Fighter's Mind, A (7 page)

Authors: Sam Sheridan

“You have to listen to the corner. Think of nothing, listen to my trainer and Philip. They control you to be that way, and the Thai fighter has to be like a robot. I fight you eye to eye, I see you. The cornerman, the third eye, he see everything, he see me and you. The corner change the game.”

The reason for such strict controls over fighters? Jongsanan smiles at the innocence of my question, the naivete.

“Gambling. Ninety-five percent of fans are there for betting, to make money. The fan can make you fight different way. In the U.S. the fan come to support you, to see your skill, to see a show. Over there it’s for betting, and it makes me upset. If muay Thai fighters in Thailand could get respect like here, it would be so good for the Thai boy. But in Thailand they can’t afford the ticket unless for gambling to make the money back.

“If you love muay Thai here, you can be a good fighter. Here they respect you, and nobody will beat you up if you lose. You won’t lose your home, your living, like in Thailand. Here they admire you even if you lose. Seventy-five percent of American fighters survive by themselves. They fire you if you aren’t a good corner. Totally different in Thailand. In Thailand you have to do what corner say, you can’t fight anywhere else. If somebody else wants to train you he has to buy your contract out from me.”

When you watch a muay Thai fight, you become aware of how important composure is. The Thais fight with epic, steely composure, never showing pain or emotion—unless it’s to try and sway the judges. They act with their faces about how they feel the fight is going. It’s almost like soccer players when teams try and draw a foul, or the B-movie acting in the NBA. I asked Jongsanan about it.

“Use face, it comes to the judge—you kick me hard, but I show it’s okay,

maybelai

[the ubiquitous Thai word for “never mind”]. The judge say oh, he’s okay. For the judge, for the system, for the crowd, for you, for the gambling guy.”

maybelai

[the ubiquitous Thai word for “never mind”]. The judge say oh, he’s okay. For the judge, for the system, for the crowd, for you, for the gambling guy.”

“John” Wayne Parr is an Australian muay Thai legend, and he provided more insight into the Thai appreciation for composure. Wayne lived and fought in Thailand from 1996 to 2000, and has since continued his professional muay Thai career. He’s been fighting the best in the world for nine years in Japanese megaevents such as the K-1 Dynamite show. In 1999 he was a rising star, featured in the first kickboxing magazine I ever saw, “on the beach” in Darwin, Australia. I remember the Thai publicity shots of him posing with six-guns, like a cowboy. That same magazine had the advertisement for the Fairtex muay Thai camp, which looked pretty good to me after sailing across the Pacific. He and I discovered each other on Myspace as I was finishing this book, and I asked him about the mental game he’d learned in Thailand.

“The first lesson I learned is never show any emotion while fighting,” he wrote me from Australia. “And if you want respect from the Thai fans, you never give up until the final bell. I’ve seen some Thai boys fight their heart out, for four and a half rounds, getting a sound beating. Then, for last half of the the last round, they stopped fighting and waited till the clock ran out. When we got back to the camp the boys would cop an ear full from the trainers, till the point where they would start to cry. They would be ordered, even though they were busted up, to run and train the next day—because they didn’t deserve a day off until they learned to fight till the end.”

He continued, “If you fight with all your heart, take punishment, get cut yet still manage to wipe the blood out of your eye and keep walking forward, the Thais will accept you as a warrior. It might sound strange, but to have the respect of the Thais is just as important as a win, because they have a very high standard. If they give you the thumbs up you’re halfway there to becoming a champion.”

Wayne told stories of seeing other Westerners come in to Thailand to fight but quail at the first sight of their own blood. Muay Thai utilizes the elbows to attack, and the tip of the elbow can cut like a knife. Many foreigners would fold up their tents when they got cut, but not Wayne.

