Authors: Sergei Kostin

Farewell (41 page)

If such was her intent, it worked wonders, because the KGB, infuriated by the missed opportunity due to the negligence of its surveillance teams, made a last attempt at compromising the DST. Svetlana was dispatched to the French consulate, but the reception was icy. In all likelihood, Golubev had acted out of pique, with no real hope of making up for the missed opportunity. The net result was that Vetrov did not stand a chance to survive.

The investigation was over by the end of April 1984. Vetrov was charged with high treason and intelligence activity in favor of a foreign power. He pleaded guilty. Yet, six long months went by before the trial began. The KGB was waiting for Prévost to contact Svetlana. It did not happen.

Thus, it was not until November 30, 1984, that Vetrov was brought before the Military Chamber of the USSR Supreme Court. The hearings took place in Lefortovo, in the same room where Vladimir and Vladik had seen one another for the last time.

Svetlana was present at one session only. She had come down with pneumonia and was running a high fever. Focusing was difficult. She needed time to think before answering the prosecutor’s or the judge’s questions, anxious not to let slip one word too many.

Vladimir was correcting her, always to his detriment. He was in the same state as he had been in since his return from Irkutsk: cheerful, happy to be there, in court, with a big smile, and joking. Svetlana is convinced that he was drugged then, too. One wonders what would have been the use of it, since the proceedings were behind closed doors.

After her deposition, Svetlana left. A clerk ran after her to let her know that she could visit her husband in one week. Svetlana nodded. She knew the routine.

Those eight days gave her the time to heal. When she saw Vladimir again, the pneumonia was gone.

“I barely recognized you in court,” said Vetrov.

“I believe that. I was constantly on the verge of passing out because of the pneumonia and the rest.”

“Yes, you sure were strange,” agreed Vetrov.

From this conversation with her husband, Svetlana remembered a few more sentences the meaning of which she had not understood at the time.

“I brought you gifts from the camp; I made them myself. Take them with you. And get my suit and my other things back.”

Again and again, Vetrov took her hands in his and kissed them. The three examining magistrates, present during the visit, were bending over to see better. Was he trying to slip a note in her hand?

“You’ll come see me again?” asked Vetrov as they were taking him away.

“Of course I will! As soon as I receive the authorization,” answered Svetlana.

Those were the last words they exchanged.

In the defendant’s last statement, clearly inspired by his lawyer, Vetrov referred to the writer Maxim Gorky, who believed that men were enemies only due to circumstances. He also talked about Raphael and his representation of Justice, resting on fortitude, wisdom, and temperance.

6

He affirmed that he was not a finished man and that, provided his life was spared, his knowledge and experience could still be of use to the State.

This was to no avail. On December 14, 1984, the Military Chamber of the USSR Supreme Court, presided over by Lieutenant General Bushuyev, pronounced sentence: capital punishment, or rather “exceptional” punishment, as per the euphemistic language of Soviet laws.

In January 1985, Svetlana went on an assignment at the Hermitage Museum in Leningrad. All that time, she had kept working at the Borodino Battle Museum. Her colleagues had noticed that her husband was no longer around, neither dropping her off at work in the morning nor waiting for her in the car at the end of the day. To avoid further questions, Svetlana told them that Vladimir had passed away. He had died, she told them, in a tragic accident during a business trip.

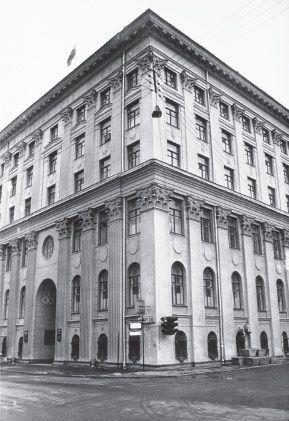

The USSR Supreme Court.

She stayed in Leningrad only three days. On January 25, she came back to Moscow and went to Lefortovo with a parcel for her husband. The clerk gave it back to her. Vetrov was no longer there.

Svetlana called Petrenko, his deputy Shurupov, Sergadeev, and other magistrates, with no answer from anyone. The next day she tried again, to no effect.

Colonel Golubev had given Svetlana his phone number for her to call him in case Jacques Prévost turned up. Not knowing who else to turn to, she called him. Golubev told her to go to the Supreme Court Military Chamber, 15 Vorovsky Street. He gave her the number of the office where she would get explanations.

Svetlana went there immediately. Two strapping men, over six feet six inches tall, asked her to sit down and put a glass of water in front of her. Then, one declared in an official tone that on January 23, 1985, the sentence pronounced by the Supreme Court had been executed. Both men were imbued with a sense of the moment’s solemn intensity. It was not every day they had the opportunity to inform the wife of a spy that her husband had been shot. They were all eyes: would she faint or not?

Svetlana was living through a totally surreal moment. She knew nothing. She did not know the trial was over, and she did not know that, convicted of high treason, her husband had been sentenced to death. During their last visit, Vetrov clearly had wanted to spare her, saying he still had two hopes: the KGB setup and his plea for clemency. The latter was denied on January 14, 1985. No one thought of officially informing his wife to prepare her for the inevitable. Vetrov had not been allowed to say his farewells to his family.

