a very serious street fighter in high school on the South Side of Chicago. He told me he dutifully went out and got in a fight every Friday and Saturday night for about two years straight. He’d been obsessed with fighting from an early age, and he had his share of demons hidden under a layer of gregarious ease.

Over the years we kept in touch, and sometimes I went to see his fights. He was a big 170-pounder, having to cut from 195 or more, and the first few cuts were tough on him. Rory started as a striker, pure and simple, a banger who nearly always had to eat a few to give a few—but Rory had a good chin that he trusted. He loved to fight, to get in there and mix it up. Still, the more we talked, the further his career went, the more he started to think about the rest of the game. He took a loss here and there, which gave him pause. When he looked at the top of the division, the monsters up there, he knew his physical gifts and striking weren’t enough, because those guys could do everything. Rory was a talented, tough fighter but right on the edge in terms of natural gifts. He was fast, strong, and tough enough to blow through most guys in the bottom or middle tier, but he was well aware (from sparring at Pat’s over the years) that he wasn’t going to be able to do that with the best guys in the world. He had trouble with head movement; he would do it religiously during shadow boxing but almost never during a fight, nearly always getting tagged a few times. Still, even though he knew better, his evolution as a fighter continued mostly in one direction, striking. It was what he loved.

The New England winter afternoon was already growing dark as I boarded the bus to Mohegan Sun. It was the now defunct International Fight League’s (IFL) Grand Prix, the end-of-the-year event. I was there for a few reasons—it was close by (I was wintering in Massachusetts), Pat was there, and Rory was fighting on the undercard.

I got on the bus with Pat, Rory, his assistant coach Steve Rusk, and L. C. Davis, his fighter at featherweight who would be competing later for the title. The bus rolled away into the darkness and I was struck by how much MMA history was on board—along with Pat, Zé Mario Sperry, Randy Couture, Carlos Newton, Frank Shamrock, Matt Lindland (Bas Rutten and Renzo Gracie would show up later)—all giants of MMA, all disowned or persona non grata with the UFC, which was having a competing event that night, to which we stood a distant second. Pat, in particular, was feeling the sting as Matt Hughes, his former protégé, was fighting for his career in the main event at the UFC. Both Matt and Robbie Lawler had left Pat for lucrative offers to start up their own gym, and Robbie had been like a son to Pat.

Rory claimed to be feeling good; he was ready and anxious to get this over with. He was fighting second, which was early for him. His opponent, Brett Cooper, was an unknown. Nobody knew anything about him. That happened frequently in MMA, though less so at this level, but it always made me uneasy. Rory had made weight. He’d done an hour and a half workout the day before, the morning of weigh-ins, which sounded funny. Wasn’t that a little long? I thought the whole point was to sauna and sweat it out, that last seven pounds of water, without exercising and burning into your reserves. But these guys were professionals and I was sure they knew what they were doing.

Mohegan Sun is a good venue, with steep walls that pack the crowd in around the ring, and it was a full house. Brett Cooper looked small—he’d weigh in at 168, whereas Rory made 170 but put at least ten pounds on overnight—yet he was determined; he had his game face on and long shaggy hair. Pat wanted Rory to jump all over him. To start fast.

When the bell rang Rory went right to him, and Brett, being a little longer, caught him right off the bat. That is standard for his fights—Rory always gets hit. He dug down and started banging. Rory has real power and quickly he had Brett hurt. He even caught him with a head kick. The crowd yelled and it looked all over. Rory tried to finish, but he “fell in” on top of his punches, he got too close, fell into a clinch, and Brett managed to take Rory to the ground. Brett was buying himself valuable recovery time. Rory slipped on a triangle from the bottom, a basic choke (catching the opponent and choking him in a triangle between your legs and one of his arms). He nearly had it—they fought in that triangle for what felt like ten minutes. It looked like it was over, the triangle was on so tight. But Brett didn’t tap. Finally, Rory gave it up. He thought about a transition to an armbar, but he didn’t believe in it himself. It was half-assed, and Brett pulled out easily. The fight went back and forth briefly before the round ended. Rory, in the corner, was bleeding from several small cuts—but then he always is.