“I would rather go out with half my face missing, losing the fight, but still getting a pat on the back from the Thais. They would say,

Jai Dee,

or good heart. If you can prove yourself in Thailand, then once you come back home fighting other Westerners feels easy; you have already faced the scariest of scary. There is nothing that they can do that the Thais haven’t done. I fought an English guy in 1998, he cut me five times in five rounds, I ended up with fifty-four stitches after the fight. Not once did I think about giving up; I kept walking forward, applying pressure. I lost the fight but even now I have people coming up to me, saying how they love to play that fight in front of their friends who have never seen muay Thai, to show them what being a warrior is all about.”

Jai Dee,

or good heart. If you can prove yourself in Thailand, then once you come back home fighting other Westerners feels easy; you have already faced the scariest of scary. There is nothing that they can do that the Thais haven’t done. I fought an English guy in 1998, he cut me five times in five rounds, I ended up with fifty-four stitches after the fight. Not once did I think about giving up; I kept walking forward, applying pressure. I lost the fight but even now I have people coming up to me, saying how they love to play that fight in front of their friends who have never seen muay Thai, to show them what being a warrior is all about.”

Back in Boston, Mark and I talked about Thailand. Years ago, I spent six months training in Thailand, and by the end I felt the disconnect between Thai trainers and Westerners. It goes deeper than just language, although that’s a big part of it. The foreigner coming in has a hard time understanding the system, who’s in charge, what it all means. The Thai trainer can’t easily communicate the more complex ideas of timing, breathing, or composure— and they might not anyway. They train together in the ring but watch each other across a cultural chasm. I thought Mark would probably understand this as well as anyone. He speaks fluent Thai and has spent a good portion of his adult life in Thailand.

Mark muses aloud. “It was hard for me, figuring out what makes them tick. I watch Kru Yotong raise everybody, and he’s watching to see who wants to be there. When two little kids argue, they get the gloves put on and go fight five rounds in the ring, with all the adults cheering like crazy. I realized what it’s all about—it’s ranking.” Mark’s face lights up with the remembered revelation.

“When the fighters eat, they eat in order—like a wolf pack. The alpha eats first, the omega eats last. The whole camp is like that. The champs go first, and the little kid who lost, he gets fed last and gets picked on for a few days. The fed stay fed. It’s survival. A lot of those little kids, their parents couldn’t afford them.”

Mark develops this theme, and he’s got a destination in sight. “Kru Yotong takes them in, they don’t have anything else to fall back on. When you have nothing, and then you have a father figure or mentor, and food and training, you become connected to that person. I do the same thing here. After training we hang out, we eat together, our families know each other, they’ve all been to my house and I’ve been to theirs.

Camp means camp

—food, shelter, and fire.”

Camp means camp

—food, shelter, and fire.”

Mark smiles when he says this, for he’s revealed the secret.

“That sense of pride that comes from

camp,

that is really important. There are other factors that are important, too, that are tied to that, like honoring your traditions. Then comes the modern world, which is the business aspect, making money. If my students don’t pay I can’t run this camp. And finally, of course, there’s the primal source in every fighter, gameness. Being cut out to do what you do. But the camp has room for everyone, guys who don’t fight hold pads or find another way to fit in.

camp,

that is really important. There are other factors that are important, too, that are tied to that, like honoring your traditions. Then comes the modern world, which is the business aspect, making money. If my students don’t pay I can’t run this camp. And finally, of course, there’s the primal source in every fighter, gameness. Being cut out to do what you do. But the camp has room for everyone, guys who don’t fight hold pads or find another way to fit in.

“I keep everyone so close to me, that’s what makes me successful. They’re part of a family. A lot of my students here have grown with me. It becomes a passion and makes them stronger. At the end of a hard training session, I have them all walk around with their hand up, because they’re all winners and they’re all MY winners.”

He pauses, thinking long and hard.

“That’s most of it, for a trainer. It’s about building that trust. You don’t marry someone you just met, right? The guys who are around long enough, they trust me because they see what I’m about, for the top guys and the amateurs. A trainer you don’t respect and trust you can’t learn from, so I have to maintain my integrity, you know?”

I asked Mark to elaborate on his game plans, on all the success he was having in the UFC. How was he going about it?