Despite her shock, Svetlana could think about only one thing: “They are waiting for me to faint.” She would not give them this satisfaction.

Like a sleepwalker, she left the office, went down the stairs, and found herself in the street. She sat on a bench to breathe and collect herself. Then she walked back home, straight ahead, less than half an hour away. The news sank in only later that evening. She had a violent spell of despair. Fortunately, she was home alone. She told no one. Vladik was to learn about his father’s execution two months later.

Svetlana had to struggle a little longer in this Kafkaesque universe. She had been told to go get her husband’s death certificate at her district registry office.

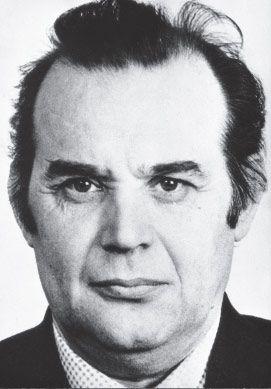

Vetrov’s last photograph shot in Lefortovo. The KGB hoped to launch a deception operation. Vetrov’s expression is striking. The uncovered spy must have had no illusions left about what was in store for him.

“We don’t have anything, go somewhere else!” answered a grouchy woman, deformed by obesity as is often encountered in Soviet administrations.

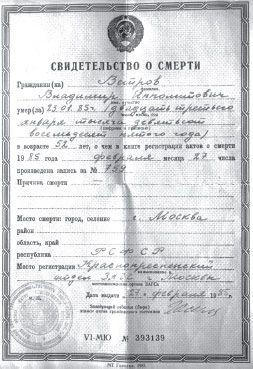

At the central office, it took a woman, who could have been her double, a good fifteen minutes of foraging through papers. She put Vetrov’s death certificate on the counter in front of Svetlana (

see Figure 8

). It was an ordinary form, showing a long dash in the space provided to indicate the reason of death. It was almost compassionate when you think what it would mean to go through all the necessary procedures having to indicate instead “shot by firing squad”!

Because of the strangeness of the situation, Svetlana thought for a long time that maybe Vladimir was still alive. Ten years later, she listened with great interest when Sergei Kostin told her that in France the rumor had it that, a KGB lure, Vetrov had undergone cosmetic surgery and was living in Leningrad, where Svetlana joined him every weekend.

7

Rumors of that nature could not be stopped since no one had seen the corpse. The next of kin never had this privilege.

This being said, as it sometimes happens, such rumors are not totally unfounded. Anatoly Filatov, for instance, a former GRU officer sentenced to death, was executed in 1978—or so they thought. Following his appeal to the Supreme Court, his sentence had been commuted to fifteen years’ imprisonment. Filatov was released in 1993. Likewise, a certain Pavlov from Leningrad, who was supposed to have been shot in 1983, ended up later in the famous camp #389/35 in Perm, and he was pardoned after serving ten years. This was certainly not Vetrov’s case; we would have found out by now. So how did Vetrov die? As with any other taboo subject, the execution of criminals creates a whole mythology.

Figure 8. Vetrov’s death certificate. A long dash is all there is to indicate the cause of death.

Some say that convicts sentenced to death were executed without advance notice, out of pity. The convicts already knew that their appeal had been rejected, and they were waiting in anguish for the moment they would be taken away. It did not happen at dawn, as in romantic popular novels. The convict, people say, was summoned to step out of his cell and, as usual, marched in front of his guard, executing orders to turn left, turn right, or stop. As he was entering a dead-end section of the basement, he was shot in the back of the head with no warning.

Others claim that, on the contrary, the convict was placed with his back to the wall in a large basement room with no windows, facing a firing squad. The squad was comprised of rank-and-file internal troops. They all targeted the convict’s heart, but out of eight cartridges, only three were live. Thus, none of the soldiers knew who fired the fatal shots.

According to still others, each “executing” prison, and there were only five of those in the entire Soviet Union, had one or two executioners who accomplished the task either from personal conviction or from inclination. These three approaches were probably all used at one time or another, hence the differences.

With regime change and the opening of some archives, the access gained to certain documents in recent years shed some light on this previously gray area.

8

Actually, each of the five “executing” prisons was served by a special operational unit, usually comprised of six men. They were detectives with, generally, other official functions in the Criminal Investigation Department. They met only two, three, or four times a month, in the utmost secrecy. Besides them and the regional head of the Ministry of the Interior, no one else had a clue about those missions. The unit met the convict in an area of the prison reserved for them, and then they conveyed him to a facility fitted out specifically for them, the existence of which was known by very few people. Sometimes, in order to avoid harrowing scenes, they told the convict some story justifying his transfer.

Once in the facility, which could indeed be a basement, a prosecutor, always the same, and always acting secretly, informed the convict that his appeal had been rejected and that the sentence was going to be executed shortly. Two detectives, numbers three and four in the unit, then grabbed the convict under the arms—at that moment the convict’s legs often gave way beneath him—and a third one, number one in the unit, fired one or two bullets in his head, almost at point-blank range. Each unit did their best to protect the three men from being spattered by blood and brain fragments. Authorities, however, made a point not to humiliate the convict during the final moments of his life. Thus, they dissolved a special unit who forced the convict to kneel down over a barrel filled with sand, a method deemed degrading.