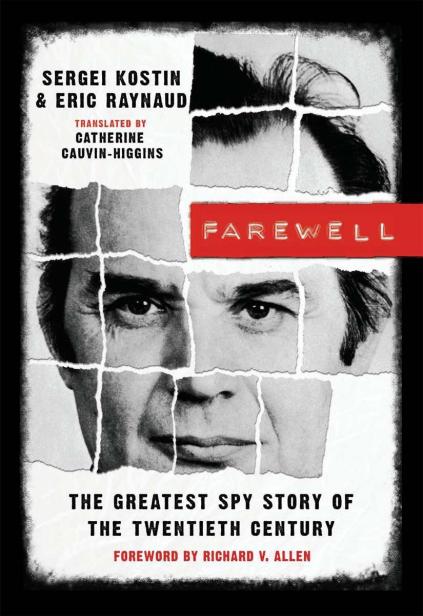

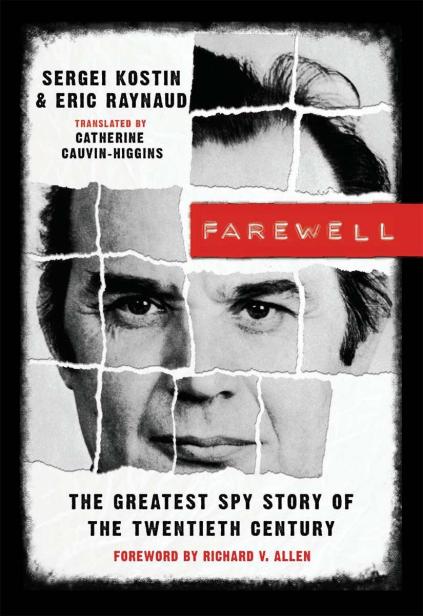

Farewell

Authors: Sergei Kostin

THE GREATEST SPY STORY OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

TRANSLATED BY

CATHERINE CAUVIN-HIGGINS

FOREWORD BY RICHARD V. ALLEN

Text copyright © 2009 Éditions Robert Laffont, S.A., Paris

English translation copyright © 2011 by Amazon Content Services LLC

Foreword copyright © 2011 by Richard V. Allen

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Farewell: The Greatest Spy Story of the Twentieth Century

by Sergei Kostin and Eric Raynaud is the English translation of their book

Adieu Farewell,

published in 2009 by Éditions Robert Laffont in Paris. The first version of this book, by Sergei Kostin, was published in 1997 by Éditions Robert Laffont in Paris as

Bonjour Farewell

.

Translated from the French by Catherine Cauvin-Higgins.

First published in English in 2011 by AmazonCrossing.

Published by AmazonCrossing

P.O. Box 400818

Las Vegas, NV 89140

ISBN: 978-1-61109-026-0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011900156

In 1976, five years before the Farewell case, Ronald Reagan nearly unseated President Gerald Ford for the Republican presidential nomination. The major salient of his attack on Ford was on foreign and national security policy. Reagan rejected “détente,” not because he opposed a relaxation of tensions with the Soviet Union, but because under Nixon, Ford, and Kissinger “détente” had taken on a special, nearly theological meaning—a supposedly ineluctable process of gradually making the Soviets completely dependent on trade and technology from the West, hence causing them to moderate their behavior in terms of global expansion and military procurement. Reagan believed the theory to be defective and dangerous, even intellectually bankrupt.

Gerald Ford went on to lose to Jimmy Carter in November, and the change in administrations merely resulted in giving the Soviet Union even greater incentive to pursue an aggressive course in its relationship with the United States. Reagan hosted a highly effective daily radio show from 1975 through 1979, regularly launching reasoned critiques of U.S. policies that failed to exact penalties for bad behavior from the other side. His speeches on foreign policy and defense increasingly reflected this tone: U.S. policy was in effect

rewarding

aggressive international behavior.

Although his critics repeated the mantra that Reagan was “simplistic,” Reagan believed that simply “managing” the Cold War was a losing proposition. On the contrary, as he said to me in his Los Angeles study in early February 1977, just days after Jimmy Carter was inaugurated president, “There is a difference between being ‘simplistic’ and having simple answers to complex questions.” Then he said, “So, my theory of the Cold War is that we win and they lose. What do you think of that?”

By “winning,” he did not mean that the other side would lose everything in disgrace and ruin—but that one side, the U.S. and its allies, would clearly “win.” He also believed in working to liberate the peoples of Eastern Europe and divided Germany suffering under the Soviet yoke. He meant what he said on that occasion; I waited many years before revealing his observation about “winning and losing.”

Reagan then developed a series of persuasive political arguments concerning future U.S. policy. I was privileged to be along for the years of journey to the election in 1980 and into the White House, serving first as his chief foreign policy adviser and then as his first national security adviser.

Surviving an assassination attempt on March 30, 1981, Reagan appealed to Leonid Brezhnev to sit down and negotiate critical issues contributing to tensions. The appeal was summarily rejected by Brezhnev.

In early May, less than four months into the Reagan administration, France’s François Mitterrand surprised everyone by unseating President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. The French Communist Party had supported Mitterrand, and the winner appointed four communist ministers to his cabinet. The State Department and U.S. press were in a state of shock, and my colleague, Secretary of State Alexander Haig, a close friend of D’Estaing, declined to brief the press. I had studied Mitterrand’s career for years, and thus it fell to me to brief the press as an “anonymous senior White House official.” The theme used in the briefing: Mitterrand would be a canny manager of his cabinet, and there was no need for negative reactions.

At the seventh G7 economic summit conference, July 20–21, 1981 at Chateau Montebello in Quebec, Mitterrand and Reagan met for the first time. Reagan was confident that he and the new French president would get along well; he was not mistaken.

After the formal meetings, Mitterrand met with Reagan very privately. Accompanying Mitterrand was Jacques Attali, his brilliant adviser whom he treated like a son, and I accompanied Reagan. Mitterrand revealed that France had a private sector company, Thomson-CSF, working on contracts in Moscow, and through it French intelligence had achieved a very deep penetration of the KGB. It had in place a key Soviet source who was voluntarily providing astonishing national security information about Soviet technology acquisition from the West, including massive theft of technological secrets. Thus was revealed the famous “Line X” KGB espionage network by one of the most precious and extraordinary “moles” the West ever had. The “Farewell” case was born.

Management of the matter in Washington was by Reagan’s close friend and mine, William J. Casey, CIA chief. On my National Security Council staff, an extraordinary fellow, Dr. Gus W. Weiss, whom I had first met in 1968 and then recruited for the White House international economic policy staff in 1971 in the Nixon administration and again in 1981 at the outset of the Reagan administration for the NSC, was given the assignment to handle and exploit this valuable intelligence resource from the White House end. The agent-in-place performed heroically, but committed actions that compromised his identity. The highly effective and secret cooperation served to reinforce French-U.S. relations and build mutual confidence.

The reader of this wonderful book by Sergei Kostin and Eric Raynaud is in for a treat: an introduction to what President Reagan described as the most significant spy story of the last century. Catherine Cauvin-Higgins, interpreter for the Thomson chief at the time, has performed a great service in translating the volume, expanded and updated with newly available information, including a Weiss memo published by the CIA, “The Farewell Dossier: Duping the Soviets.”

And expertly duped they were, principally by sophisticated economic warfare expertly waged. But to reveal more here would affect the reader’s exciting voyage into the murky world of espionage and counterespionage.

Just as Reagan had hoped and planned, one side actually “won.”