“That trust is crucial if you’re going to have success with a game plan in a fight. Of course, the first thing you got to think about is, Can my fighter listen to a game plan? Can he execute? Or will he be too emotional? Emotional fighters are useless to give game plans to. So are amateurs, someone too inexperienced. They can’t hear you, anyway. So with a guy like that, you don’t even tell him what the game plan is. You just train him so that what he’s doing is the game plan and he doesn’t know it.”

I think it was Cus D’Amato, the legendary boxing trainer, who said, “I get them to where they can’t do it wrong even if they tried,” meaning he would train his fighters to do the right thing until it was instinctual.

“But if a fighter can listen and stay composed, the first step is understanding the opponent. I don’t watch tape over and over, I watch just enough to know what’s happening. You have to go with your gut reaction, the first time you see the fight. Because the more you watch, the more you can convince yourself of something else. You clutter your mind. When I was a fighter, the more tape I watched, the more I’d be surprised by stuff.” Mark breaks into a surprised voice, playing the confused fighter. “He didn’t look like he had power but he hits hard! I never saw him throw a left lead kick but he’s been doing it all night!” He laughs. “So I watch enough tape to get an understanding, then I shut it down.

“With MMA these days, everyone’s traveling. So I find out where he’s preparing, who’s in his camp. Is he in Thailand? Or is he at Team Quest? If everyone at whatever camp he’s at has a great single-leg takedown, we’ll work on defending that.

“Always, there is the individual you’ve got. Like Kenny Florian, he doesn’t do well if you overbuild his confidence. His brother helped me understand that. He relaxes too much. Jorge Rivera is similar, but he’s also nervous, so I keep him relaxed, telling him ‘you’ll kill this guy’ through training so he’ll sleep well and train hard. But then right at the fight I’ll start making him nervous, ‘You better watch out for this guy he’s really tough,’ because Jorge needs that edge.

“I definitely watch the opponent and his trainer on their way into the cage. How smooth are they operating, how relaxed are they? Are they nervous? Where’s the ice? Where’s the mouth guard? Are they fumbling around? Well, if the captain of the ship is a nervous wreck, there’s a problem on board. And the reverse is important. When I come in, it’s like clockwork, everyone has a job, everything is on schedule. I keep it perfectly organized, like feng shui I know where everything is and everything is right. The fighter gets water the second he thinks of it, he gets his mouth guard the second the referee asks for it. He turns to me, and boom, I slide it in. If a trainer doesn’t know something, or is nervous, it’s the beginning of the end, because it will carry over into the fighter. When you see chaos in the locker room that’s a bad sign.

“I still go to a lot of amateur muay Thai fights, and for a guy’s first fight I just make sure he knows it’s a sport. There are people here, this is a controlled environment, he’s not gonna kill you with a knife! In fact, when it’s over, you guys are going to be best friends for about a month.” He laughs. “I’ve just seen it so many times. I tell my first timers, ‘You may hate it or you may love it, but you’ll learn something. It’ll be a great experience.’”

That night we drove through the frozen streets in a caravan to Legal Seafood. I sat between Kenny, Mark, Patrick Cote (a top 185-pounder), and assorted guests. We all listened rapt to Marcus Davis, another UFC professional with a battered friendly face, tell truly terrifying ghost stories. As we ate I felt the warmth of camp all around me.