In the second round, Brett was still pretty game and he caught Rory a couple of shots, a grazing knee, and then Rory covered up and ate an uppercut and went down, stunned. Brett leaped in to finish. That was it. The ref waved it off. Rory was TKO’d.

Contrary to popular belief, the first thing, the very first thing a fighter sometimes feels upon losing is relief. It’s over. The stress, the hatred, the desperate battle for survival—it’s finished. “When you’re knocked down with a good shot you don’t feel pain,” Floyd Patterson, the “Gentleman of Boxing,” once told the

Guardian

journalist Frank Keating. Floyd had been the heavyweight champion after Rocky Marciano retired (he’d beat Archie Moore for the interim title) in 1956, and was almost too nice a guy for it.

Guardian

journalist Frank Keating. Floyd had been the heavyweight champion after Rocky Marciano retired (he’d beat Archie Moore for the interim title) in 1956, and was almost too nice a guy for it.

“Maybe it’s like taking dope. It’s like floating. You feel you love everybody, like a hippie I guess,” said Floyd.

I remember seeing Anderson Silva lose to Ryo Chonan, and seeing the smile of relief on Anderson’s face backstage. I’ve seen that relief gradually giving way to grief, as the fighter comes to grips with months of life feeling wasted, of the career and financial implications. “The fighter loses more than his pride in the fight; he loses part of his future. He’s a step closer to the slum he came from,” Patterson also said. Floyd lost a few of his biggest fights under intense national scrutiny, and once he even wore a disguise—a wig and fake beard—in order to get out of the stadium unseen after a loss.

The fighter has lost a part of himself, the part that believed in his own power and invincibility—because what a fight is about more than anything else is will. When you’re knocked out, I can do whatever I want to your unconscious body. Your ability to make decisions, to master your own fate is destroyed when you lose a fight. You’ve been dominated, and to a male of the species there is nothing worse. It violates every genetic principle in your body.

Kelli Whitlock Burton and Hillary R. Rodman wrote an essay entitled “It’s Whether You Win,” for a book called

Your Brain on Cubs,

about the psychological underpinnings of baseball and fandom. They discuss experiments with lab rats that showed a male being defeated by another male actually has permanent changes in his brain. “Evidently, social defeat is highly effective in producing a state analogous to psychological pain,” they wrote. “Social defeat sets in motion a number of brain processes that lead to increased sensitivity to subsequent stressful experiences . . . the hippocampus actually changes after repeated defeat experiences . . . the hippocampus is well known to be crucial for the formation of memories of specific experiences . . . in addition, the hippocampus is one of the few structures that make new nerve cells in adulthood.” The research shows that repeated social defeats not only can affect the hippocampus’s ability to make new cells, it affects serotonin levels and is probably linked to depression.

Your Brain on Cubs,

about the psychological underpinnings of baseball and fandom. They discuss experiments with lab rats that showed a male being defeated by another male actually has permanent changes in his brain. “Evidently, social defeat is highly effective in producing a state analogous to psychological pain,” they wrote. “Social defeat sets in motion a number of brain processes that lead to increased sensitivity to subsequent stressful experiences . . . the hippocampus actually changes after repeated defeat experiences . . . the hippocampus is well known to be crucial for the formation of memories of specific experiences . . . in addition, the hippocampus is one of the few structures that make new nerve cells in adulthood.” The research shows that repeated social defeats not only can affect the hippocampus’s ability to make new cells, it affects serotonin levels and is probably linked to depression.

Other books

Limit by Frank Schätzing

A Death In The Family by James Agee

Sam in the Spotlight by Anne-Marie Conway

Modern Goddess: Trapped by Thor (Book One) by Odette C. Bell

From the Moment We Met by Adair, Marina

Aris Returns by Devin Morgan

Turn Right At Orion by Mitchell Begelman

Stars Across Time by Ruby Lionsdrake

The Best American Travel Writing 2015 by Andrew McCarthy

Loud Awake and Lost by Adele Griffin