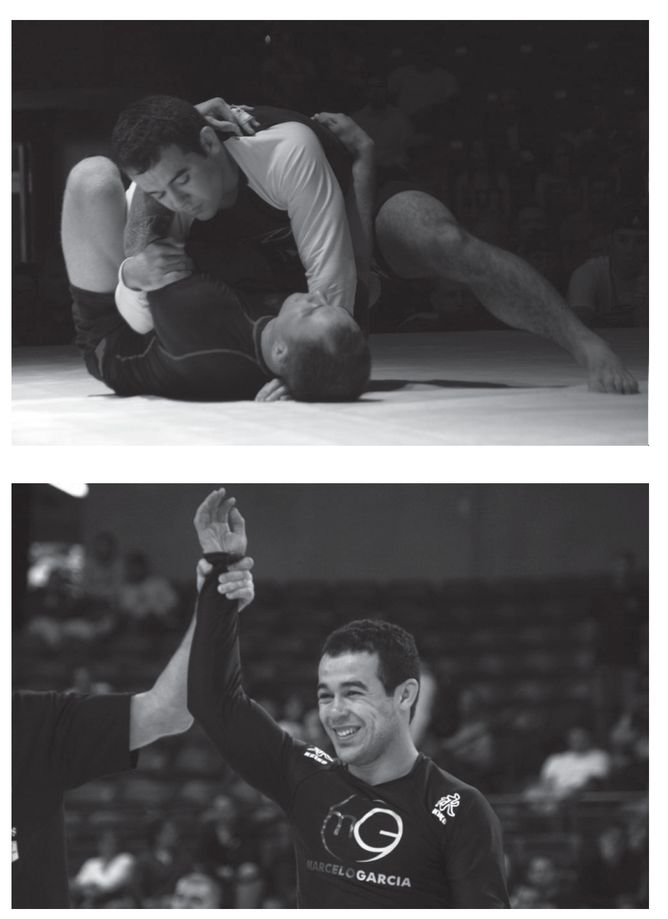

THE KING OF SCRAMBLES

Marcelo Garcia (Courtesy: Marcelo Garcia)

If you continue this simple practice every day, you will obtain

some wonderful power. Before you attain it, it is something

wonderful, but after you attain it, it is nothing special.

some wonderful power. Before you attain it, it is something

wonderful, but after you attain it, it is nothing special.

—Shunryu Suzuki

Mixed martial arts, the modern-day proving ground for hand-to-hand combat systems, introduced ground fighting into the collective conscious. Royce Gracie proved, beyond the shadow of a doubt, that fighters who couldn’t fight on the ground were easy pickings for those who could. He used a family variant of the Japanese martial art

jujutsu,

called Brazilian (or Gracie) Jiu-Jitsu. What the world didn’t know was that MMA fights had been taking place in front of massive crowds in Brazil for fifty years or more, under the catch-all name

vale tudo,

“anything goes.” The Brazilians knew the value of ground fighting, and the Gracie family knew how to take a good striker out of his element. The philosophy has always been a part of fighting—take your enemy from where he wants to be, make him fight your fight.

jujutsu,

called Brazilian (or Gracie) Jiu-Jitsu. What the world didn’t know was that MMA fights had been taking place in front of massive crowds in Brazil for fifty years or more, under the catch-all name

vale tudo,

“anything goes.” The Brazilians knew the value of ground fighting, and the Gracie family knew how to take a good striker out of his element. The philosophy has always been a part of fighting—take your enemy from where he wants to be, make him fight your fight.

Simply put, jiu-jitsu is at the heart of MMA. The art today is essentially interchangeable with submission wrestling, or grappling. At this point it’s semantics, although jiu-jitsu usually includes practice in the

gi.

The

gi

is the white judo kimono and is how jiu-jitsu was originally taught, but in MMA the rules have been changed so the

gi

is not allowed. Fighters learn a style they (inventively) call “no-

gi

.”

gi.

The

gi

is the white judo kimono and is how jiu-jitsu was originally taught, but in MMA the rules have been changed so the

gi

is not allowed. Fighters learn a style they (inventively) call “no-

gi

.”

Other books

Know the Night by Maria Mutch

Rider's Kiss by Anne Rainey

The Man Who Loved Dogs by Leonardo Padura

The Princess is Pregnant! by Laurie Paige

Prince William and Kate Middleton by Chris Peacock

Quarterback's Surprise Baby (Bad Boy Ballers Book 2) by Imani King

Murder Vows (Storage Ghost Murders Book 4) by Larkin, Gillian

Stealing Grace by Shelby Fallon

31 Days of Winter by C. J. Fallowfield

Chains (The Club #8) by T. H. Snyder